The Forgotten Stand of Sweitzer’s Brigade in Gettysburg’s Wheatfield

“There goes the Second Brigade; we may as well bid it good-bye,” remarked Brig. Gen. James Barnes as the men of Col. Jacob Sweitzer’s brigade entered the Wheatfield at Gettysburg for the second time on July 2, 1863. The Second Brigade, First Division, of the V Army Corps had seen its fair share of bloodletting in the Civil War thus far, but its stand in the Wheatfield surpassed most of it.

The brigade consisted of four veteran regiments (the 62nd Pennsylvania, 4th Michigan, and the 9th and 32nd Massachusetts) and saw its first fighting during the Seven Days Battles of 1862. First under the command of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin, the Second Brigade suffered heavy casualties at Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill. After participating briefly in the battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, the brigade found itself in the capable hands of Col. Jacob Bowman Sweitzer, a Brownsville, Pennsylvania native and a lawyer by trade.[1] Sweitzer assumed leadership of the Second Brigade at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville in the absence of Griffin, and he retained this command in June 1863 as the Union army marched toward Gettysburg.[2]

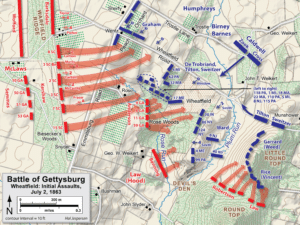

On the afternoon of July 2, Sweitzer and his brigade found themselves in reserve along with the rest of the V Corps. However, by late afternoon, Sweitzer and his men could hear Confederate cannons on the Union left. Brigadier General James Barnes rapidly moved his first division into the Wheatfield to support Gen. Daniel Sickles’s weak and fractured III Corps line, which had stretched well beyond its means. With Col. Strong Vincent’s Third Brigade marching off to glory on Little Round Top, Barnes only had practical command of Sweitzer’s Second Brigade and Col. William S. Tilton’s First Brigade.

Barnes’s men deployed haphazardly around the Stony Hill, adjacent to the Wheatfield and the home of its owner, George Rose. Tilton’s brigade formed a line of battle first while Sweitzer’s brigade filed in behind them. With the 9th Massachusetts detached on picket duty, Col. Sweitzer had only three regiments at his disposal. He formed his brigade in a right angle, with the 4th Michigan and 62nd Pennsylvania facing west toward the Peach Orchard and the 32nd Massachusetts facing south.

The Confederates struck soon after the brigade’s arrival; men from Georgia swarmed out of the Rose Woods to the south. Tilton’s men met the enemy first, then the 32nd Massachusetts joined the fray with a steady volley. “The men received the fire of the enemy with great coolness,” recalled one Bay-Stater, and he asserted that the regiment returned fire “with spirit and success.”[3] The exchange of musketry was so fierce that a soldier of Tilton’s brigade remembered hearing the Rose family’s dinner bell ring every time a bullet struck it.[4]

As Tilton’s men wavered, Sweitzer shuffled the 62nd Pennsylvania and 4th Michigan to meet the advancing Georgians. Both regiments shifted from their position facing west and filed in behind the 32nd Massachusetts. Having just repulsed Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson’s Georgians, Sweitzer’s men faced another threat. Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade came bearing down on the Stony Hill from the Peach Orchard to the west. With Tilton’s brigade in retreat, Sweitzer would be caught in a crossfire.

Barnes watched distantly as his two brigades faced jeopardy of being crushed, and he ordered Sweitzer to withdraw before it was too late. “General Barnes sent me word to fall back [. . .] which I did in perfect good order, the regiments retaining their alignments and halting and firing as they came back,” the colonel recalled.[5] Now resting in the shelter of Trostle’s Woods, Sweitzer and his men watched as the Confederates claimed the Stony Hill and the Wheatfield.

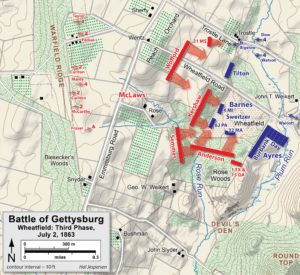

However, Union reinforcements were arriving. General Meade himself had ordered Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell’s division of the II Corps to reinforce Barnes in the Wheatfield. Sweitzer’s men watched as their comrades deployed in front of them and disappeared into the smoke. “We had not remained here more than, say, fifteen minutes,” Sweitzer recalled, “when a general officer I had never seen before rode up to me, and said his command was driving the enemy in the woods in front of the wheat-field; that he needed the support of a brigade, and desired to know if I would give him mine.”[6] It was Caldwell. His division had advanced through the field and now clung to a precarious position in the Rose Woods. Sweitzer agreed to help, but first requested permission from his direct superior, Gen. Barnes. With Barnes’s approval, the Second Brigade formed into line of battle and advanced in support of their II Corps comrades.

Sweitzer rode proudly in front of his three regiments as they marched back across the field of wheat. Colonel Harrison Jeffords’s 4th Michigan held the right, with Col. George Prescott’s 32nd Massachusetts on the left, while Lt. Col. James C. Hull’s 62nd Pennsylvania marched in the center. As their colors flapped in the wind, the men tried desperately not to trample over their own dead and wounded comrades that had fallen earlier in the fight. However, as they reached the southern edge of the field, the Second Brigade was greeted by unwelcome sights and sounds. The Michiganders could hear musketry atop the Stony Hill, now located behind them and to their right. Sweitzer initially believed this to be friendly fire, that men of Caldwell’s division were mistakenly shooting down on the Michiganders from the small hill, but he quickly learned the truth: they were Confederates. The brigade flag bearer, Pvt. Edward Martin, turned to Sweitzer and exclaimed, “I’ll be damned if I don’t think we are faced the wrong way; the rebs are up there in the woods behind us, on the right.”[7]

Indeed, Kershaw’s South Carolinians had reclaimed the Stony Hill, while Gen. William T. Wofford’s brigade of 1,350 Georgians was advancing down the Wheatfield Road. To make matters worse, Anderson’s Georgians, now joined by Gen. Paul Semmes’s brigade, were pushing Caldwell’s men back through the Rose Woods. Sweitzer’s brigade, initially intended as support, was now sacrificing itself to buy time for Caldwell’s division to escape. Responding to the newfound precarity of his position, Sweitzer refused his brigade line so that the 4th Michigan faced west toward the Stony Hill. Colonel Hull quickly wheeled the 62nd Pennsylvania right to follow suit.

There, the Second Brigade stood at a right angle to face the Confederates who outnumbered them nearly four to one. As the Rebels closed in, violent hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Colonel Jeffords was stabbed in the abdomen with a bayonet while trying to recover his regiment’s colors. The 62nd Pennsylvania’s color guard fought desperately with the cold steel to maintain possession of its flags. The national colors eventually fell to Confederate hands (only to be recaptured by Corp. Johnson C. Gardner), but Corp. Jacob Funk defended the state colors from a Rebel captor. Funk later wrote that one Confederate “leveled his gun and ordered me to surrender my colors or he would shoot me.” But the 21-year-old Fayette County native had other ideas. He turned and ran. “I took leg bail for security and increased the distance between him and me very fast,” Funk recalled. “I had to jump a stone fence and came very near losing my balance but I managed to get over. I then went straight ahead when I heard the report of a gun just behind me. I concluded that was for me, and sure enough the ball struck my arm.”[8]

As casualties began mounting, Sweitzer sent his aide-de-camp to inform Barnes of the brigade’s desperate stand—but no help came. By then, the colonel’s horse had been shot, and his hat had been pierced by a bullet. It was at that point Sweitzer knew his men had worn out their welcome, and he gave the order to fall back. “Finding, as we retired in the direction from which we advanced, that the fire of the enemy grew more severe on our right, I took a diagonal direction toward the corner of the wheat-field,” Sweitzer wrote in his official report.[9] The survivors hopped over a stone fence and rallied behind the safety of Wolcott’s Battery C, First Massachusetts Battery just north of Little Round Top.

Sweitzer’s brigade held the Wheatfield just long enough for Caldwell’s division to escape and bought time for additional Union reinforcements to arrive. As the Second Brigade limped off the field, they ceded it to Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres’s U.S. Regulars and Crawford’s Pennsylvania Reserves, both of whom launched counterattacks that ultimately stymied the Confederate momentum. When the smoke cleared and the sun had set, Sweitzer’s men had lost 466 men out of about 1,000.

While the Wheatfield fight lives in infamy as one of the costliest at Gettysburg, the stand of Sweitzer’s men is largely overshadowed by the actions of Caldwell’s division and other units. However, the Second Brigade’s act of bravery bought time for Caldwell’s men to retreat and Ayres’s Regulars to launch a counterattack against the Confederate onslaught. The brigade went on to participate in some of the war’s bloodiest fighting during the Overland Campaign and in the Siege of Petersburg, but they never forgot their desperation in Gettysburg’s Wheatfield.

Notes:

[1] Samuel Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, (B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869), 454.

[2] “Gen. J.B. Sweitzer Dead,” Pittsburgh Press, Nov. 9, 1888; Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 454.

[3] Francis J. Parker, The Story of the Thirty-Second Regiment Massachusetts Infantry, (C.W. Walkins & Co., Publishers, 1880), 170.

[4] John Lord Parker, Henry Wilson’s Regiment: History of the Twenty-Second Massachusetts Infantry, the Second Company Sharpshooters, and the Third Light Battery, in the War of the Rebellion (Butternut and Blue, 1996), 334.

[5] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 611.

[6] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 611.

[7] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 612; Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day, 291.

[8] Matt Masich, “The ‘War History’ of Corporal Funk.” Pennsylvania Legacies 13, no. 1–2 (2013): 66–75.

[9] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 612.

Thanks for highlighting this action in the Wheatfield! An interesting account…

Thank you for writing this description of western Pennsylvania’s bravest. It must have been difficult for the men of the 62nd PA to have been ordered to fall back from Stony Hill. I have read that many men initially resisted, but complied. There also may have been a moment in that 15 minutes on the Wheatfield Road that Sweitzer’s men were passed by the 140th PA of Zook’s Brigade of Caldwell’s Division. Both of these were western PA units. Excellent article

For sure. It seems that Sweitzer’s brigade were taking cover in the Wheatfield Road, as the 140th PA passed over them. Members of Zook’s brigade remember “stepping over” other Union troops belonging to the V Corps.

My favorite section of the battlefield, and frankly, given all the charges and counter charges, the most confusing! Excellent post.

Thanks, John. That means a lot coming from you! I agree, it’s one of my favorite sections of the battlefield as well.

The monument of the 4th Michigan and the story of its colonel holding the flag are moving. Evan does a great job of sequencing the action here-not an easy task.

Thanks, GrandadPookers!