Framing History: Funding Freedom

ECW welcomes back guest author Melissa A. Winn.

One of the subjects I’ve focused my historic image collecting on is a series of photos of formerly enslaved children from New Orleans. I’m especially intrigued by their use for fundraising, a novel concept in photography’s early years, and the use of props, posing, and other techniques to shape the message and story the images tell.

In December 1863, Col. George Hanks of the 18th Infantry, Corps d’Afrique, accompanied eight emancipated slaves from New Orleans to New York and Philadelphia to visit photographic studios as part of a publicity campaign promoted by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks of the Department of the Gulf and by the American Missionary Association and the National Freedman’s Relief Association. The campaign’s purpose was to raise money to educate former slaves in Louisiana, a state still partially held by the Confederacy. One group portrait, several cartes de visite of pairs of the students, and numerous portraits of each student were made. The group photo was also published as a woodcut in Harper’s Weekly in January 1864 and was accompanied by the biographies of the eight emancipated slaves, which served successfully to fan the abolitionist cause.[1]

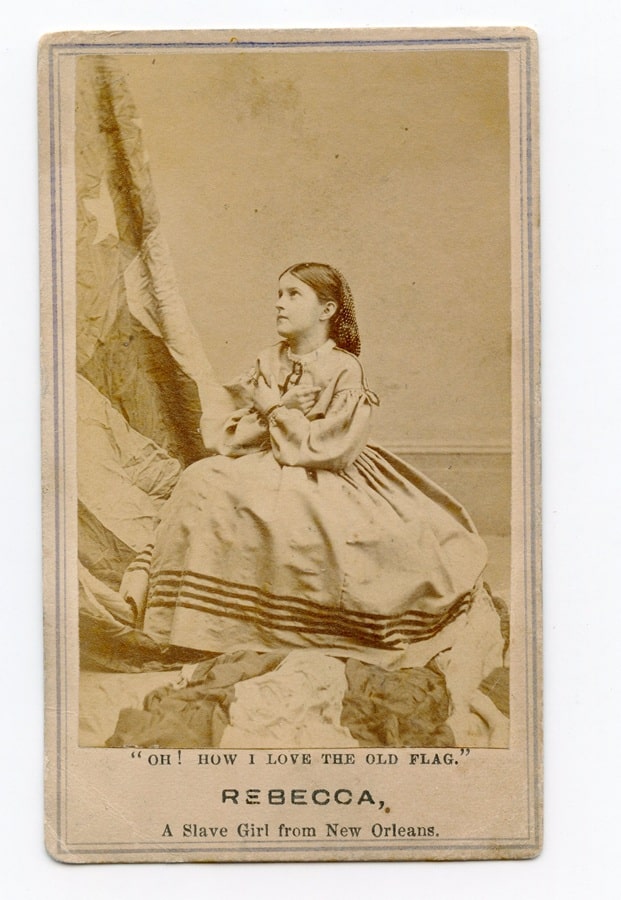

Several images were made of Rebecca Huger, 11, Charles Taylor, 8, and Rosina (Rosa) Downs, 7, presumably because their mostly Caucasian appearance made them more relatable to the intended audience. The images also drew attention to the fact that slavery impacted children, as well. If a child’s mother was enslaved, he or she was enslaved, too. [2]

The emancipated slaves were also photographed with props to imply that the subjects shared the viewers’ values. Several portraits use the American flag, including one of my favorite images, with Rebecca, captioned “OH! HOW I LOVE THE OLD FLAG.” Rebecca Huger is eleven years old here, and, according to the Harper’s Weekly article, “was a slave in her father’s house, the special attendant of a girl a little older than herself. To all appearance she is perfectly white. Her complexion, hair, and features show not the slightest trace of negro blood. In the few months during which she has been at school she has learned to read well, and writes as neatly as most children of her age. Her mother and grandmother live in New Orleans, where they support themselves comfortably by their own labor.”[3]

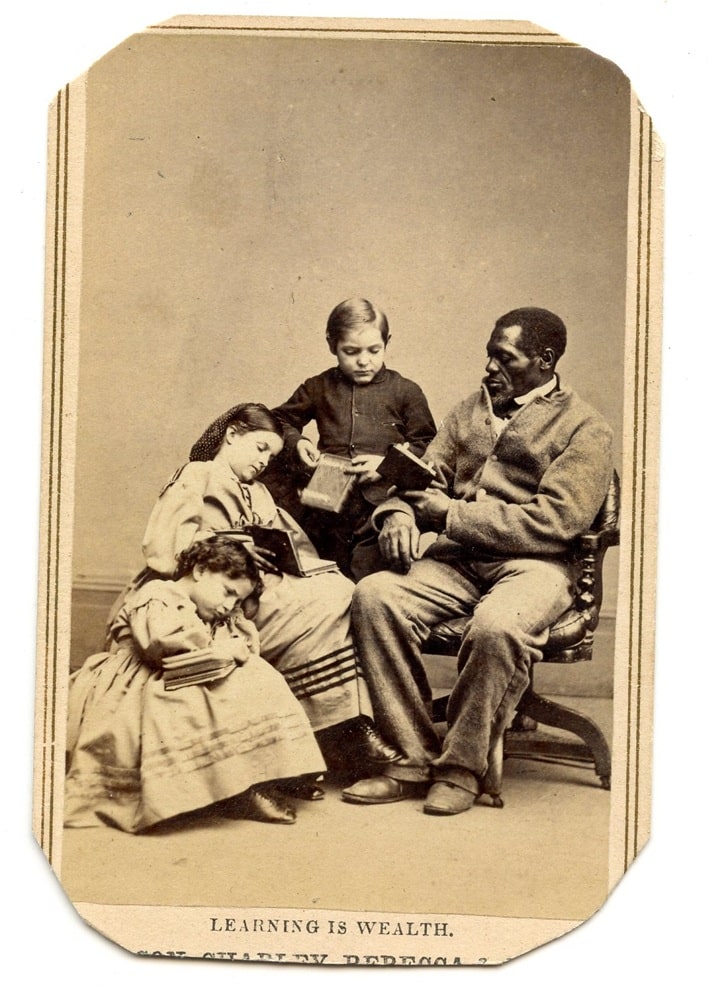

An image called “LEARNING IS WEALTH” includes the three children and Wilson Chinn. In the photograph, Rosa appears unable to hide her frustration, which suggests that Wilson is given the role of the teacher in the photograph. The image clearly intends to suggest the formerly enslaved can integrate into society if they can be educated. The Harper’s Weekly article published Wilson’s biography as follows:

“Wilson Chinn is about 60 years old; he was “raised” by Isaac Howard of Woodford County, Kentucky. When 21 years old he was taken down the river and sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. This man was accustomed to brand his negroes, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters “V. B. M.” Of the 210 slaves on this plantation 105 left at one time and came into the Union camp. Thirty of them had been branded like cattle with a hot iron, four of them on the forehead, and the others on the breast or arm.”[4]

The group photo of the slaves and lithograph based on it in Harper’s Weekly highlight the brand on Wilson’s forehead to dramatic effect.

Of the many prints that were commissioned, at least twenty-two remain in existence today. Most of these were made by photographers Charles Paxson and Myron Kimball, who took the group photo that later appeared as a woodcut in Harper’s Weekly. These images provided a key human face to the enslaved, while simultaneously acting as a critical fundraising source for continued emancipationist activity.

Melissa A. Winn is the Director of Marketing and Communications for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Previously, she was the Marketing Manager for the American Battlefield Trust and Director of Photography for HistoryNet, publisher of nine history-related magazines, including America’s Civil War, American History, and Civil War Times. She’s a Senior Editor for Military Images magazine; Editor of Shavings, the member newsletter of the Early American Industries Association, is a member of the Board of Directors of the Civil War Roundtable Congress; and President of the Bull Run Civil War Round Table.

Endnotes:

[1] “Slave Children,” Harper’s Weekly, January 30, 1864.

[2] Several other images of the same children and freed people are housed in the Library of Congress.

[3] “Slave Children,” Harper’s Weekly, January 30, 1864.

[4] Ibid.

There is another photograph of Chinn wearing the iconic spiked iron collar and chains. Massachusetts troops took another such collar off an adolescent girl they discovered confined to a shed in New Orleans. The collar was send north as part of the anti-slavery effort, and is now in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. I saw it during a teachers’ workshop and got to handle it. Its heavier, colder and rougher than in the pictures.

I use the photographs in class, showing the kids and asking to identify which of the people are enslaved. Of course they all were, and the “white” appearing children were used not just because they were relatable to a white audience, but because it highlights without explictly describing, the sexual exploitation of enslaved women.

Branding on the face. Hot iron branding. Tell me that enslaved people were better off being slaves.