Lessons from Lincoln in our Current Political Moment

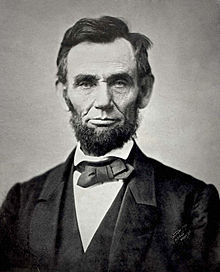

Like many people, I have been deeply troubled by the recent string of political violence in our country and equally troubled by the reaction of some Americans to these murders. As liberals and conservatives argue over which acts of violence are more significant, who or what is responsible, and which party is ultimately to blame, it can be difficult to have faith in the American experiment. In a time when democracy seems so fragile, I thought it prudent to seek advice from one of America’s greatest unifying voices: Abraham Lincoln.

Of course, Lincoln was no stranger to violence. Indeed, he was himself the victim of a political assassination, and he oversaw one of the bloodiest chapters of American history—the Civil War. Nor was Lincoln, by any means, a violent man. His view of democracy hinged on the prospect of peace.

Early in the war, Lincoln wrote to Cuthbert Bullit, a staunch Unionist and Louisiana U.S. Marshal who had passed on concerns about the president’s “forceful” treatment of the Confederate state. In his letter, Lincoln justified the emancipation of slaves as a war measure and affirmed his commitment, above all, to preserve the Union. Notably, though, the president closed his letter by stating, “I shall do nothing in malice. What I deal with is too vast for malicious dealing.”[1]

That statement guided Lincoln as he attempted to “bind up the nation’s wounds” in the last days of the war. Of course, it also directly foreshadows his famous line “with malice toward none” and “charity for all” in his Second Inaugural Address, delivered nearly four years after his letter to Bullit.[2] Though he did not plan to graciously extend pardons to Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis, Lincoln hoped to turn a blind eye as they escaped Federal custody and went into exile. That would preclude Davis’s capture and prosecution from becoming the object of ex-Confederate bitterness and an instrument of Radical Republican requital.[3]

To Lincoln, peace after the Civil War did not mean retributive trials and vengeful executions. He understood that democracy was not built upon the gallows or any sort of vindictiveness or retribution—and certainly not upon malice.

In an age when hateful sentiments seem to transcend the highest and lowest levels of our republic, it’s important to recall Lincoln’s maxim of “malice toward none,” no matter what political ideologies we might embrace.

Notes:

[1] Abraham Lincoln, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 5, Oct. 24, 1861-Dec. 12, 1862, (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 346.

[2] Abraham Lincoln, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 8, Sept. 12, 1864-Apr. 14, 1865, (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 333.

[3] Allen Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 423.

Although I agree with Lincoln’s sentiments in his second inaugural address and believe Reconstruction would have been much smoother had he survived, I’d hardly call Lincoln a “unifying figure.” He’s the only president whose election led to a Civil War.

Actually, the election of Lincoln caused the South to leave the Union.

it is the Confederate States that started the Civil War by firing on Fort Sumter.

There wouldn’t have been a war at all if the Southern states hadn’t attempted to secede

Pickett said of the Confederacy losing the war, “I think the Yankee army had something to do with it,” In that veign I’d say slavery was the cause of the war. I’d agree if one said the war was going to happen no matter what and it would start when a strong president got elected.

The South attacking Fort Sumter initiated the Civil War. Lincoln called for 75,000 troops AFTER the attack on Fort Sumter…not before.

Recall that the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision did not extend rights other than Afro-Americans and invalidated the Missouri Compromise the the Compromise of 1820, allowing property to be taken to all states and territories. So the South had a SC court decision validating slavery.

Plus Lincoln had stated he was not going to interfer with slavery in the states where it already existed.

The US Constitution was a pro-slavery document. The 3/5ths clause allowed Southern states to have more representation in the House. The Electoral College where the South had additional votes gave more power to the South. And the President nominates the justices to the Supreme Court.

Plus, recall the Preamble of the US Constitution….In order to make a more perfect Union. The term “more perfect” implies that the process of improving the union is ongoing and never truly complete, reflecting an aspiration for continuous progress and refinement of the American governmental experiment. The Articles of Confederation, the original document that was being built upon, states the Union is to be perpetual.

Nice try though.

I have removed a reader comment from this thread that endorsed political violence.

Thank you Chris. There is no place for that anywhere.

Well said!

Very nice sentiments Evan at just the right time … I would add, also from his 2nd inaugural address, Lincoln suggested that the dreadful toll of the war was God’s retribution for 250 years of slavery … and “until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword” … from Psalm 19 “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”