Confederate Leadership at Sharpsburg: Center Line, cont. Part 4

Sunken Road, Piper’s Farm, Hagerstown Pike

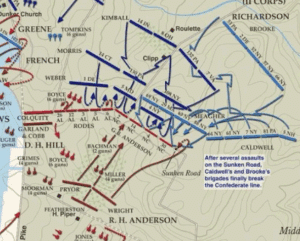

The time was around 10-10:30 a.m. D. H. Hill’s brigades had been fighting for almost an hour. His small force had repulsed several waves, but more Union brigades were arriving. The attrition rate was high in the Confederate ranks. Brigadier Geneneral G. B. Anderson was hit in the ankle and had to relinquish command. A bullet struck North Carolinian Col. Charles Tew in the head. He had been in the process of taking over Anderson’s brigade when he was killed. Reinforcements were needed. Unfortunately, the support that arrived only added to the casualty list and chaos.

Major General Richard H. Anderson’s division reached Sharpsburg exhausted. The seventeen-mile forced march from Harpers Ferry thinned the ranks. Men dropped out through the night, but those that made it reached the northern outskirts around sunrise. There was no time to rest. Lee sent one of Anderson’s largest brigades to bolster Jackson’s wing.[1] This left the division artillery battalion and four brigades. All toll, there were 16 short-range guns and 2,600 infantry.[2]

Lack of communication initiated the botched reinforcement effort. None of the senior officers provided R. H. Anderson with any direction. Instead, a staff officer, unaware or not thinking, led the division into a kill zone.[3] His 16 guns unlimbered on a ridge near Hagerstown Pike; Union 20-pounders opened up immediately. Their batteries outgunned the Confederate smoothbores. It was artillery hell. Shrapnel flew everywhere. Within minutes, the cannon, artillerymen, and horses were shot up. The gun crews got out of there, dragging their cannon tubes behind them.[4] Union artillery also played havoc on R. H. Anderson’s infantry. Scores went down killed or wounded. A shell hit Anderson in the thigh and took him out of the battle before his division even reached the Sunken Road.

As the senior officer, Brig. Gen. Rodger Pryor assumed command. His incompetence and inexperience further hampered the reinforcement effort. He didn’t coordinate with his new command nor with the Confederates already fighting in the lane.[5] The brigades ran through Piper’s Farm and piled into the crowded Sunken Road. Colonel Carnot Posey’s Mississippians recklessly stormed out of the defenses and straight into the blue coats. It was suicide. The Confederates charged into a “murderous fire.”[6] The Mississippians recoiled back into the defenses.

Another reinforcing brigade under Brig. Gen. Ambrose Ransom Wright at least extended D. H. Hill’s line to the right, but Wright went down with a bullet through the leg. Then, to the dismay of G. B. Anderson’s North Carolinians, Wright’s boys also charged out of the defenses and collided with the approaching enemy lines. The Union troops blasted the counterattack; survivors melted back into the Sunken Road.[7]

By now more Union brigades joined the fight, and the center defense broke at the Sunken Road. Several regiments got around the vulnerable Confederate right flank and sent a devastating enfilade fire down the line. The bullets that missed one soldier hit others farther away. At the same time, other blue-clad regiments making a frontal assault fired point blank into the defenders. A Yankee in the famous Irish Brigade later recalled:

“The shouts of our men, and their sudden dash toward the sunken road, so startled the enemy that their fire visibly slackened, their line wavered, and squads of two and three began leaving the road and running into the corn.”[8]

After an hour-and-a-half or so of fighting, the Rebs that remained made a run for it. A North Carolina officer described the retreat as a “stampede.”[9]

Though enough Confederate infantry regained their composure, it was all-hands on deck at the secondary defensive lines near Pipers Farm and Hagerstown Pike. Lee scrounged up other infantry units and sent them into the fight. Major General James Longstreet directed cannon fire, while his staff officers manned some of the guns. D. H. Hill directed other guns to blast Union troops swarming over the lane. Hill then picked up a musket and led 200 men or so on a counterattack. Other officers did the same. The blue clad regiments easily repulsed their foe.[10]

The lines now fought to a stalemate. Union brigades tried taking the second defensive, line but didn’t get far. Lee and Longstreet had positioned at least seventy-six guns behind Hagerstown Pike. Any attempt to charge up through Piper’s Farm was met with a hail of shot and shell. A Union officer remembered: “the enemy opened upon us a terrific fire from a fresh line of infantry and also poured upon us a fire of grape and canister from two batteries, one in the orchard just beyond the corn-field, the other farther over to the right….regiments bore this fire with steadiness.”[11] It was about 1:00 p.m. The slaughter subsided along the center of the line.

The Sunken Road earned the nickname “Bloody Lane.” Some Union soldiers described the carnage in the lane as “ghastly flooring.” Another Union soldier thought the bodies lay “as thick as autumn leaves along a narrow lane cut below the natural surface, into which they seemed to have tumbled.” A northern correspondent wrote: “The Confederates had gone down as grass falls before the scythe. They were lying in rows like the ties of a railroad, in heaps, like cord-wood mingled with the splintered and shattered fence rails. Words are inadequate to portray the scene.”[12]

Casualties were high. D. H. Hill had five horses shot from under him, but miraculously survived uninjured. Rodes was hit, but not seriously. His Alabama brigade had gone into the fight with 850 and lost 219 men killed, wounded, or missing. G.B. Anderson took a bullet through the ankle. The leg had to amputated, and he died October 16, 1862. His North Carolina brigade went into the battle with 1,174. Out of that number, 525 soldiers became casualties. Every regimental and field officer was either killed or wounded, save for one major in the 30th North Carolina. The 4th North Carolina had an orderly sergeant commanding the survivors; there were no officers. R. H. Anderson’s division suffered 1,271 casualties out of 3,712. Some fell in Piper’s Farm and others in the Bloody Lane. It was a terrible price to pay. Lee’s center was battered, but his secondary line remained formidable.[13] As the primary fighting subsided on the left and center, the battle continued on the right flank.

[1]Anderson counted six depleted brigades. One of the larger brigades was Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead’s brigade, commanded by Col. James G. Hodges. Armistead was on Provost Marshall duty during the Maryland Campaign. https://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?officer_id=5&from=results.

[2] There were four brigades. Pryor’s brigade was commanded by Col. John A. Hately. Brig. Gen. Ambrose Wright led his command briefly. Col. Carnot Posey led Featherston’s brigade. Posey’s command had the remnants of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade in it. Mahone was recovering from a wound. Col. William A. Parham led the brigade. It was a small command, and its regiments got shot up pretty bad at South Mountain, leaving it with only 82 soldiers. The fourth brigade was Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s. He was sick so Col. Alfred Cummings led the brigade.

[3] R. H. Anderson or Pryor should’ve asked someone who was familiar with the details of the battle in this sector. McLaws got details of the West Woods prior to his brigades going into the fight. Hartwig also feels Lee or Longstreet or D. H. Hill should’ve provided guidance to Pryor. My question is, did Pryor ask any of his superiors?

[4] Hartwig, 333-34. Major John Saunders commanded the artillery battalion.

[5] Historian Robert E. L. Krick describes Pryor as “incomparably incompetent.” For quote about Pryor and Anderson wounded, Ibid., 332 and 335.

[6] Report of Captain A. M. Feltus, 16th Mississippi Regiment, O.R., Ser. 1, Vol. 19, Part 1, 884-885. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924079609610&view=1up&seq=900.

[7] Hartwig, 339-40. Wright’s counterattack may have occurred before Posey’s brigades. There was also talk that Wright was drunk during the battle.

[8] Until Antietam: The Life and Letters of Major General Israel B. Richardson, U.S. Army by Jack Mason. Carbondale IL: Southern Illinois Press, 2009. See also: https://jarosebrock.wordpress.com/maryland-campaign/antietam/the-sunken-road/.

[9] Col. Risden Bennett of the 14th North Carolina used the word “stampede,” Hartwig, 362.

[10] For Longstreet and his staff officers fighting see Ibid., 381 and Hill, Ibid., 368.

[11] Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell, O.R., Ser. 1, Vol. 19, Part 1, 284-87.

[12] All quotes from “It Appeared As Though Mutual Extermination Would Put a Stop to the Awful Carnage Sharpsburg’s Bloody Lane,” by Robert K. Krick. The Antietam Campaign. Ed. Gary Gallagher Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

[13] Hartwig, 388 and Appendix Strength and Casualties-Army of Northern Virginia.

Old fire-eating Cousin Roger Pryor almost won the war for the Union that day! Bumbling idiot!