The Virginia Colonels: Divided Loyalties at the Outbreak of the Civil War

ECW welcomes back guest author Collin Hayward.

Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause by Ty Seidule sent shockwaves across Civil War scholarship for its bold criticisms of Robert E. Lee and its thesis that Lee had committed treason by siding with the Confederacy. Among Seidule’s supporting arguments is a claim that of the eight colonels from Virginia actively serving in the Army at the outbreak of the Civil War, Lee was the only one to choose loyalty to his state over loyalty to his oath as a commissioned officer.[1] Since the book’s publication, this claim has been commonly circulated, but it raises interesting questions. Who were these other colonels who were presumably his peers in the pre-war army? And was Lee’s decision to side with Virginia really an anomaly compared to his peers?

At the time of Virginia’s secession, there were seven colonels actively serving in the U.S. Army from Virginia. These men were John Abert, Edmund Alexander, Philip Cooke, Thomas Fauntleroy, John Garland, Thomas Lawton, and Lee himself.[2] Seidule may count René De Russy, who was born in Haiti, but appointed to West Point by Virginia, but he was not promoted to colonel until 1863, or Matthew Payne who was brevetted to colonel at the time of Virginia’s secession.[3] Other candidates could be either Washington Seawell or George Thomas, both of whom were promoted to colonel when the resignation of other officers created vacancies.[4] Of these men, Seidule is correct that only Lee served in the Confederate Army, but that does not mean that the other colonels all served the Union cause.

Of the men holding the permanent rank of colonel, Lee was the second youngest at 54 years old (after Cooke who was 52). Due to slow career progression and the absence of any mandatory retirement, many of these officers were elderly and infirm. Before the end of 1861, Abert and Payne had retired, and Garland and Lawson had died of natural causes.[5]

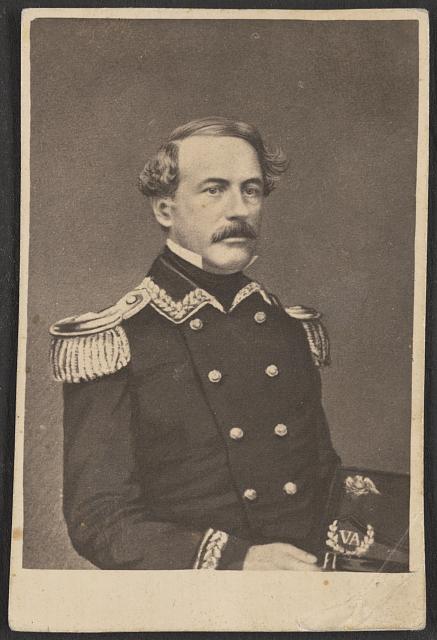

Of the men who were young and healthy enough to lead troops in the war, Lee was not the only one who believed he owed a duty to his state. Fauntleroy also chose to resign his commission and accept an appointment in the Provisional Army of Virginia, though unlike Lee, he chose to resign when the Confederacy absorbed Virginia’s forces. He had accepted an offer to command the defenses of Richmond and began the organization of the city’s defenses while in the service of Virginia, but when it became clear to him that he would be commanding militia instead of regulars and that he would be subordinated to men he had outranked in the pre-war Army, he ultimately declined a Confederate commission.[6] Fauntleroy’s decision to resign his federal commission, accept a commission from a newly seceded Virginia, and ultimately pursue Confederate command (despite later refusing it) demonstrates Lee’s decision was not anomalous.

Colonels Alexander and Cooke did continue their service in the Union Army, as did newly promoted Colonels Seawell and Thomas. Edmund Alexander was serving on the frontier at the outbreak of the war and continued that service until 1862, when he was appointed to serve in non-combat roles in Missouri until the end of the war. Philip St. George Cooke was the only one of these pre-war colonels who actively led troops against Confederate forces. He commanded the Cavalry Reserve of the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign. He left active service after ordering a disastrous charge at Gaines Mill and being humiliated by his Confederate son-in-law, General J.E.B. Stuart, on the same campaign. He supported recruiting efforts throughout the war and continued his service after the war.[7]

For those men capable of active service, the option to resign and take no part in the war was no option at all. While officers too elderly or infirm to perform duties commanding troops or attending to the vast administrative demands of the growing wartime armies were not expected to take an active role in the war, younger officers faced enormous social pressure to continue their Army service or to join the forces of their home state. Understanding why officers like Lee and Fauntleroy chose to resign their commissions to defend Virginia, while officers like Cooke and Alexander chose to continue their federal service requires analysis. Although Seawell and Thomas are interesting and compelling figures as Virginians who served the Union, they are excluded from this analysis because they were promoted to colonel because they had already made the choice to serve the Union. For the men already holding the rank, Virginia’s secession was a test of their loyalty to the Union, while the rank of colonel was a reward for the loyalty of these more junior officers.

Analysis of the pre-war careers of those officers who remained loyal to the Union and those officers who resigned their commissions to serve Virginia reveals a noteworthy trend. From the time of their commissioning to the outbreak of the war, Alexander and Cooke saw continuous service far from Virginia, whereas both Fauntleroy and Lee saw breaks in their service during which they were actively integrated into Virginia society.

From the time of his commissioning in 1823, Alexander was only once briefly posted back in proximity to Virginia during a short period of detached duty in Washington D.C. from his assignment at Fort Smith, Arkansas.[8] Cooke spent his pre-war career moving between hotspots, serving in campaigns against the Blackhawk, Apache, and Sioux; the Mexican War; the Utah Expedition; Bleeding Kansas; and serving as an observer of the Crimean War. He summarized his loyalty by stating “I owe Virginia little, my country much.”[9]

The officers who felt that their first duty was to Virginia served there for long stretches of their careers. Fauntleroy was commissioned at age 17 to serve as a lieutenant in the War of 1812. He studied and practiced law after the war and held elected office in Virginia as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. He then returned to active service in the Second Seminole War, after which he continued to serve on the frontier and in the Mexican War. In 1861, he resigned his commission and post in command of the Department of New Mexico. He accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the Provisional Army of Virginia, which he would later resign rather than accept a Confederate commission.[10] Lee served in engineer assignments at Fort Monroe, Virginia and in Washington, D.C. He also saw a break in his service during which he returned to Virginia. When his father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, died in 1857, Lee took a leave of absence to personally run Custis’ Arlington plantation.[11]

This trend suggests that Seidule may have overstated his point. Lee’s actions were not an extreme outlier of behavior when compared to his peers. Those officers who had effectively made the Army their home over three or more decades chose to remain loyal to the Union, while those officers who retained close ties to Virginia chose to serve Virginia following secession. This trend is paralleled among other ranks. Of the two generals from Virginia in the pre-war Army, Winfield Scott chose to remain loyal while Joseph Johnston resigned to serve the Confederacy.[12] This trend is not surprising. These men took oaths at a time when there was no conflict of interest between their loyalties to their state and their country. When faced with a crisis of loyalty, several of these men who had provided decades of service to their country still felt that they could not take up arms against their home state. Whether Lee was a traitor for doing so is outside of the scope of this analysis, but Lee’s behavior does not appear as anomalous as Seidule suggests.

————

Collin Hayward is a qualified Army Historian. He holds a Bachelor’s degree from Virginia Tech and Master’s degrees from American University and the Army Command and Staff College.

Endnotes:

[1] Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2022), 226.

[2] “If Virginia Stands by the Old Union’ – Robert E. Lee Resigns from the U.S. Army – Richmond National Battlefield Park (U.S. National Park Service),” (U.S. National Park Service), June 6, 2025, www-nps-gov.translate.goog/rich/learn/historyculture/-if-virginia-stands-by-the-old-union-robert-e-lee-resigns-from-the-u-s-army.htm;

[3] Seidule, 223; Official Army Register for 1861, (Washington D.C.: Adjutant General’s Office, 1861), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433008010542&seq=7&q1=rene, 9.: “If Virginia Stands by the Old Union”.

[4] “If Virginia Stands by the Old Union”.

[5] “If Virginia Stands by the Old Union”.

[6] “Thomas Turner Fautleroy,” Arthur J. Morris Law Library, accessed October 29, 2025, https://digitalhistory.law.virginia.edu/person/thomas-turner-fauntleroy.

[7] Edwin C. Bearss, “Philip St. George Cooke (1809–1895),” Encyclopedia Virginia, December 22, 2021, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/cooke-philip-st-george-1809-1895.

[8] George W. Cullum, “Edmund B. Alexander,” essay, in Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from Its Establishment in 1802 to 1890 with the Early History of the United States Military Academy, 3rd ed. (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1891), https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Army/USMA/Cullums_Register/358*.html.

[9] Bearss.

[10] “Thomas Turner Fauntleroy”.

[11] Elizabeth Brown Pryor, “Robert E. Lee (1807–1870),” Encyclopedia Virginia, February 18, 2025, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/lee-robert-e-1807-1870.

[12] “If Virginia Stands by the Old Union”.

Excellent analysis. Extra scrutiny is warranted in Civil War writing. Unfortunately, bias is everywhere.

It’s always good to add nuance to sweeping claims, but you’ve just proved Seidule’s point, I think. The only example you came come up with is COL Fauntleroy and not even he served on active duty with the Confederate army. It seems like Seidule’s general is valid: Lee’s service with the rebel army was anomalous and justly seen as such at the time.

I think this article convincingly demonstrates that Seidule’s statement that Lee was an anomaly is at least somewhat misleading. From what he said–that Lee was the only colonel from Virginia to join the Confederacy–you would never guess that another Virginia colonel–Fauntleroy–planned on doing so as well, and while he ended up not fighting for the Confederacy, this was for reasons that did not involve objecting to secession or the Confederate cause. Also, to someone who knows nothing about these colonels, Seidule’s statement could easily be interpreted as meaning that all of the men except Lee actively fought for the Union during the war. Again, the article demonstrates that it would be misleading to say that.

Additionally, as others have suggested in the comments, Seidule’s focus on Virginia colonels leaves him open to charges of selection bias, intentional or not.

Lee, the focus in Seidule’s book is on Lee’s supposedly noble loyalty TO VIRGINIA. The comparison to other Virginian colonels is entirely appropriate. It’s context. Seidule’s point is clear, and proven by this article. When you boil it down, Lee was an anomaly among Virginia Colonels. Period. None of the others chose the same path as him.

Yep, he proved Seidule’s point precisely.

Nice essay, thanks!

But it got me thinking … if you are looking to bash R.E. Lee, the strongest argument you can make is he broke his oath of office — which is still a HUGE deal … you can call him a traitor till the cows come home, but Lee was not tried for treason … i.e., not a traitor.

And I don’t think singling out Lee for an extra helping of scorn is very interesting … although it no doubt sells books (good for Prof. Seidule) … the far more intriguing question comes when you look across the entire army colonel/navy captain cohort, from all southern states and not just VA … of that larger cohort, 17 percent resigned … that includes Joe Johnston who was a general officer … 17 percent is still a small number, but it is not an anomaly.

The more thought-provoking question is why relatively few senior officers resigned when compared with the total of all southern officers who resigned — that is about 64 percent — big number … perhaps for the much older senior guys it was loyalty to the nation … others may have been sympathetic to the south, but were too old, too fat, too infirmed, or too comfortable looking ahead to their retirement and pensions.

This is an excellent point. It is still stressed to Officers today that if you disagree with a policy, you always have the right to resign your commission. Whether or not Officers who resigned pursued Confederate or state commissions, the sheer number of resignations demonstrates how few senior Officers were comfortable with navigating this crisis of loyalty.

You also raise a good point when you cite the relatively small sample size. The pre-war Army is already a very small population, so depending on how you decide to sample, one can easily present biased data sets. For example, if assessing Generals from Virginia, 50% chose to side with the South. By assessing all Officers from Virginia, you’d get a very different number, as you would by assessing all Officers from Southern states, etc.

Confederates were pardoned… for treason… read the pardon announcement.

John,

i did read the announcement — Grant did not pardon anyone, that’s a legal act of forgiveness that only the President can issue … as part of the surrender terms, Grant issued a parole which was significantly different … a pardon wipes away a crime, the parole simply said “We will not bother you as long as you go home and behave.” … however, the operative phrase which provided some protection for Lee was the last sentence: ” … each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.”

The phrase ” … not to be disturbed by United States authority … ” immunized Lee and his officers against treason charge … so, when Grant got word that Sec Stanton was comtemplating charging Lee and others with treason, Grant threatened to resign … Grant argued that his word was given at Appomattox, and if the government arrested Lee, they would be violating the military terms of surrender … Grant’s “parole” won the day, Stanton dropped the matter, and Lee was never tried, although he could have been.

Thoughtful and well-written article; but I concur with Mark above; I believe that you have proven Seidule’s point. What Lee did was wrong; he broke his oath and however much we may like/dislike looking at that fact of history; a fact of history it yet remains.

Mark, the Civil War has a way of provoking strong reactions, whether in regards to slavery, loyalty to country vs home, the natural right to revolution, etc.

For this reason, I tried to steer this article away from any discussion of right and wrong and merely towards an analysis of fact. Of the Virginia colonels serving at the time of secession, roughly half of those capable of commanding troops in the field chose to resign their commissions to serve their state. Lee might well have been wrong for doing so, but he was not the extreme outlier that Seidule suggests.

Is resigning a commission, which officer were allowed to do, breaking an oath?

You asked the $64,000 question … I could write several thousand words on the officer’s oath—its history, its philosophy, and its legal standing—but here is the bottom line on why resigning a commission does not relieve an officer from the obligation they swore to uphold.

Resignation is an administrative act, not a moral reset … while resignation legally releases you from the duties, privileges, and powers of the “office,” it does not release you from the moral obligation of the oath you swore …. there is simply no mechanism for military officers to “unswear” a promise of allegiance.

Consider the text Robert E. Lee swore: to “bear true allegiance to the United States of America” and to “observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States.” … despite his resignation, Lee violated this oath … while leaving the service legally released him from the requirement to obey the President, it did not absolve him of his pledge of “true allegiance.” … this principle was confirmed in the 14th Amendment, which disqualified from public office those who “having previously taken an oath,” and later engaged in insurrection.

Congress later “tightened up” the oath that military officers take today … by removing the pledge to “obey the President” and explicitly adding “domestic enemies” and “no mental reservation,” the modern oath eliminates any ambiguity … it clarifies that while an officer may voluntarily lay down their rank (and the chain of command that binds them to the President), they can never lay down their loyalty to the Constitution.

Great entry, Collin! I find Lee’s motivations for resigning his commission and ultimately joining the Confederacy to be utterly fascinating. He’s come under a lot of flack in the last few decades, but I think pursuing this question (and his motivations) adds much more nuance and complexity to his character.