Netflix’s Death by Lightning and the Army Medical Museum

Netflix has just launched their new limited series Death by Lightning. The show follows James A. Garfield’s ascent to the presidency and assassination while also trying to unpack the complicated story of assassin Charles Guiteau. Michael Shannon stars as James A. Garfield, while Matthew Macfayden portrays Charles J. Guiteau. Betty Gilpin stands out as Lucretia Garfield, who was instrumental in shaping the memory of her late husband, and Nick Offerman appears as Chester A. Arthur.

I only just finished the four-episode series. While it stretches the history at times, there have also been many moments I was impressed with it. I’ve been excited for it for some time, and when I saw the very first scene of the show I knew I had to talk about it and its ties to the Civil War.

While primarily set after the Civil War, the ghosts of the war are constantly apparent. There are brief but powerful flashbacks, wounded veterans, and consistent mention. Garfield rose to the rank of major general during the war, earning distinction at Chickamauga before resigning from the military to serve in Congress. The politics of the war and Reconstruction are all around, and many names will be very familiar to readers. There is much to unpack about the show and the forgotten legacy of Garfield, and though I hope others do that this article instead focuses on the brief opening scene.

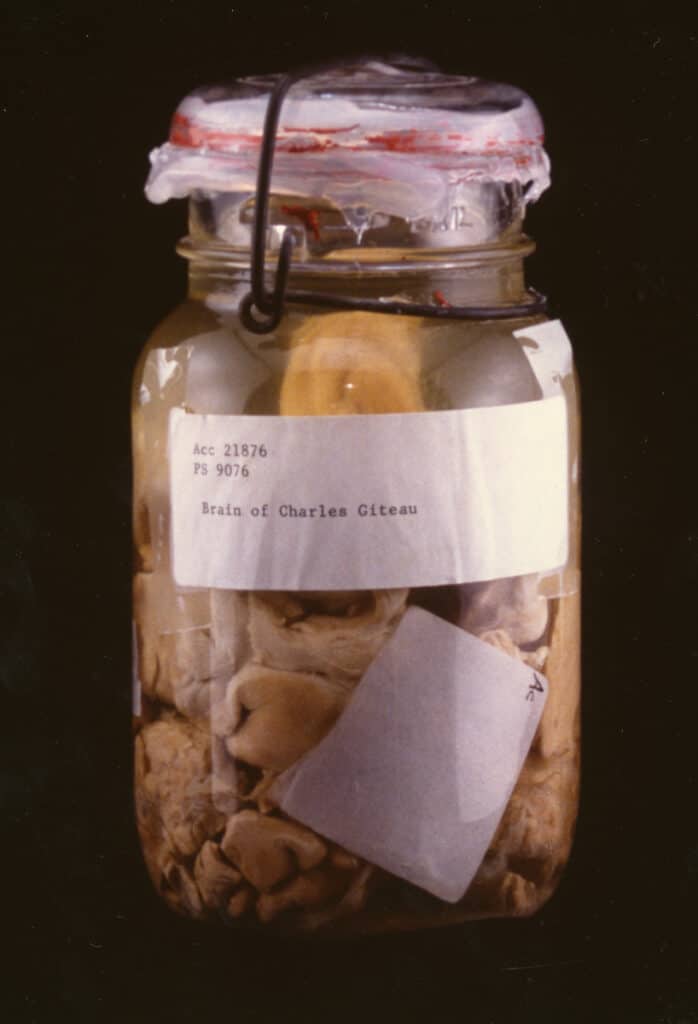

The show begins in a warehouse in 1969. Revealed to be the Army Medical Museum, workers are moving around boxes. A jar falls to the floor and rolls briefly. A man picks it up, revealing that it holds a preserved brain. He reads the label, and reacts, “Who the f*** is Charles Guiteau?”

That’s one question the show seeks to answer (though it also stretches some aspects, adding him into discussions and events he likely wasn’t at). After all, in the list of presidential assassins Guiteau’s name is far less known than John Wilkes Booth. Guiteau shot President Garfield on July 2, 1881, though Garfield lingered for a painful 79 days where medical intervention likely made things worse. After Guiteau’s execution, his brain was preserved and studied by the Army Medical Museum. Doctors had hoped that studying the brain might reveal answers for what drove Guiteau to shoot Garfield.

The Army Medical Museum was born of the Civil War. As the United States army struggled to apply modern medicine to the treatment of soldiers, they knew the necessity of gathering information and disseminating it to surgeons. In 1862 Surgeon General William Hammond issued Circular No. 2 directing medical officers “to collect…all specimens of morbid anatomy, surgical and medical, which may be regarded as valuable; together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed, and such other matters as may prove of interest in the study of military medicine or surgery” and send them to Washington, D.C. for the creation of the Army Medical Museum. [1]

These specimens, including limbs amputated from wounded soldiers, or organs removed from those who died of illness, were studied to understand successful or failed treatments while also displayed to visiting members of the public. Though the ethics of collection and display are debatable, it was a popular attraction at the time, with the collection growing to over 4,700 specimens before it was moved to Ford’s Theatre following the war. These specimens and the reports written by surgeons during the war formed the basis for the immense volumes of the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion.

The Army Medical Museum has evolved over time, and is now the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. The museum maintains sizeable collections, still including the original Civil War collections. In addition to Guiteau’s brain, which was part of a 2013 exhibit on brains, it holds a great deal of paperwork on the assassination (such as the original autopsy) as well as specimens related to Lincoln’s killing. The museum’s core mission remains the same as it was in 1862: gather specimens for the dual purposes of training medical professionals in successful treatment methods and curating exhibits for the public.

Courtesy National Museum of Health and Medicine. https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2013/09/20/the-president-is-somewhat-restless-aftermath/

So far, critics agree that the show is worth a watch. I’m hoping to sit down with some popcorn and see the rest soon! For folks looking to learn more about Garfield, there’s no shortage of information. There’s a number of ECW articles to explore here and here. Dan Vermilya’s book James Garfield & the Civil War covers the wartime life of the man, which is not covered in depth in the series. Candice Millard’s 2011 book Destiny of the Republic is the basis for the show; it’s an excellent book that follows both men and the politics of the age. James Garfield National Historical Site in Mentor, Ohio is also a must-see site (which appears in the show) with knowledgeable staff, powerful exhibits, and a chance to see how his family wanted him to be remembered. I am optimistic that the show will help raise the profile of a significant man sometimes missed in retrospective.

[1] For more on Circular No. 2 and the Army Medical Museum, you can see my previous journal article here. Tracey, Jonathan (2019) “The Utility of the Wounded: Circular No. 2, Camp Letterman, and Acceptance of Medical Dissection,” The Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era: Vol. 9, Article 3.

I watched it and found it very entertaining. The history is a bit muddled but that’s Hollywood. However you do get a good sense of the times, especially the corruption that existed.

Thanks Joe! I agree there’s some stretch there, but introducing broad audiences to this is something to celebrate.

Great piece, Jon. I’m enjoying watching it as well, and it was cool to learn more about the first scene!

Thank you, Evan. There’s so much to unpack here, there could be multiple posts like this for every episode.

I have enjoyed a couple episodes and look forward to watching the rest. Admittedly, I don’t know much about James Garfield. Time to buy a book. One trivia that I was aware of, Garfield’s assassination compelled Congress to pass the Pendleton Act of 1883, which established a merit-based system for hiring civil servants.

Yes – Garfield really believed in a merit-based civil service system, free from political patronage. A noble goal.