Book Review: Sisterhood of the Lost Cause: Confederate Widows in the New South

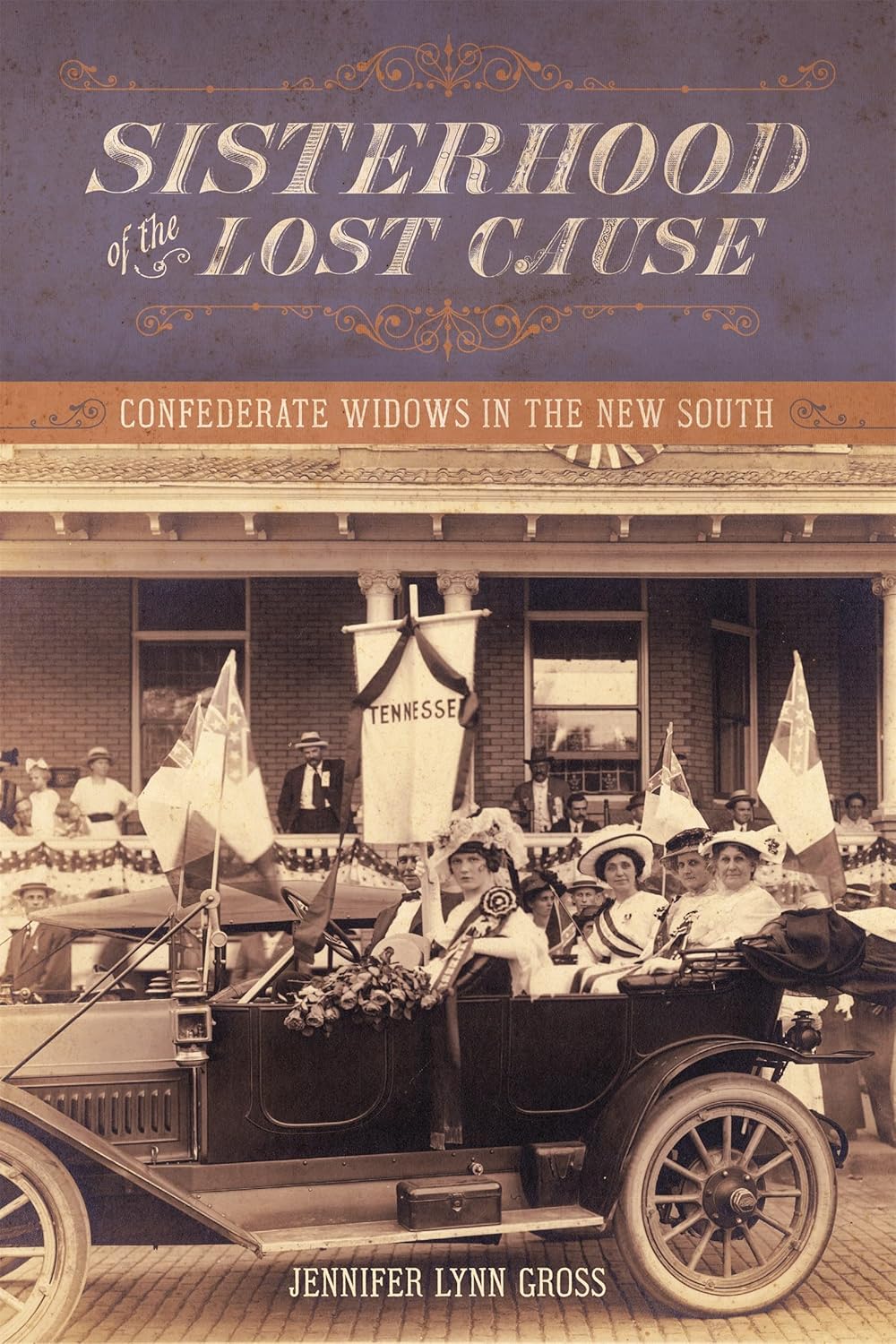

Sisterhood of the Lost Cause: Confederate Widows in the New South. By Jennifer Lynn Gross. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2025. Hardcover, 320 pp. $50.00.

Sisterhood of the Lost Cause: Confederate Widows in the New South. By Jennifer Lynn Gross. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2025. Hardcover, 320 pp. $50.00.

Reviewed by James Hill “Trae” Welborn III

While historian Jennifer Lynn Gross may not be the first to lift the proverbial veil through historical analysis of Confederate widows in the Civil War Era, her work significantly broadens and deepens the scope and scale of analysis on this pivotal subset during this crucial period in the history of the American South. Deploying a broad definition of Confederate widowhood that includes those widowed during the American Civil War as well as those widowed following postwar marriages to Confederate veterans, Gross traces the complex and evolving experiences of white, southern, Confederate widowhood and its equally dynamic and shifting social status and impact in the region from the beginning of the war through the first two decades of the twentieth century. Gross convincingly shows how Confederate widows reconciled their tenuous and contentious place as white “manless women” in a persistently patriarchal and white supremacist society by both adhering to patriarchal norms and challenging them in their prominent role as sustainers of wartime nationalism and stewards of memorial, commemorative, and celebratory “Lost Cause” cultural memory narratives across multiple generations of the postwar period. In addressing “how the existence of so many widows figured into the reconstruction of racial, gender, and class structures within southern society,” Gross successfully accomplishes her stated goal “to understand how the South rebuilt itself after its military defeat” and “sheds new light on the history of the Lost Cause and its role in the ‘New South.’” (12)

Gross divides the book into two parts, with the first exploring “the myriad experiences of Confederate widowhood for the widows themselves, with the primary focus on women who lost their husbands during the war or shortly thereafter.” (11) Chapter one analyzes how Confederate widows individually and collectively navigated the emotional (loss, grief) and cultural (adherence to gendered ideals as manifested in established mourning rituals) travails to become “symbols for the rest of the South, an emblem of their collective soul, rendering them mired in place as living representations of the desolation caused by the war.” (50) Chapter two then examines the diverse experiences of most Confederate widows for whom “their grief was accompanied by” tangible challenges (economic and social insecurity, physical privation) that “varied in intensity according to their financial situations, southern inheritance laws and practices, the presence or absence of children, opportunities for gainful employment [or prospects for remarriage], and a support system, or lack thereof, of helpful kin and friends.” (54)

Part two “shifts attention outward to how other southerners perceived Confederate widows and their plight” and “examines how white southern society came to terms with this new class of women, eventually re-ensconcing them within an ideological home… rhetorically through poetry, literature, and memorial activities; and practically through the benevolence of postwar Confederate associations and the distribution of pensions.” These, Gross argues, “combined to create the collective imagination that Confederate widows were willing martyrs for the Lost Cause who not only belonged within the fold of proper southern womanhood but also were its ideal.” (11-12) Chapter three focuses on Confederate widows both as subjects of postwar poetry and literature and as authors of said verse and prose. Chapter four analyzes Confederate widows’ essential roles in Confederate memorialization as essential symbols of ideal “white southern womanhood for their assumed gracious abnegation and thus glorious martyrdom–just as Confederate soldiers represented the ideal in white southern manhood. Within the Lost Cause, dead Confederates, living veterans, and Confederate widows were the ultimate icons, deserving of honor and respect as well as, when possible, benevolence.” (146) Gross’s final chapter focuses on the ways that former Confederate state governments, when controlled by white southern Democrats during Presidential Reconstruction immediately after the war and again following the demise of Congressional Reconstruction from the late 1870s onward, rewarded Confederate widows through state-funded pensions, the purpose of which Gross sees as two-fold in fulfilling “the very practical need of providing for indigent southern veterans and widows” while also serving “the ideological need of buttressing traditional southern patriarchy.” (215)

Gross engages a broad yet deep and rich primary source base that includes a bevy of organizational and government records as well as the personal papers of dozens of Confederate widows in archival collections. Her analysis of these hyper-personal stories within the broader context of these regional heritage organizations and state government agencies/policies is as impressive as it is seamless in both execution and insights provided. As such her work brings together various strands of historical scholarship by centering Confederate widows within the larger context of the Civil War Era and the immense transformations it wrought in American society and culture across the nineteenth century and in American cultural memory since. Gross acknowledges especially Drew Gilpin Faust’s work (This Republic of Suffering) on the shifting conceptions of and rituals associated with death during the Civil War Era and its pertinence to widows’ experiences and public image while also extending the insights of Civil War Era gender historians such as Catherine Clinton, Nina Silber, and LeeAnn Whites in her analysis of Confederate widows within these larger gendered frameworks and contexts. Gross most directly engages the work of other scholars of Confederate widowhood, including Elna Green (Before the New Deal and This Business of Relief), Marie Malloy (Single, White, Slaveholding Women in the Nineteenth-Century South), and especially Angela Esco Elder (Love & Duty: Confederate Widows and the Emotional Politics of Loss), providing a broader, more comprehensive framework within which the subjects analyzed by these scholars can be understood more holistically. Gross’s work therefore bridges a gap between the wartime and Reconstruction experiences of, and developments related to Confederate widows and their impact on Civil War memory narratives, especially as analyzed by historians Karen Cox and Caroline Janney, who emphasize the crucial role of women in creating and sustaining the Lost Cause mythology.

Thoroughly researched and conveyed in clear, lively prose, Sisterhood of the Lost Cause will be essential reading for scholars seeking to more fully understand the experiences of Confederate widows and their place in southern society during the Civil War Era while remaining accessible for a more general audience interested in the Civil War Era and its continually evolving memories and legacies.

Dr. James “Trae” Welborn is Assistant Professor of History at Georgia College & State University in Milledgeville, Georgia. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, reared in Fernandina Beach, Florida, and educated at Clemson University and the University of Georgia, Dr. Welborn specializes in American cultural history, with an emphasis on the emotional dimensions of evolving conceptions of virtue, vice, and the role of violence in shaping these cultural values during the American Civil War Era. The University of Virginia Press published his book, Dueling Cultures, Damnable Legacies: Southern Violence and White Supremacy in the Civil War Era, in 2023.

I wonder (rhetorically) – Did White Supremacy exist in the North, or only in the South?

What does that question have to do with the book or the review?

I believe Mr. Schafer is merely taking notice of one of the elephants in the room: WHITE widows of the South… leaves out Hispanic widows and mixed-race widows… not to mention Black widows. This elephant holds tightly to the tail of another elephant: race relations after the Civil War concluded.

If we accept that “Reconstruction was a failure,” then the elements that worked to achieve that failure were: the KKK; lack of Northern will, bordering on complicity with Southern Lost Cause (and White Supremacy) interests; the UCV and its political power; the UDC and its political power [UDC membership doubtless included many widows.]

For me, the statement of the reviewer that nudged me offside was “Gross’s work therefore bridges a gap between the wartime and Reconstruction experiences of, and developments related to Confederate widows and their impact on Civil War memory narratives…” Because it is my contention that Southern Civil War Memory and Southern memory communities are modern constructs, put forward as justification – not merely explanation – of unsavoury actions and re-remembered outcomes of the past, a.k.a. My Truth, as opposed to The Truth.