Wiedrich’s Battery at Gettysburg

Gettysburg is full of gallant artillerists. But no battery made a more ferocious stand during the battle than the German Americans of Capt. Michael Wiedrich’s Battery I, First New York Light Artillery.

An Alsatian-born German who immigrated to the United States before the war, Wiedrich was a shipping clerk for Pratt & Letchworth when he decided to enlist in the 65th Regiment of the New York State Militia. In 1861, he received permission from the War Department to raise his own artillery battery in response to the rebellion.

Organized into about 140 men (mostly German immigrants) from Buffalo, Battery I, First New York Light Artillery prepared to leave for the Union army on October 25, 1861. “It is composed of a splendid set of men, stout, intelligent, soldierly-looking German citizens,” the Buffalo Morning Express said of Wiedrich’s battery, “and has attained a proficiency in drill and experience in the handling of its artillery that fit it for immediate service in the field.”[1]

The Rochester Democrat echoed with similar sentiments: “They are a splendid-looking lot of men, all hale and hearty, most of them above medium size. Many have seen active service in Europe, and will be found to be good soldiers in America.”[2] As Wiedrich’s men marched through Buffalo on their way to the war, they sang three songs in their native tongue to bid their city farewell.

The battery soon saw its first engagement at the battle of Cross Keyes on June 8, 1862, while serving in Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont’s army. Two months later, it helped delay Longstreet’s counterattack at the battle of Second Manassas. Deployed on the Union army’s left flank and guarded only by four Ohio regiments, Battery I faced overwhelming odds as Gen. James Kemper’s Confederate division came crashing down on its left. Here, Wiedrich’s battery paid a high price of 14 men wounded as well as one piece captured by Confederates on the field.[3] During the battle, a single shot from a Confederate cannon took the arm of Sgt. William I. Moeller and the leg of Lt. Jacob Schenkelberger.[4]

After returning to Washington, D.C. to be resupplied and refitted, Wiedrich’s men were attached to the Union Army of the Potomac’s XI Corps, comprised of many other fellow German immigrants. On May 2, 1863, the battery was again forced to confront overwhelming odds, this time during Stonewall Jackson’s flank attack at Chancellorsville.

Deployed south of the Plank Road, Wiedrich ordered his men to their hold fire as soldiers of the XI Corps began streaming past them in retreat. “As soon as the infantry were out of our way [we] opened with canister with good effect and checked the advance of the enemy for a short time,” Capt. Wiedrich wrote.[5] As Jackson’s men began to swarm the guns, Wiedrich gave the order to retreat. However, his men were again forced to abandon two pieces on the field. The day again proved costly for Battery I: 10 men were wounded, two were captured, and one was killed.

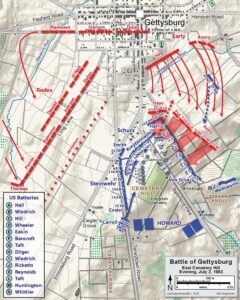

Though the gunners performed gallantly at Second Manassas and Chancellorsville, Wiedrich’s men were looking for redemption in the summer of 1863—along with the rest of the XI Corps. When the battery arrived in Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 1, 1863, Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard directed them to unlimber on East Cemetery Hill and fire on Confederate guns on Oak Hill. However, Howard noted that most of the battery’s shells fell short.[6] By late afternoon, the I and XI Corps positions gave way to a retreat through town. Wiedrich and his Germans held firm and fired canister into the Confederate pursuers as Union troops fled through Gettysburg and rallied on Cemetery Hill.

The gunners spent that night and the following day digging lunettes and firing test shots. By the evening, the fields surrounding Cemetery Hill were marked. Wiedrich’s men knew exactly when and where to use solid shot, case shot, or canister as well as how long to leave each fuse. Their preparation was tested as Confederate guns opened on Cemetery Hill in concert with Gen. James Longstreet’s attack on the Union left. Wiedrich’s battery, alongside other I and XI Corps batteries, participated in the artillery duel with Maj. Joseph Latimer’s battalion of guns across the valley on Benner’s Hill. “The very ground beneath us began to seemed to shake,” wrote a spectator from the 153rd Pennsylvania.[7]

However, the xenophobic Col. Charles Wainwright, commander of the Union artillery on East Cemetery Hill, was unimpressed with Battery I’s performance, despite their preparation during the day. He accused the Germans of incorrectly setting their fuses and called Wiedrich an “old man” who knew “little more” about artillery than his men. Wainwright instead hovered over the Germans and set their fuses for them.[8] Despite this, Wiedrich’s men stood firm during the bombardment.

As dusk settled upon the battlefield, two brigades of Confederate infantry (under Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays and Col. Isaac Avery) stepped off in an attack on East Cemetery Hill. The assault was swift and devastating. The XI Corps infantry, huddled in a farm lane at the foot of the hill, poured a devastating fire into the attackers, but the Rebel onslaught proved too powerful.

Two Ohio regiments—the 25th and 107th Ohio—began to break on the northern slope while Col. Leopold von Gilsa’s brigade fell back from the farm lane. The Ohioans quickly withdrew to the safety of Wiedrich’s guns with Louisiana Tigers a few paces behind them.[9] The gunners of Battery I protected their pieces with anything they could find. Rammers and handspikes became melee weapons. “The arms of ordinary warfare were no longer used,” remembered a soldier of the 153rd Pennsylvania. “Clubs, knives, stones, fists,—anything calculated to inflict pain or death was now resorted to.”[10] Wiedrich himself recalled desperate hand-to-hand fight as Confederates “got into the intrencments [sic] of my battery.”[11]

In one dramatic scene, a Rebel color bearer planted his flag on one of Wiedrich’s cannons, only to be shot down. Then an Irishman of Hays’s Louisiana brigade picked up the flag, but he, too, was shot. Finally, a Confederate captain rescued the flag just as he was shot in the arm. After mounting the cannon and cheering three times, a ball struck his chest, and he fell to the ground.[12]

Another brave Louisiana Tiger stood in front of one of Wiedrich’s cannons and claimed, “I take command of this gun!” The sturdy German gunner looked the Rebel in the face and replied, “Du sollst sie haben!” (“Then you shall have it!”) and yanked the lanyard.[13] By then, reinforcements from Gen. Carl Schurz’s division and Col. Samuel Carroll’s II Corps brigade had arrived to push the Confederates back. As one XI Corps soldier put it, “The day [was] ours; Chancellorsville redeemed.”[14] Wiedrich’s gunners manned their pieces during the cannonade of July 3, but they had succeeded in protecting their guns and holding Cemetery Hill.

Later that year, the battery transferred to the Western Theater along with the rest of the XI Corps. They saw action at Lookout Mountain, Kennesaw Mountain, Peach Tree Creek, and the Siege of Atlanta. Of all their engagements, though, the men of Battery I looked upon Gettysburg and the defense of Cemetery Hill as their crowning achievement during the war.

In May 1889, thirty-two survivors of the battery gathered on East Cemetery Hill for the dedication of their monument. Michael Wiedrich gathered them into line, while the regimental historian, Cyrus K. Remington, delivered an address. “These columns will turn to dust, time will with its finger erase all impress from this crumbling stone,” he remarked, “but the fame of those heroes remains evermore.”[15]

Notes:

[1] Cyrus Kingsbury Remington, A Record of Battery I, First New York Light Artillery, otherwise known as Wiedrich’s Battery, during the War of the Rebellion, 1861-’65, (Buffalo, NY: Press of the Courier Company, 1911) 11.

[2] Remington, A Record of Battery I, First New York Light Artillery, 12.

[3] John J. Hennessey, Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 387.

[4] Remington, A Record of Battery I, First New York Light Artillery, 13.

[5] OR, ser. I, vol. 25, pt. 1, 647.

[6] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 703.

[7] W.R. Kiefer, History of the One Hundred and Fifty-third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers Infantry (Easton, PA: The Chemical Publishing Co., 1909), 86.

[8] Charles Wainwright, A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861-1865, ed. Allan Nevins (New York: Harcourt Brace & World, Inc., 1962), 244.

[9] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 358.

[10] Kiefer, History of the One Hundred and Fifty-third Regiment, 87.

[11] OR, ser. I, vol. 27, pt. 1, 752

[12] Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 269.

[13] Kiefer, History of the One Hundred and Fifty-third Regiment, 87.

[14] Kiefer, History of the One Hundred and Fifty-third Regiment, 87.

[15] Remington, A Record of Battery I, First New York Light Artillery, 81.

Thanks for sharing the story of this unit. I had read of their incredibly heroic defense on East Cemetery Hill. Many of the II Corps reinforcements praised their efforts.

Thanks, Mike!

Interesting piece about this unit, and good to see them getting due praise.

I note the observation by the Rochester Democrat that many men of the battery had seen action in Europe. Evan any idea if that claim is accurate? Did it mean that they had served in the artillery or just that they had seen some type of combat, perhaps in revolutionary fighting in Europe?

Great question. I don’t have any idea as to the veracity of that statement, but I would imagine it could be true, given the military experience of many of the Forty-Eighters. If it’s true, it might make for a good blog post!

Good summation of the strength and courage of the men of Battery I at Gettysburg. Thank you for the report.

Keith Young

Thank you!

Great job … thank you for your well-crafted account of this little known action late on 2 July … in his official report, Colonel Wainright had high praise for Wiedrick’s and Rickett’s batteries as he believed these gunners turned back the Confederate attack by themselves.

The colonel wrote, “… their (the Lousiana troops) right worked its way up under cover of the houses, and pushed completely through Wiedrich’s battery into Ricketts’. The cannoneers of both these batteries stood well to their guns, driving the enemy off with fence-rails and stones and capturing a few prisoners. I believe it may be claimed that this attack was almost entirely repelled by the artillery.”

That’s probably the nicest thing Wainwright said about the Germans of the XI Corps!

Great article! The fact that the Wiedrich’s unit lost three artillery pieces and suffered so many casualties at Cross Keyes and Chancellorsville speak to their courage and determination to hold their ground in the face of the enemy as they did so well at East Cemetery Hill as well. Another example of the underrated fighting ability of the XI Corps at Gettysburg.

The XI Corps is definitely underrated!

Stuart Demsey would concur