“Scared Ol’ Abe Like Hell”: The Battle of Fort Stevens

They were not much to look at: a ragtag, dust caked, mostly shoe-less, begrimed bunch of tanned soldiers carrying rifles and shuffling toward Washington D.C.

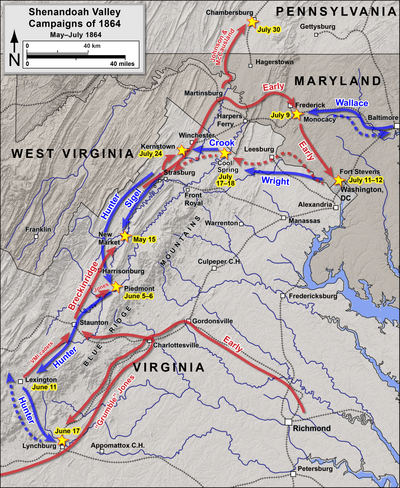

But, they represented a big threat. Especially in the summer of 1864. They were not supposed to be in Maryland much less approaching the nations’ capital. Yet, Confederate General Jubal A. Early and approximately 10,000 soldiers were filtering into lines 150 years ago today, on July 11th, near Silver Spring, northwest of Washington D.C.

Fortune smiled on the Union on this day though. Intense heat along with the weariness of fighting a pitched battle along the banks of the Monocacy River near Frederick, Maryland that lasted all day on July 9th had fatigued Early’s army. “Old Jube” as the Confederate commander was known to some, was also unsure of the forces guarding the approaches–including the impressive array of entrenchments, redoubts, and forts around Washington D.C.

The Virginian called a halt to do some reconnaissance.

And those three things; heat, the Battle of Monocacy, and time needed for surveying the enemy lines saved the nation’s capital.

Early’s forces would begin to skirmish with the Union forces holding Fort Stevens in the mid-afternoon. At approximately the same time–3 p.m.–arriving on the wharves along the Potomac River was elements of the Union VI Corps sent up from the Richmond-Petersburg front. Commanded by Major General Horatio Wright, these veterans of over three years of combat against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia would head directly to the front.

As these Union reinforcements arrived near the front; so did another few persons. This reinforcement was of a different variety though. Strolling into the fort was the chief executive of the Union war effort, President Abraham Lincoln. (There is some confusion about what date the president came to the fort but he was present either on July 11 or 12 regardless). He became the second sitting United States president to be shot at by enemy forces in time of war.

Supposedly, an officer, Horatio Wright or Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. the author of the account, brusquely told the lanky, tall, former “railsplitter” Lincoln to take cover. A Union surgeon standing near the president was wounded by Confederate sniper fire.

With this going on behind the Union lines, the Confederates had increased their pressure on the front of those same lines. Near 5 p.m. Confederate cavalry was able to temporarily breach Union skirmish lines as Confederate infantry applied greater pressure against the front-line blue-clad soldiers around Fort Stevens.

These efforts were turned back when troops of the garrison of Washington D.C; the XXII Corps and the action filtered out shortly thereafter.

As dawn approached on July 12, Early could plainly see that Union reinforcements crowned the Washington D.C. defenses. As skirmishing continued throughout July 12, Early realized that the it would be suicidal to launch his meager forces against strong earthworks and numerically superior Union forces.

Waiting until dark, Early began to pull his forces away from Washington D.C. and head northwest, crossing over the Potomac River at White’s Ferry on July 13th. His invasion of Maryland was over, but the trouble of catching “Lee’s Bad Old Man” as Early was also known as, was just beginning.

That story would continue until late October. But, for now, Jubal Anderson Early, the commander of the Second Corps Army of Northern Virginia or the reconstituted Army of the Valley, had in his own words;

“Scared Ol’ Abe like hell.”

The Union would have to respond to eliminate rebel forces from ever doing this again…..

*To follow the history of what happened after the Monocacy-Fort Stevens-Maryland Invasion of the summer of 1864, check out “Bloody Autumn; The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864” part of the Emerging Civil War Series.*

**Fort Stevens is now preserved by the National Park Service. To plan a visit, please consult www.nps.goc/rocr **