Book Review: Fighting for Freedom: Black Craftspeople and the Pursuit of Independence

Fighting for Freedom: Black Craftspeople and the Pursuit of Independence. Torren L. Gatson, Tiffany N. Momon, and William A. Strollo, Eds. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2025. Hardcover, 153 pp. $35.00.

Fighting for Freedom: Black Craftspeople and the Pursuit of Independence. Torren L. Gatson, Tiffany N. Momon, and William A. Strollo, Eds. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2025. Hardcover, 153 pp. $35.00.

Reviewed by Lucas R. Clawson

People of color produced a staggering amount of goods consumed by Americans from the 17th through 19th centuries. Some were free, most were enslaved, and practically all were overlooked or forgotten. Fighting for Freedom: Black Craftspeople and the Pursuit of Independence helps remedy this by pushing readers to think about all the things people of color made, the sorts of things they produced, and touching on the historiography of African-American made goods as objects of celebrated material culture.

Fighting for Freedom is a companion book to an exhibition of the same name held at the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum in Washington, D.C. The exhibition, held in collaboration with the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive (blackcraftspeople.org), “seeks to embrace the stories of all those who pursued independence by centering on the lives and experiences of Black craftspeople and artisans from the 18th and 19th centuries.”[1] The book is a series of essays by historians, museum curators, material culture scholars, and a current craftsperson that give context to the exhibition. The book also provides a catalog of items in the exhibit with full color photos and commentary on the objects.

Fighting for Freedom will leave readers with more questions than answers. Which, given the subject matter, is a good thing. The essays are short (between six and eight pages not counting endnotes) so there is only so much the authors can cover. This is a strength and definitely not a weakness because it leaves the reader wanting more. The rich bibliographic references that these essays provide point toward the large body of emerging scholarship on people of color as participants in the craft economy. Plus, drawing from a wide variety of primary source materials, both in terms of documentary sources and objects, it gives readers a starting point for more research.

One of this book’s strengths is helping redefine what is considered “craft” and what craftspeople do. We tend to think of joiners who make fine furniture or silversmiths or potters as craftspeople. But we often do not think of people like house painters, launderers, or those who make commonplace items like brooms or highchairs in the same light. Fighting for Freedom makes the argument that all of these people participated equally in craft production. Broadening the definition of craft deepens our understanding of craftspeople because it links them to practically all parts of the economy, not just luxury goods. This demonstrates the agency of Black craftspeople and how the very act of being a craftsperson could be an act of defiance. Rethinking what craft is and who craftspeople are serves readers lots of food for thought.

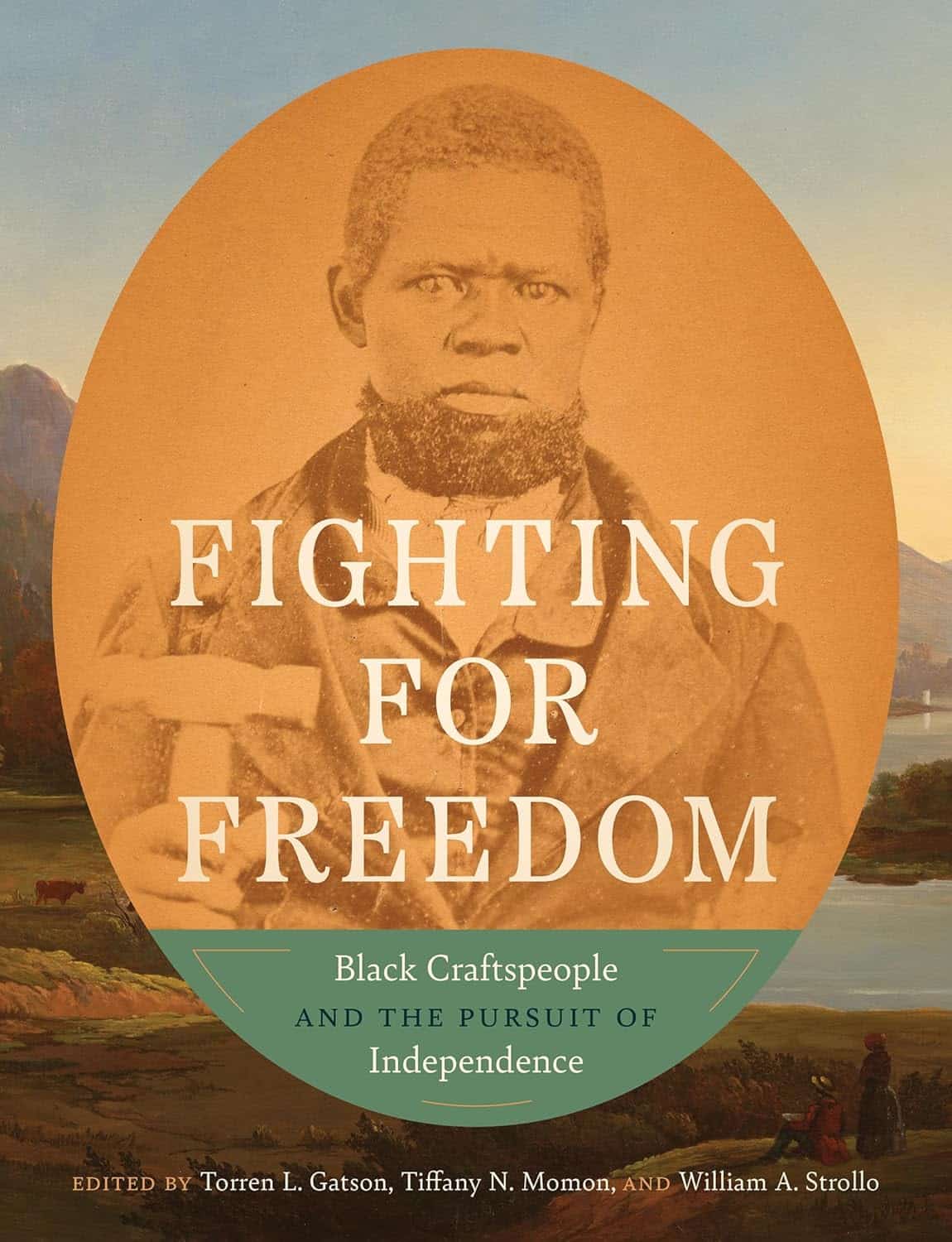

Fighting for Freedom includes high-quality color photos of people, objects, paintings, and documents. This includes both the contextual essays and the exhibition object catalog. All of the images beautifully illustrate the points the authors make, helping the reader understand the objects and the people who made them. The photos are just as important as the text, which is critical in a book that uses material culture to help make its argument.

One of the largest takeaways from this book is showing readers how embedded Black craftspeople were in America. They were part of the economy. There were part of communities. All were highly skilled in their particular trades. They participated in the everyday lives of all people, not just a particular class. It is easy to miss them if we are not looking, and for a very long time we did not look. Fighting for Freedom reminds us that Black craftspeople were there and that we need to pay attention. We live in a world of “stuff”, all of which has to come from somewhere. For a good portion of American history, as this book points out, that somewhere was Black craftspeople.

[1] https://www.dar.org/collections/exhibitions/fighting-freedom-black-craftspeople-and-pursuit-independence (Accessed July 30, 2025)

Lucas R. Clawson is an independent scholar based in Lebanon, Oregon. Lucas spent over two decades in the public history field, interpreting the Civil War and American industrial history. Lucas is currently owner of Clawson Woodworking, where he uses 18th and 19th century tools and techniques to make wooden items of all sorts.