Just War Theory and the American Civil War

ECW welcomes back guest author Ed Lowe.

Those familiar with Just War Theory may rightly point back to Saint Augustine (354-430) or Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) as the driving force behind its organization and application. Cicero and early Church fathers had already addressed some of the principles that would guide this doctrine for centuries to come. Shaped by Augustine and Aquinas, these doctrines would not only seek means to avoid conflict but also prescribe practices and guidelines during times of conflict.[1]

Students of this theory may identify its three key principles: Jus ad bellum (the morality of going to war), Jus in bello (the morality of fighting it), and Jus post bellum (the morality of ending it). The key elements of Jus ad Bellum include legitimate authority, just cause, right intention, likelihood of success, proportionality of ends, and last resort. For Jus in Bello, these include military necessity, proportionality, and discrimination. Order, justice, and conciliation make up the principles under Jus Post Bellum.

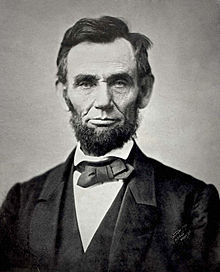

In his magnum opus, City of God, Augustine wrote, “For every man seeks peace by waging war, but no man seeks war by making peace.”[2] Therefore, no matter how brutal the fighting, punishment, and the correction of wrongdoings are critical so that “peace may follow.” Augustine’s penalty of wrongdoers and lawbreakers is, to a large degree, a way of “loving one’s neighbor.”[3] President Abraham Lincoln consistently valued this approach when it came to his policies toward the Southern population. They were rebellious, yes, but “neighbors” to be brought back into the family of the United States upon the cessation of arms.[4]

In Aquinas’s view, warfare was intended either for “the advancement of good, or the avoidance of evil.”[5] He identified three main requirements for initiating a conflict. First, the decision comes from a legitimate and sovereign authority. Second, the cause must be just. Lastly, the sovereign electing must have the right intention.[6] One could argue that Lincoln possessed all three of Aquinas’s elements for the upcoming hostilities. While critics might claim that Lincoln “had maneuvered the South into beginning the war,” what Lincoln did was to remain faithful to his inaugural pledge: to grip tightly those properties belonging to the Federal government. Lincoln sought to avoid conflict and prevent the nation from plunging into violence. Lincoln would approach the growing storms of discord with both a just cause and the right intention.[7]

Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson Davis had differing views on cause and intention. For the South, abolitionist influences, Northern state laws, and court decisions led South Carolina to state in its secession convention, “the constituted compact had been deliberately broken and disregarded by the non-slaveholding states.”[8] Lincoln, confident that he could not influence slavery before hostilities started, was firm that for the Union, “perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments.” Congress could pass legislation or call for a Constitutional convention to address a state’s right to secede. Otherwise, Lincoln remained steadfast in his beliefs.[9]

This played out when James Buchanan, the president before Lincoln assumed office, allowed the first seven states to leave the Union. While Buchanan may not have believed in the states’ right to secede, he felt the Federal government could not forcibly bring the states back into the Union. These Constitutional issues demonstrate the sheer complexity of Jus ad Bellum concerning the Confederate States.[10] Of course, the issue of slavery slams any Southern argument for just cause and right intention from almost every angle; it is challenging to mount a vigorous defense when coming face to face with that reality. Davis, however, wrote that the Confederate States and the South were “for the defense of an inherent, unalienable right.” As far as Lincoln and his policies, it was, to Davis, simply “one of aggression and usurpation.”[11]

After assuming office, Lincoln “agonized over the crisis’s critical decision until the last possible moment.” Lincoln gave the Northern population assurance that he was doing all he could to resolve the growing tension without resorting to armed conflict: The application of last resort was on full display. Lincoln’s efforts in the weeks before the firing on Fort Sumter enabled the North to recognize “who was truly at fault.” Lincoln could fully appropriate the elements found in Jus ad Bellum.[12]

Southerners could exclaim that states’ rights, vehement Northern abolitionist statements, and/or failure of the U.S. government to enforce the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act provided a just cause to secede. Consequently, such a cause would invariably initiate a formal conflict, given Lincoln’s position on the issue. Moreover, the defense of the Antebellum lifestyle and the institution of slavery itself could be viewed by the Richmond authorities as delivering the right intention.[13] One could argue whether the Confederate government in Richmond even had legitimate authority to take the actions it did. Nevertheless, the opinion that the Constitution set forth a national government rather than an agreement of sovereign states was “simply false” to Jefferson Davis.[14]

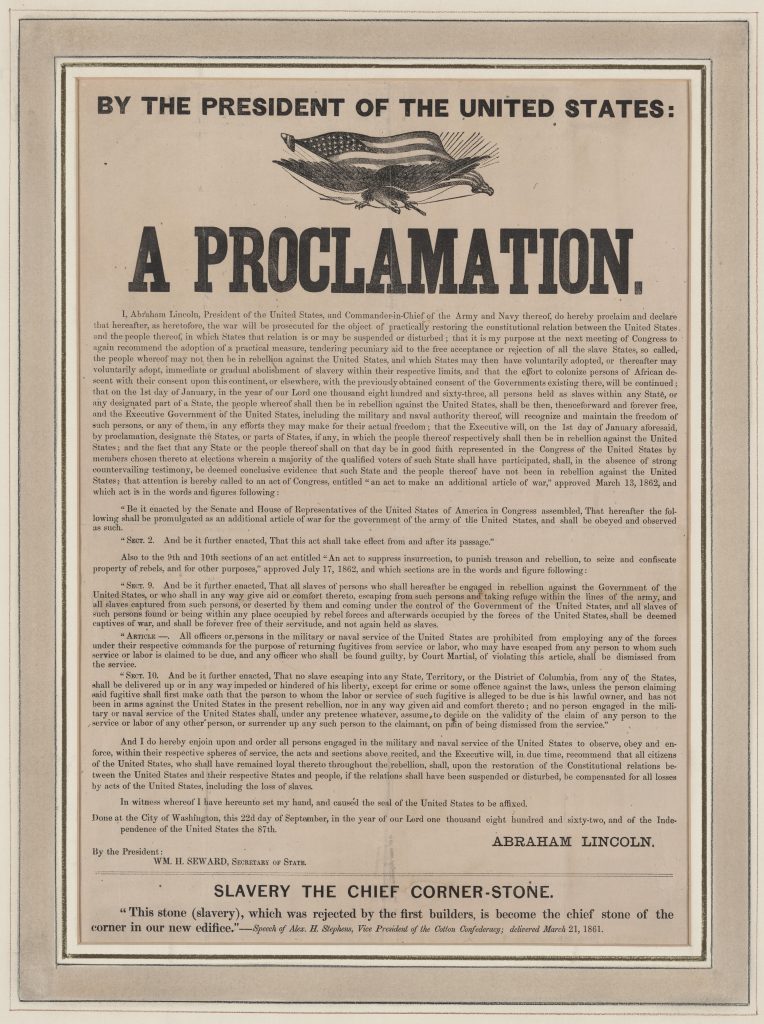

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation turned the debate of authority and freedom on its head. In Europe, Southern commissioners and diplomats peppered these nations, particularly Britain and France, with the claim that their fight was about freedom. Britain and France disliked slavery, which served as a cause for not intervening. However, in the end, “the cost of intervention was steep and promised little in return except for the chance to buy Southern cotton.” Showing favor to the North, France saw a “strong American republic as a check on British power.” The self-interests and Realpolitik of European nations were on exhibition.[15]

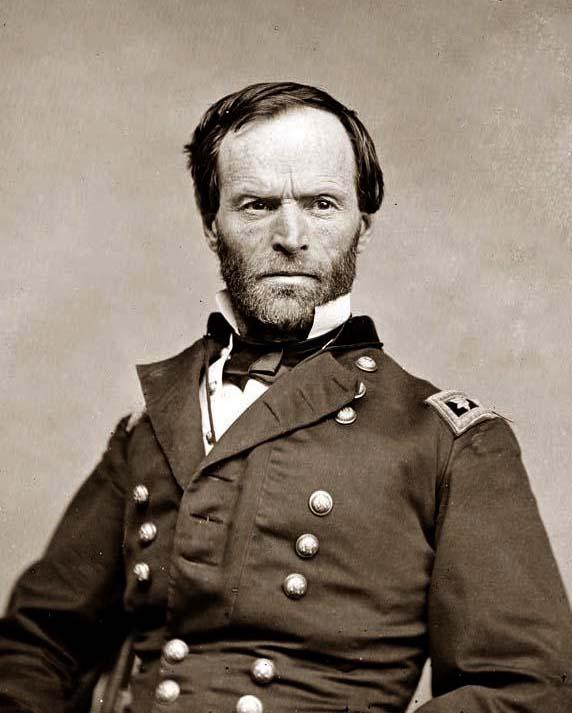

For Jus in Bello, William T. Sherman’s movement through Georgia in 1864 can evoke strong emotions in today’s history circles. Grant’s directive to Sherman was to “[inflict] all the damage you can against their war resource.”[16] Aside from the military resources that Atlanta could offer, the political component proved just as vital. As historian David Powell points out, the fall of Atlanta “was a tremendous blow to Southern spirits; to the North, it was seen as a confirmation of Lincoln’s strategy.”[17] Nonetheless, the elements of proportionality and discrimination under Jus in Bello can be questioned regarding Sherman’s actions in and around Atlanta and his advance on Savannah. Proportionality means that the tactics used closely align with the objectives pursued on the battlefield. With discrimination, are distinctions made to protect the lives and property of noncombatants? Albert Castel bluntly stated, “The depopulation of Atlanta is the harshest measure taken against civilians by Union authorities during the entire Civil War.”[18]

Sherman’s operations in South Carolina also raise questions about proportionality, discrimination, and what constitutes military necessity, perhaps more so than those in Atlanta.

This also introduces another element of the theory, which is Double-Effect. With this, the actor’s intention is noble and good, and the perceived evil is neither an end nor a means to that end. As Michael Walzer underscored, “The good effect is sufficiently good to compensate for allowing the evil effect.” Arguably, Sherman’s actions in Georgia and South Carolina exemplify the principle of double-effect.[19]

With Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, the elements of order, justice, and conciliation in Jus post Bellum would prove instrumental to the conflict’s end and into Reconstruction, according to Lincoln. At Appomattox, when Lee surrendered his army, Grant magnified Lincoln’s wishes. “The people who had been in rebellion must necessarily come back into the Union,” Grant emphasized, “and be incorporated as an integral part of the nation…they surely would not make good citizens if they felt that they had a yoke around their necks.” Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas would have applauded Lincoln’s efforts to offer a peaceful return to the Union.[20]

The principles of Just War Theory have evolved over the centuries and continue to do so today. The application of Jus ad Bellum, Jus in Bello, and Jus post Bellum can still provide sound direction and guidance to leaders, both politically and militarily, in today’s world. The complexities of America’s Civil War are not limited to its combat but also to its causes. As the morality of fighting has been a concern for armies for centuries, America’s internal conflict was no different. Yet, President Lincoln stayed true to his course. And those famous words from his second inaugural in March 1865 demonstrated his conviction, “With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan ~ to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Words that Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas would undoubtedly have celebrated.[21]

COL (ret) Ed Lowe served 26 years on active duty in the U.S. Army with deployments to Operation Desert Shield/Storm, Haiti, Afghanistan (2002 & 2011), and Iraq (2008). He attended North Georgia College and has graduate degrees from California State University, U.S. Army War College, U.S. Command Camp; General Staff College, and Webster’s University. He is married with two daughters and lives in Ooltewah, Tennessee.

Endnotes:

[1] Henrik Syse & Gregory M. Reichberg, ed., Ethics, Nationalism, and Just War: Medieval and Contemporary Practices (Washington, DC, 2007), 36, 43.

[2] Saint Augustine, City of God, 19.12, vol. 3. Philip Schaff, eds., (New York: 1886).

[3] Syse & Reichberg, Ethics, 37, 40.

[4] Eric Patterson, A Basic Guide to the Just War Tradition (Grand Rapids, MI, 2023), 43-45.

[5] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II, 2nd ed., trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (London, 1920-1935), 40.

[6] Patterson, A Basic Guide, 47.

[7] Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals (New York, 2005), 346.

[8] Paul Finkelman, “Slavery, the Constitution, and the Origins of the Civil War.” OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 14-18.

[9] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address-Final Text” Collected Works (New Brunswick, 1953), 4:264-265.

[10] ; “Confederate States of America and the Legal Right to Secede,” found at https://www.historyonthenet.com/confederate-states-america-2, accessed May 30, 2025.

[11] Jefferson Davis, The Fall of the Confederate Government, reprint (New York, 2010), 703.

[12] Russell McClintock, Lincoln and the decision for war, (Chapel Hill, NC, 2008), 253.

[13] Finkelman, “Slavery, the Constitution, and the Origins of the Civil War.” pp. 14-18.

[14] Han Liu, “Three Arguments of the ‘Right to Secession’ in the Civil War: International Perspectives,” 41 HASTINGS INT’L & COMP. L. Rev. 53 (2018), 75.

[15] Donald Stoker, The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War. (New York, 2010), 30-31.

[16] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, (New York, 1988), 722-723.

[17] David Powell, The Atlanta Campaign, 1864: Peachtree Creek to the Fall of the City. (Havertown, PA, 2024), 121.

[18] Albert Castel, Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864. (Lawrence, KS, 1992), 549.

[19] Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars: A moral argument with historical illustrations. (New York, 1977), 153.

[20] Brian Thomsen, ed., The Civil War Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (New York, 2002), 485.

[21] Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. Found at https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-second-inaugural.htm, accessed May 28, 2025.

The Emancipation Proclamation, ironically heralded as “Lincoln freeing the slaves,” not only did no such thing, but made clear that the war was to put down the rebellion, not end slavery. It states that only such slaves in those states or territories rebelling against the Union would be free, making it clear that if a state or territory stopped rebelling against the Federal Government, they could keep their slaves…as did the handful of slave states that remained in the Union – and the Government protected their slave-holding rights. True to his word, five months after the Proclamation’s issuance, Lincoln welcomed West Virginia into the Union – as a slave state.

Great points there. Thank you. Ed

My comments are not directed to Mr. Ed Lowe personally. I am sure he is a fine man who is only writing what he has been taught by his professors. Implying that Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman were heroes, upholders of the law, who complied with the rules of war, is simply not true. Lincoln violated the Constitution frequently, such as eliminating the rights of his own northern citizens. Putting northern newspaper editors in jail with no due process because they dared to write editorials negative to him is just one example. Most historians today detest the term “revisionist history.” In fact, a lot of what they write is true. They just leave out all the facts which do not support their position.

I am 78 years old now. I earned three university degrees, am a published Civil War history author, and a life long student of American history. That, and $9 can buy you a good cup of coffee at Starbucks. But, I was born and reared in the Lowcountry of South Carolina which Sherman “encouraged” his troops to destroy. All of you know this is true, but you continue to support the North’s “Righteous Cause Myth.” Most of today’s Ph.D. historians are writing what they were taught by their leftist liberal professors who teach what their left liberal professors taught them, etc. I support “Emerging Civil War” and often refer to your authors in writing my own Civil War History posts for my 16,000 followers.

I know what I think and write does not amount to a “hill of beans.” But, sometimes, I just can’t help myself. I don’t expect you to post this, and I wish for all of you much Grace and Peace.

Can you tell me one illegal or unconstitutional action that you accuse the U.S. government of taking that was not also taken by Jeff Davis or the Army of Northern Virginia when it was on northern soil?

Although the question is irrelevant, the answers are not – murder, rape, grand theft, suppression of rights. If, as the Federal Government claimed, the South never left the Union and the Confederate States of America were still part of the United States of America, then the list of crimes committed by that Government against the Southern States runs into the tens of thousands. If the Confederate States were no longer part of the United States, then the list of crimes committed against them runs into the tens of thousands.

Mr. Schafer, thank you for your response, which is nonspecific at best, but I’m sure the original poster can speak for himself.

Mark, I understand your perspective. Thanks for your comments. I was not writing about the Confederacy. Of course, there were violations on both sides, but Jefferson Davis was not the President of the United States. My comments were not made to defend the Confederacy. They were made to tell the truth about Lincoln and especially Sherman.

Well said, Mr. Harvey. Spot on target.

How’s that book coming along?

Thank you, Jim, for your perspectives. My focus for this short piece was exclusively on Just War Theory and not any Constitutional issues that might have arisen throughout the war. I hope that clarifies the direction I was headed with this short piece. You made some good points, which may make it worthwhile to pursue for another ECW Blog article. Regards, Ed.

Thanks, Ed.

I always thought the victors get to determine who was, and who was not, “just” and “right” and “righteous” and all of the usual terms? “To the victor goes the spoils” and all that?