The Autopsy of Philip Kearny

The Battle of Chantilly, fought during a thunderstorm on September 1, 1862, just 18 miles west of Washington, D.C., marked a brief but bloody end to the Second Manassas Campaign.

The day before, General Robert E. Lee had ordered General “Stonewall” Jackson to lead half of the Army of Northern Virginia on a flanking maneuver around Major General John Pope’s forces at Centreville, aiming to cut off the Union army from Washington. In response, Pope sent Brigadier General Isaac Stevens and his 9th Corps to strike the advancing Confederates and secure the Union line of retreat. Brigadier General Philip Kearny’s division supported Stevens.

In the short but intense clash that followed, about 500 Confederate and 700 Union soldiers were killed or wounded. Among the dead were Generals Stevens and Kearny. Amid the confusion of battle, Kearny rode forward to rally his men but mistakenly passed beyond Union lines into the ranks of the 49th Georgia Infantry. Realizing his error, he wheeled his horse around and tried to escape. A scattered volley rang out, and one bullet struck him from behind, passing through his torso. He died instantly.

The following night, a reporter from the Philadelphia Inquirer witnessed Kearny’s autopsy, which traced the fatal bullet’s path through his body.

“Last night I visited the embalming establishment of Messrs. Brown and Alexander. It was midnight, and when your correspondent entered the retired precincts wherein many of the unfortunate victims of the Rebellion are prepared for removal to their former homes, the scene was impressive if not enticing. Stretched upon a board, awaiting the coming of the ambulances, was the body of him who but a few hours before was regarded and revered by the country as one of the bravest officers in the service–a man beloved by soldier and civilian. The pale but marked features, changed only in their appearance by their unnatural color, proved how speedily the fatal ball had sped its way. In everything but life we saw the gallant Kearney before us.

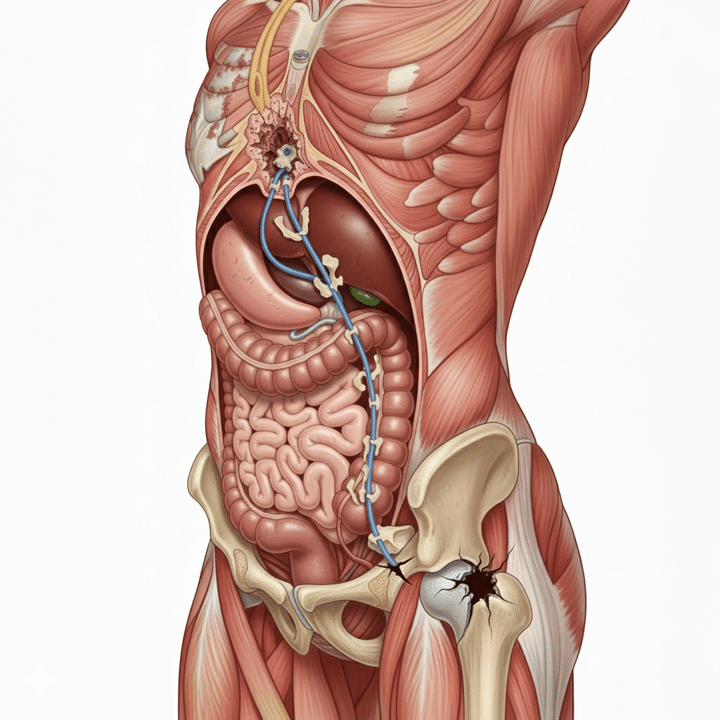

“Gen. Kearney was killed by a Minie ball entering the body through the gluteus muscles, at a point near the articulation of the hip joint. The missile striking the pelvic bones, turned upward through the abdomen to the integuments, under which it glided passing over the sternum and lodging just beneath the skin, just above the centre of the breast. The General must have been on horseback and leaning forward at the time of the reception of the ball.”

“Very Latest from Washington,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1862. (Written on September 3, 1862)

For more information on the Battle of Chantilly, read Dan Welch’s and Kevin Pawlak’s “Never Such a Campaign: The Battle of Second Manassas, August 28-30, 1862,” and Rob Orrison’s and Kevin Pawlak’s “To Hazard All: A Guide to the Maryland Campaign, 1862,” both published as part of the Emerging Civil War Series.

A tragic precursor of the death of Sherman’s Pet, McPherson during the Battle of Atlanta two years later. It never fails to astonish me how incredibly florid newspaper writers felt they had to be to capture the attention of their readers.

Fascinating drawing, Kevin, showing the path of the bullet. So much more visual than reading stark medical terminology. Did you deploy AI yourself to obtain this drawing?

I used Google Gemini to generate the image based on the description provided above. It took a few tries and some tweaking to get the type of image that I wanted.

Interesting post Kevin. Not too many understand how a bullet can ricochet inside the body, as opposed to a straight in and out. A modern example was the attempted assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan.

Glad you cleared up this mystery Kevin. A more incredible description of the entry wound evolved over the years, probably resulting from embellishments of the narrators.

Thanks for reminding us of the sobering reality of 19th century warfare and the terrible human damage caused by small pieces of metal … poor General Kearny never had a chance.

Another “To Substitute Reality for Fancy” image. (Ref ECW 8/30/25)