Dead Horses on Nicodemus Heights, According to the Elliott Antietam Burial Map

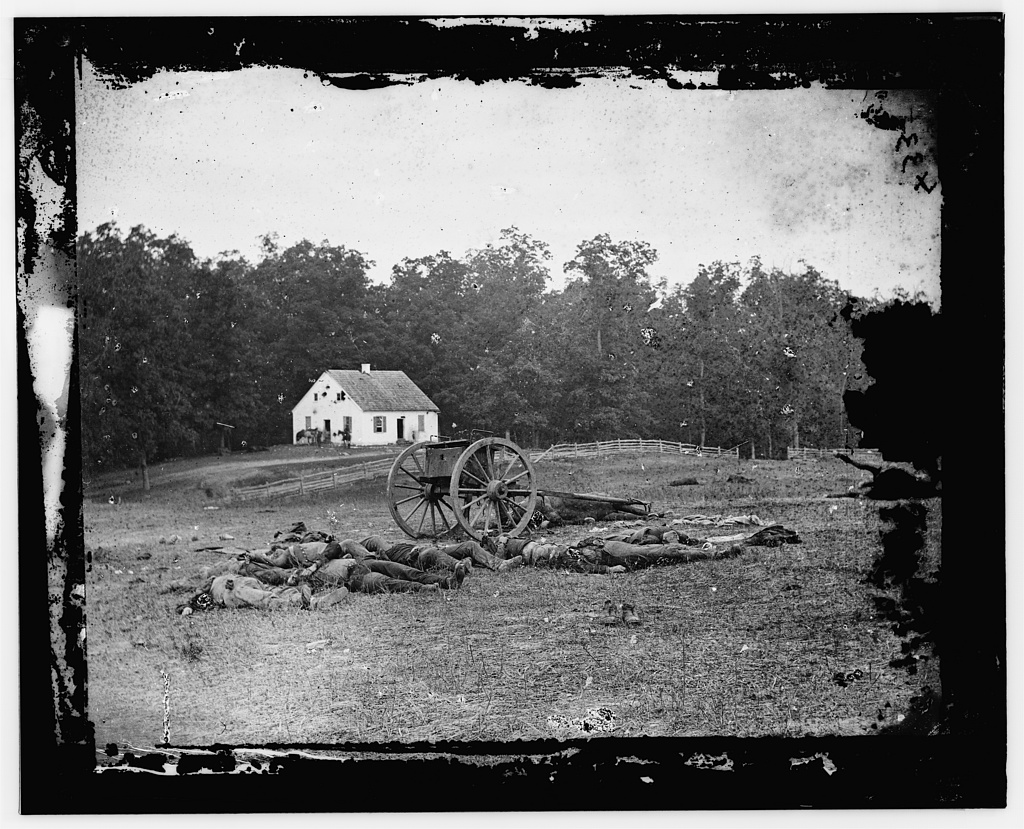

If you only glance quickly, it could be an image of a horse reclining restfully. Then, once you look closer or read the caption, you can’t unsee it. This is a dead horse.[i] A dead pale horse—like the horrors of tribulation prophecies—but in motionless reality in the aftermath of the battle of Antietam.

Dead horses also appear in other photographs from Antietam Battlefield. Like the one trapped beneath part of a caisson in front of Dunker Church.[ii] Or the one barely in the left foreground of Knapp’s Battery photograph taken shortly after the September battle.[iii]

This battle resulted in nearly 23,000 human casualties and is usually called “the single bloodiest day in American history.” Rightfully, most studies of battle aftermath and identification and burial of the dead focus on human loss. However, details about equestrian casualties can add missing details or hints while studying the battle, especially for artillery batteries.

Horses or mules pulled field artillery pieces into position during the American Civil War. Typically, six horses pulled a cannon, limber, and caisson. In field artillery, the cannoneers walked or hitched rough rides on the ammunition chests. In horse artillery, the gunners were mounted, riding alongside the pulled cannons with all able to move at horse-speed and thus keep up with the cavalry. For both field and horse artillery cannons, if the horses were killed or otherwise incapacitated, it became extremely difficult to move those heavy guns. In some battle reports, artillery officers noted horse losses in their post-battle casualty lists.[iv] Dead horses could spell extra danger for now immobile cannons. Wounded horses could stampede, rushing ammunition or guns away from the cannoneers. While minorly injured horses would usually be calmed and eventually nursed back to health, artillerymen had to put mortally wounded animals out of their misery. In the aftermath scenes of Civil War battlefields, horse corpses were often dragged into piles and burned; it was too difficulty to dig holes large enough to properly bury them.

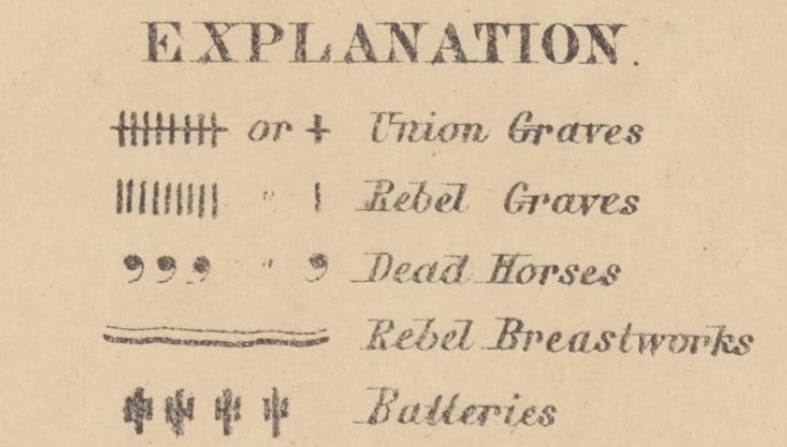

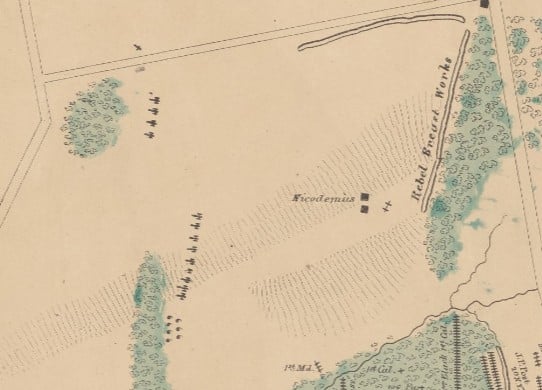

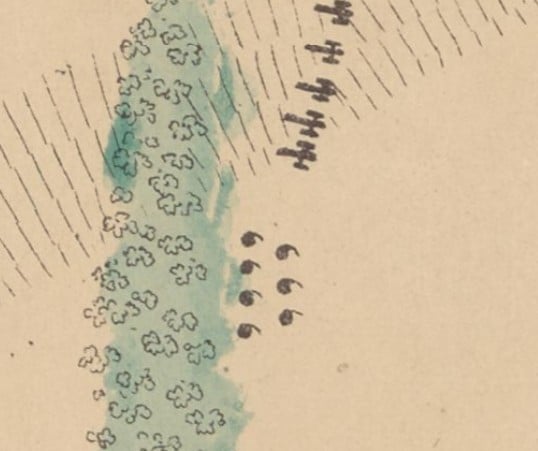

The Elliott Antietam Burial Map came to light in 2020, adding knowledge and questions to the research of Antietam Battlefield after the bloody conflict on September 17, 1862.[v] S.G. Elliott created the map in 1864, marking more than 5,800 graves of Union and Confederate soldiers. Studying the map has produced corroboration of the visual details of the burial of the dead in Alexander Gardner’s photographs and better understandings of the battlefield burials prior to the creation of Antietam National Cemetery. In addition to the thousands of human burials noted on the map, there are map icons for the locations of dead (and usually burned) horses. 269 equestrians in 40 locations, to be exact.[vi]

Earlier this year, I was looking at the grisly map and noticed a marked pile of horses on the high ground behind the Nicodemus House. This would be Nicodemus Heights, one of the artillery positions used by Major John Pelham. (Pelham hailed from Alabama, had nearly graduated from West Point, then entered Confederate ranks and in 1862 had been tearing up battlefields while commanding the Stuart Horse Artillery.) During the battle, Pelham commanded the guns of the Stuart Horse Artillery and also oversaw the placement and firing of the Staunton, Alleghany, Danville, and D’Aquin’s Louisiana Guard batteries which were sent to the position—a total of between 14 and 17 cannons.[vii] Later in the day, cannons from Brockenbrough’s, Raine’s, and Poague’s artilleries joined Pelham for an ordered attempt to test the Union’s left flank for the possibility of greater attack.

Unfortunately, there is not a known battle report for the Stuart Horse Artillery at Antietam, so there is not a reliable casualty report concerning men or horses. Looking at the Elliott Map, there are symbols for seven dead horses near the Confederate guns on Nicodemus Heights. Could these be dead horses from the Stuart Horse Artillery and from other batteries under Pelham’s command at Antietam? Probably. Could there have been more? Possibly. Elliott created his map in 1864, and it is simply not known at this time how he determined how many remains of horses he found at each location.

While Poague reported the loss of 14 horses (killed and wounded), other exact equestrian casualties from Confederate artillery on or near Nicodemus Heights has been difficult to track down. Pelham did have the cannoneers use the “reverse slope” of the high ground to give some protection for the men and horses. This meant that the recoil of the guns would have slid them behind the top or military crest of the hill; meanwhile, the horses with the limbers and caisson would likely have been positioned further down on the rear, protected slope to reduce their losses.

There is a mention of horses in Captain Samuel D. Buck’s reminiscences as he and other soldiers from the 13th Virginia Infantry rushed to assist as Pelham relocated some cannons.

“We charged, skirmished and then went to work assisting the horses to pull the artillery into position…. Major Pelham was trying to get two Napoleon guns on a hill commanding their position but the horses could not pull the over the plowed fields and up the hill so every fellow regardless of the shot and shell, too hold and almost carried both pieces into position and there…the Gallant Pelham fought those pieces, aiming and firing each piece as fast as the men could lead, while our men supported him and poured the lead into their flank.”[viii] (emphasis added)

The precise details of equine casualties along Pelham’s positions at Nicodemus Heights and Hauser Ridge at Antietam Battlefield are still elusive. However, the Elliott Map suggests that the remains of at least seven horses were discovered near the position of a Confederate artillery line on Nicodemus Heights. It is a reminder of the realties of battle death for man and animal and the added threats for artillery units that horse casualties could create.

John Pelham had been fond of horsemanship in his pre-war West Point years and, according to family stories, also helped his younger siblings learn to ride. After his first battle experience at Manassas in July 1861, Pelham wrote about seeing dead horses.

“I have heard the booming of cannon, and the more deadly rattle of musketry at a distance—I have heard it all near by and have been under its destructive showers. I have seen men and horses fall thick and flat around me…. I have passed over the battle field and seen the mangled forms of men and horses in frightful abundance.”[ix] (emphasis added)

Fourteen months later, Pelham fought on the high ground of Nicodemus Heights. He needed to keep the teams of horses nearby but sheltered whenever possible to keep the ability to move the cannons as needed. It is possible other horses in the artillery units under his command did not survive Antietam. However, the hint in the Elliott Map (seven dead horses) and the movement of artillery along Nicodemus Heights and Hauser Ridge suggest that Pelham successfully protected the artillery horses on the reverse slope. He kept an artillery battlefield advantage of moving cannons under threat or opportunity. He had kept many of the artillery horses from encountering Pale Death that day.

Read more in one of the newest books in the Emerging Civil War Series—Glorious Courage: John Pelham in the Civil War by Sarah Kay Bierle (May 2025).

Sources:

[i] Library of Congress, Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012650218/

[ii] Library of Congress, Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018667420/

[iii] Library of Congress, Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2025163968/

[iv] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Volume 19, Part 1. William T. Poague’s Report. Pages 1109-1010.

[v] Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Map of the battlefield of Antietam” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8f4c0d60-4fb1-0135-a8e7-08dfeed19acf

[vi] National Park Service, Elliott Antietam Burial Map : https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/elliott-antietam-burial-map.htm

[vii] James A. Rosebrock, Artillery of Antietam: The Union and Confederate Batteries at the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg: Antietam Institute, 2023), page 332.

[viii] Robert H. Moore III, The 1st and 2nd Stuart Horse Artillery (Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, 1985), page 34

[ix] John Pelham, Letter, Jacksonville Republican, August 8, 1861 – Jacksonville Pubic Library, Pelham Collection.

See also: Robert J. Trout, Galloping Thunder: The Stuart Horse Artillery Battalion (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2002).

Very interesting article. It’s unfortunate horse and mule casualties weren’t tracked more precisely. It’s just something in the background that historians don’t usually think about.

Great inductive reasoning! Really enjoyed reading this.

Thanks Sarah … a thoughtful piece on a little studied field … i had never seen your first photograph — you’re right about not being able to unsee it — very sad … i think i read somewhere that between one and two million horses and mules died in the war.

That horse photo is haunting. As a former horse owner, I know how individual each horse’s personality can be. It’s hard to see them as “just” animals.

Great article. That unfortunate horse is a hard to look at. They are such beautiful animals. I worked as a trail guide for many years when I was younger and can attest to the fact that they have unique, wonderful, and intelligent personalities. They could read the riders feelings immediately upon saddling up. They knew who was nervous and who they could take advantage of. I loved the fact that when we experienced riders got together they wanted to let loose as soon as we started. They knew it was go time and the Quarter Horse (named Pride) I always rode could hardly wait. He loved to run. Smoothest horse I ever rode. We always had to seriously hold them back until we got to where we would give them the reigns and let them go. Thanks for the article and bringing back great intellegent.

Oops! Meant bringing back great memories.