Reynolds Reconsidered

Was John Fulton Reynolds a great corps commander? Was Reynolds even a great general? And why do Civil War buffs have such a high regard for an officer who did so little in the Civil War compared to the likes of Stonewall Jackson, George Meade, Robert E. Lee, or Ulysses S. Grant? While these questions have lingered in my mind, I have taken the opportunity to question the cult of Reynolds in writing and during battlefield tours. Reactions to my queries have elicited some curious responses. One person challenged that a good Civil War general should always lead from the front. To which I responded a dead general only benefits the enemy—unless that general is Braxton Bragg. Another respondent, angry that the subject was even broached, compared Reynolds leadership to that of George S. Patton, Jr. Comparing Patton to Reynolds is foolish, as one of the generals helped to drive the Wehrmacht across Europe while the other could rarely seize or hold an assigned position. Yet another person asked the question “Was Reynolds narcoleptic?” Since Reynolds seemed to fall asleep during key moments of his career, and nearly overslept the opening of the Battle of Fredericksburg—had he not been saved by late arriving orders from Army of the Potomac headquarters. Questioning assumptions is the job of the historian, and it is not the dreaded or derided revisionist approach to history. Rather, when there is a dearth of facts backing up a claim, one should question the preconceived notions surrounding a subject. And these preconceived notions surrounding Reynolds have lingered in my mind.

Major General John Fulton Reynolds was a solider through and through, and that should not be forgotten in any assessment of the man and the officer. Still, he was only truly tested once as a corps commander, that being at the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg. Prior to Fredericksburg, Reynolds Civil War fighting record was solid, but nothing one would call stellar. Gettysburg historian Edwin Coddington claimed “He [Reynolds] was a first class fighting man, universally respected and admired. If the fates had decreed other than they did, he might have gone down in history as one of the greatest generals of the Civil War.”[1] While, Reynolds was universally respected and admired, the rest of the statement seems to have taken shape in the minds of many in the Gettysburg circle—Reynolds being considered one of the greatest generals of the Civil War. Outside of the Battle of Gettysburg, Reynolds name rarely comes up although he saw action on the Peninsula, at Second Manassas, and at Fredericksburg. Yet, it seems, that many Civil War buffs only have the perception of John Reynolds boldly seated atop his charger leading the Iron Brigade into Herbst Woods taking decisive action in America’s most famous battle. That lone moment, that lone action fuels the perception of Reynolds while propelling him onto a list of officers that leave us want more—Stonewall Jackson, Albert S. Johnston, James B. McPherson—officers who met an untimely demise. Leaving many to ask what could have been if… Historian D. Scott Hartwig stated, “What seems to have impressed people about Reynolds was not his combat record but his competence.”[2] Perhaps this is the case for those who have taken the time to look more deeply into the story of John F. Reynolds, but it doesn’t seem to be the case for the slew of armchair historians. One armchair historian called referred to him as a “Rockstar.,” and another called him exceptional.[3]

John Reynolds was born into a large and fairly well connected family in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on September 21, 1820. Pennsylvania senator and future United States president James Buchannan nominated young John for acceptance to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Reynolds graduated four years later in the middle (26 out of 52 cadets) of the West Point class of 1841. His class included a laundry list of future Civil War generals, many of whom lost their lives in combat—Amiel Whipple, Nathaniel Lyon, Robert S. Garnett, Richard S. Garnett, and Israel Richardson—and of course Reynolds himself. After graduation, he served in the artillery and was brevetted twice for bravery in the Mexican-American War. By 1860, he found himself back on the Hudson River as commandant of cadets at West Point, and serving as a tactics instructor at his alma mater.

Reynolds began his Civil War career with the 14th United States Infantry before being promoted to brigadier general and transferred to brigade command in the Pennsylvania Reserves. In the spring of 1862, Reynolds and his men were stationed in Fredericksburg, Virginia, as part of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s I Corps in the Army of the Potomac. For a brief period, the Pennsylvanian served as the military governor of the city. While the locals largely loathed their Yankee overlords, Reynolds was found to be a stern but fair military governor.

On the Peninsula, in June of 1862, Reynolds fought his brigade at Beaver Dam Creek and Gaines’s Mill. After the latter action, Reynolds was captured by Confederate soldiers. There are a few versions of the General’s capture. According to John Reynolds himself,

“I went with my Adj. Gen. [Capt. Charles Kingsbury] to the right of the line to post the artillery…where I remained till nearly dark, when in endeavoring to return to my brigade, I found the left of our line had given way and Confederate pickets occupying the ground I had passed over, and taking what I thought [to be] a direct course through the woods to our rear, became entangled in the [Boatswain’s] swamp with my horse wounded, and unable to extricate him, I remained there through the night, and when day broke made another effort to regain the position of our lines, but was unfortunately unsuccessful and taken prisoner.”[4]

Historian Brian K. Burton states that Reynolds was captured by members of the 4th Virginia Infantry of the famed Stonewall Brigade.[5]

Some of Reynolds Confederate captors tell a different story. According to historian Stephen W. Sears, “Exhausted after two days of continuous duty, Reynolds had thought to catch some sleep in a supposedly secure pace and was overlooked in the retreat, and the next morning was awakened by some of D[aniel]. H[arvey]. Hill’s men.”[6] According to one post war account Hill went to visit his friend from the Old Army after Reynolds capture. Hill said “Reynolds, do not feel so bad about your capture; it is the fate of war.” To which Reynolds supposedly responded, “It is not being captured…that hurts so, but it is being captured asleep.”[7]

Was Reynolds trying to write off an embarrassing situation in his letter home to his sister? Or was the D. H. Hill story apocryphal, as Hill was selling war stories to a well-paying publishing house? The true story probably lies in between the various accounts. Still, I often wonder how a general officer gets misplaced in the action and gets left behind on the field…asleep.

Reynolds was then sent to Libby Prison, where he was held in captivity with fellow Brig. Gen. George A. McCall, and 13 field officers—including Lt. Col. Samuel M. Jackson of the 11th Pennsylvania Reserves—the maternal grandfather of the actor Jimmy Stewart.[8] Reynolds and his fellow Union soldiers were treated poorly by Brig. Gen. John A. Winder, the commandant of Libby Prison, “was disposed to take his revenge out as our jailor,” claimed Reynolds, who, would not name the “officer who was formerly at West Point under me and guilty of very dishonorable conduct so that I would not speak to him.”[9] Other Southern sympathizers treated the captured general better. Fredericksburg Mayor Montgomery Slaughter and prominent citizen John Marye traveled to Richmond with a petition from the people of Fredericksburg “asking in return for Gen. Reynolds’ kindness that he might be paroled.”[10]

Following his exchange Reynolds took command of the Pennsylvania Reserves division. He showed great personal bravery at Second Manassas and he commanded his division with skill, as orders and counter orders called upon the Keystone State soldiers to march all over the field. The Pennsylvania Reserves absorbed much of the Confederate onslaught on August 30th. As the southern steamroller took aim at Henry House Hill, Col. Henry Benning’s brigade exposed their flank to one of Reynolds brigades. Leading by example, Reynolds on foot, seized the flag of the 2nd Pennsylvania Reserves and led the balance of Brig. Gen. George G. Meade’s brigade into the Georgians flank. This was great act of bravery, but he took himself from a division commander to essentially a regimental commander by his actions. This was the second battle in a row that Reynolds essentially demoted himself. at Gaines’ Mill he was separated from his command when he went off to position a battery—which was the job of a staff officer or battery commander.

Post-Second Manassas Reynolds went to Pennsylvania and assumed command of the state troops massing for the Antietam Campaign. When Reynolds returned to the Army of the Potomac, he assumed command of I Corps. The corps was made up of some of the best units in the army, and many were led by excellent brigade and division commanders such as John Gibbon, Lysander Cutler, and George Meade.

At Fredericksburg, on December 13th, Reynolds corps broke through at Prospect Hill. This was the only Federal breakthrough at Fredericksburg. In reality, Reynolds had little to do with the breakthrough itself, he actually had more to do with the hindering his subordinates short lived gains. Reynolds did not act as a corps commander at Fredericksburg. When both Meade (now a major general) and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s divisions broke the Southern lines at Fredericksburg, they could not receive timely reinforcements. Their corps commander could not be located. Meade sent a number of messengers to Reynolds begging for reinforcements, none could locate him.

Their corps commander was on the Federal artillery line. He was personally ordering batteries where to fire, how to elevate, and according to some accounts, at times was off his horse sighting guns himself. This was not the job of a major general, it was the job of Colonel Charles Wainwright, the 1st Corps Chief of Artillery. “He [Reynolds] is an old light-artillery captain, and ought to know how to take care of his artillery,” penned Wainwright in a September 1862 diary entry.[11] Now in his first battle as a corps commander, Reynolds was taking care of his artillery. Too good of care in fact. Reynolds demoted himself from a corps commander to an artillery battalion commander, and did so at the times his subordinates needed him the most. Fredericksburg historian Francis A. O’Reilly states “A close search of the records reveals that Reynolds spent most of his time worrying the artillery about ephemeral details rather than monitoring the overall situation.” O’Reilly goes on to say, “At one time or another, every battery in the First Corps encountered, received advice from, or took orders from Reynolds….[which] made him completely ineffective when Meade sought critical reinforcements.”

Reynolds allowed the minutia of command to get in the way of him doing his job on and off of the battlefield. Charles Wainwright noted an incident. “While we were waiting Reynolds shewed me a trait in his character which is to a certain extent commendable, but not always agreeable to others,” recalled Wainwright.

“He sent for me and desired me to send an order around to the battery commanders to feed up any hay they might have over, while they were waiting; instead of leaving it behind. A very right and wise thing for them to do; but this giving of orders about little things on the part of a corps commander is a sort of reflection on the ability of the subordinate, to whom he gives them, to understand and attend to his own business. I should have thought it an insult to my battery commanders to send such an order around to them…It is a great mistake not to place confidence in those under you. Well enough to keep an eye on them until you know they are competent; but if you are interfering in every little matter they will never have confidence in themselves…”[12]

During the Chancellorsville Campaign, the I Corps did a great deal of marching and very little fighting. In fact, of the 16,908 men that Reynolds fielded during the campaign, less than 300 were listed among the casualty lists at the end of battle. During the riverine crossing at Second Fredericksburg, Brig. Gen. James Wadsworth led part of the famed Iron Brigade across the river and forced a landing, which was a much heavier task than it should have been, since Reynolds did little to coordinate his efforts with another crossing force up the Rappahannock River. The I Corps was part of a larger task force which included the I, III, VI Corps, as well as elements of II Corps and the Artillery Reserve. While the force was commanded by Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, who had no experience as a corps commander let alone the experience to command a wind of an army, neither Sedgwick nor Reynolds coordinated their riverine crossing of the Rappahannock River. Following the crossing, I Corps was called from Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville, but were held in the rear echelon of the army for much of the battle. During a council of war among the Federal high command, which was to decide if the army was to stay and fight it out or retreat, Reynolds fell asleep…again. One person has defended Reynolds sleeping during the council of war, since he sent a proxy with his vote to stay and fight. The proxy was the 5th ranking general officer in the army at the time. Shouldn’t Reynolds, one of the most looked up to and experienced officers in the army, stay awake for this all important meeting and argue the case to stay and fight it out? Where was the leadership of this “Rockstar?” At this point of the campaign, the I Corps had seen very little action, and not enough action to fatigue Reynolds so much that he could not attend the meeting while other senior officers, who had been in sustained action for days, had the stamina to attend the meeting and advocate for their respective votes.

After Chancellorsville, the Union high command was in turmoil. Many senior officers did not want to serve under their commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who, had just lost the Battle of Chancellorsville and the confidence of the army. On June 2, 1863, Reynolds met with President Abraham Lincoln. While the substance of the conversation has been lost to the pages of history, the popular belief is the Lincoln offered Reynolds command of the Army of the Potomac. Outside of secondhand accounts we cannot verify or deny this claim. While Reynolds was one of the senior officers in the army, it is conceivable that he was offered the command. We do know that during the latter stages of the Gettysburg Campaign, Reynolds was promoted to command the Left Wing of the Army of the Potomac by George G. Meade. The Left Wing consisted of the I, III, XI Corps, and Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry division. It was while acting as a wing commander, where he oversaw fully one-third of Meade’s cavalry, and nearly one-half of the infantry in the Army of the Potomac, Reynolds was killed. At the time of his death was actually acting at best like a brigade commander, at worst a regimental commander as he moved forward with the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry of the famed Iron Brigade. While Buford’s cavalry was being pushed back by superior Confederate forces, the fact that Reynolds took to the field as a regimental commander rather than a corps or wing commander hampered the Union fight on July 1. His subsequent death therefore boosted XI Corps commander Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard to command the Federal troops on the field. even the stoic John Buford was moved to send to army headquarters for help. “For God’s sake,” Buford is said to have told Meade, “send up Hancock. Everything is going at odds. Reynolds is killed and we need a controlling spirit.”[13]

The great issue that I have with Reynolds as a commander is that he rarely acted the rank that he held. At Gaines’s Mill he was acting as an aide or battery commander at best. At Fredericksburg he was not where he was needed-in the rear in an easy to find place for his subordinates and assisting with gaining reinforcements and driving Stonewall Jackson from the field. Rather, he was acting as an artillery battalion commander. And at Gettysburg he acted as a brigade commander at best, and a regimental commander at worst. At Gettysburg he was a wing commander, and he should have been nowhere near the main battle line. The closest spot to action he should have been would be the cupola of Lutheran Theological Seminary. Even the vapid Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard knew that he needed to be in an easily recognizable place, nowhere near the front lines, easily found by the men when he assumed Reynolds role. (That is not to say that Howard did not make many mistakes of his own). On top of all of this to me Reynolds did not choose the ground to fight on at Gettysburg, John Buford did. Yet today Reynolds role greatly overshadows those of Buford, William Gamble, Abner Doubleday, and a slew of Union officers who recognized the importance of the ground at and around Gettysburg and then fought tenaciously to hold that ground. It was Buford that defended the approaches to Gettysburg on the evening of June 30, 1863, and who initiated contact with the enemy. In fact, Reynolds did not expect a fight at Gettysburg or on July 1. “I rode on ahead to learn what I could as to the prospects of a fight,” recalled Charles Wainwright, “I saw General Reynolds, who said that he did not expect any: that we were only moving up to be within supporting distance to Buford…”[14]

After his death Reynolds was treated as a hero. Much of this was not because of Reynolds actions, but the actions of his staff and others. Alfred Waud produced a famous sketch of his death. Reynolds death itself came at the height of a major Union crisis, where he was felled on home soil. Some of the accounts written by his staff were not so much written to glorify Reynolds, but written to garner favor from Reynolds family and friends, while living in the shadow of a now nationally famous officer. And Then of course there are the slew of monuments that were erected by the survivors of the corps and others that recalled the bravery of their commander of the old I Corps, a corps that was eliminated by

As a leader of men there is no doubt that Reynolds was brave to a fault, and respected as an officer for his fairness to soldiers and civilians alike. He respected the enemy, so much so that Reynolds sent back a captured Rebel who was trading with New Jersey troops on the Rappahannock River in May of 1863. The Federal pickets invited the man across the river to trade, which was a common practice on both sides, but then the Yankees captured the man and took him to Reynolds, who, told them “that was not honest to lie or deceive [the enemy] in that way.”[15] The New Jersey soldiers released the man shortly thereafter, and they received harassing fire from thence forward whenever any New Jersey unit manned the Rappahannock picket line.

In the end, the problem with his command style and bravery was that they took Reynolds from brigade, division, corps, and wing commander down to a regimental commander, battery or battalion commander at the height of great crisis. And at the greatest moment of crisis, at Gettysburg, Reynolds was in the wrong place at the wrong time—not through the fault of others—but through the fault of Reynolds himself.

One has to ask themselves… Was Major General John F. Reynolds a great general, or was he just killed at the right place at the right time?

[1] Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1984), 37.

[2] D. Scott Hartwig, “John Reynolds Recklessness Shaped Victory at Gettysburg,” History Net, last modified September 2019, https://www.historynet.com/john-reynolds-recklessness-shaped-victory-at-gettysburg.htm.

[3] Civil War Fan Girl, “Union Rock Stars: Major General John Fulton Reynolds” Civil War Fan Girl (blog), June 13, 2016, https://cwfangirl.wordpress.com/2016/06/13/union-rock-stars-major-general-john-fulton-reynolds/. Kristopher D. White, “Reynolds Reconsidered,” Emerging Civil War (blog), July 1, 2012, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2012/07/01/reynolds-reconsidered/#comments; comments section of September 23, 2018.

[4] John F. Reynolds to Eleanor Reynolds, Letter, July 3, 1862 Reynolds Family Paper Collection, Franklin & Marshall College.

[5] Brian K. Burton, Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles (Bloomington, IN.: Indiana University Press, 2001), 154. Historian James I. “Bud” Robertson, Jr., notes in his work The Stonewall Brigade (page 120), that the brigade captured Reynolds but does not explicitly state the circumstances surrounding the capture of Reynolds.

[6] Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1992), 252.

[7] Article in the Jed Hotchkiss Papers, Library of Congress, Reel 59; Frame 314. Hill also retold the tale of taking his old West Point Classmate in the popular post war series Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

[8] Samuel M. Jackson Diary entry of July 5, 1862, The Diary of General S. M. Jackson 1862, in the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Bound Manuscript Collection.

[9] John F. Reynolds to Sister, Letter, August 15, 1862 Reynolds Family Paper Collection, Franklin & Marshall College

[10] Lizzie Alsop diary entry of July 14, 1862, in the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Bound Manuscript Collection.

[11] Charles S. Wainwright, A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865, ed. Allan Nevins (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998), 108. Diary entry of September 30, 1862.

[12] Ibid., 218. Diary entry of June 7, 1863.

[13] Michael Phipps, The Devil’s to Pay: General John Buford, U.S.A. (Gettysburg, PA.: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1994), 52.

[14] Wainwright, A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865, 232. Diary entry of July 1, 1863.

[15] Horace Currier letter dated May 29, 1863, in the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Bound Manuscript Collection.

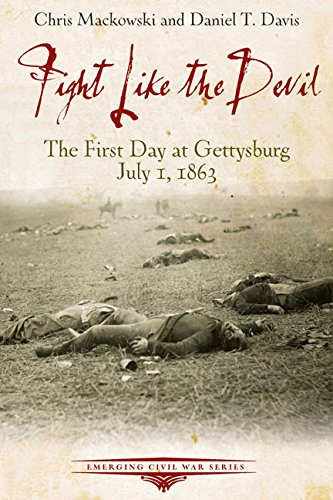

Be sure to check out Fight Like the Devil: The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863; authored by Chris Mackowski, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis.

Years ago I quoted at length what Wainwright had to say about Reynolds’ death. There, i said triumphantly, that shows what happened!! And a blogger friend, who had actually read Wainwright’s original journal, told me Nevin’s edited edition was actually written well after the war. What Wainwright actually wrote was along the lines of “Went to Gettysburg, Reynolds killed, left Gettysburg.” So much for first hand accounts!

Bob,

Your comment reminds me if the Life and Letters of George G. Meade, which were thoroughly edited by George Jr. before they went to press.

Kristopher,

Love the article. The answer might be that will never know. The other question was why wasn’t he name commander of the Army of the Potomac after Hooker resigns? One of the first things Meade does after being woke by a War Dept. administrator outside Frederick,MD informing him of his new position, (Meade actually thought he was being arrested) he goes to Reynolds to tell him he should be put in charge as senior officer. Reynolds assures Meade the War Dept. made the right decision and he has all the confidence in Meade to lead the Army of Potomac. and supports him. Well we know this turned out pretty well. Meade defeats Lee, immortalizing him (don’t ask Sickles this) and Reynolds is killed and immortalized him. I know it doesn’t make him a great Corp Commander but he’ll gets him a really nice big equestrian statue on the Gettysburg Battlefield.

Tim,

Thank you for the kind remark. To your question about why Reynolds wasn’t named commander of the AoP.

Post Chancellorsville, most of the corps commanders within the high command were done with Hooker. His pre-war reputation, combined with his bragging on the outset of the Cville Campaign, mixed with his finger pointing when he screwed the pooch was too much for them. The most outspoken opponent of Hooker was Slocum, who along with Couch and Sedgwick, were the ranking corps commanders within the army.

In the days following Chancellorsville some of the generals, especially Slocum, seemed to be in open revolt against Hooker, who, unlike Burnside, refused to be a man and stand up for the mistakes he made.

Lincoln had given Hooker plenty of freedom with the army, a rope with which Hooker hung himself as a commander. In the weeks following Cville, Lincoln started pulling in that rope and closed the direct line of access to the Executive Mansion that Hooker had enjoyed. Now Hooker had to go through Halleck, and they both loathed one another.

When the politicians arrived in the camps after the battle of Cville, most of the high ranking officers told them that Hooker had to go. When asked who to replace him with most of them sidestepped the question and pointed directly at Meade. While they had a great deal of confidence in him, the truth of the matter was that only two men had really been crazy or self-centered enough to want the command, they being Hooker and McClellan.

Couch left the army, Slocum and Sedgwick both turned it down cold when the matter came up. Sedgwick was more than happy being a corps commander, and Slocum didn’t want the headache of Hooker’s doings. Hancock’s name was kicked around, but he had just been elevated to 2nd Corps command when Couch left and was the junior ranking corps commander in the army. Reynolds, was brought to Washington on June 2nd, the day before Lee opened the campaign, and had a lengthy meeting with Lincoln. Essentially Reynolds pulled a Joe Hooker on Abe. He told him what was wrong with the current commander and that he had to go (something Hooker had done to Burnside in a round about way). Then Reynolds basically told the administration that they needed to stay out of the way of the next commander, which Lincoln had done for Hooker. He also told Lincoln that he did not want to deal with “Burnside’s and Hooker’s leavings.” If you read between the lines on that you will see what he meant. Reynolds then did what everyone else was doing and pointed to George Meade to be the next commander. Lincoln seems to have been taken aback by Reynolds Joe Hooker like approach and tabled the conversation by saying he “was not disposed to throw away the a gun because it misfired once…he would pick the lock and try it again.” Meaning old Joe would get another crack at it. the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t know.

As the two armies came close to blows in late June, Halleck baited Hooker. Hooker offered to resign, and the rest of that is history.

George Meade, the one guy that actually seemed to have Hooker’s back through it all, got Hooker’s job, due to the recommendations of his peers and the fact that nobody else wanted the job. Mind you, Meade had his misgivings, and if his edited letters are accurate, he didn’t want the job, nor did he lose ALL confidence in Hooker, as the majority of the senior command had..

Excellent post. It enlightened me as I’m researching a historical novel where Reynolds plays a very minor role. I was curious about the portion where you mentioned his staff may have glorified him in order to curry favor with higher ups due to a staff officer being brought up on rape charges. As a fiction writer I was intrigued by the tidbit and wondered where you read about that incident. Thanks!

Excellent post! Very enlightening as I enjoyed the varying viewpoint. I stumbled on your article while doing research on Reynolds as he plays a minor role in my historical fiction novel. I was curious mostly as a writer as you mentioned his staff glorified him most likely to curry favor with

his friends/family because one of his officers was accused of rape. I never found that story while doing my research, where did you read about that incident? Thanks!

Your point well taken. McPherson’s Ridge involves a case in extremis. Only with Reynolds’ aggressive leadership did the first troopers to arrive go double-quick across the fields to bolster a fading Buford. While at Gettysburg, I invisioned it: the gallant general racing across the field, bypassing the village, to the far ridge. No other rank could have effectuated it so quickly.

I disagree with your assessment here.. In short, Reynolds was an exceptional General and yes, corps commander who believed men are to be lead by their commander and not simply driven forward into the fire while while he hides at his men’s backs. You said that “During a council of war among the Federal high command, which was to decide if the army was to stay and fight it out or retreat, Reynolds fell asleep…again.” No, he did not simply ‘ fall asleep’ and neglect to contribute his views on providing Hooker’s requested votes on whether to attack or retreat. That’s all it was. Before retiring to his corner of the room the commanders would collectively be sleeping in, Reynolds appointed Meade as his proxy and instructed him to vote to stay and go on the offensive. Which was Meade’s opinion as well. There are far too many facts and a great deal of details and information omitted/overlooked in your explanation of your reassessment. James Robertson and countless other celebrated historians declared Reynolds the best General in the Union Army. That’s not a opinion reached lightly. If anything, I believe Reynolds was underutilized prior to Jesse’s appointment and was just then truly getting the chance to fully display his immense capabilities as Corps Commander when his life was cut short. I am sorry we didn’t get to see how incredible he would have been when he was finally given the chance to shine by George Meade who knew him intimately, and obviously well aware how valuable and highly effective Reynolds’ leadership abilities were going to be, resulting in his appointing Reynolds command of the army’s left wing. I don’t see what great benefits Reynolds’ staff would garner by lobbying support from his family by dishonestly expressing praise and admiration for their fallen commander. He was beloved by his and his men

whom he was honored by in many ways, including their having erected the most monuments dedicated to any Commander on the Gettysburg battlefield.

Shane,

Thank you for your comment. Clearly I will not sway your opinion. Nor will I waste our time trying to do so. I will simply say that most historians don’t say that Reynolds was the best general in the Union army. Those accolades are normally heaped upon Ulysses S. Grant, the man who won the war. Nor am I the only historian who thinks that Reynolds was overrated. Here is a link to a recent article by Dr. Gary Gallagher. http://www.historynet.com/insight-dying-to-succeed.htm

Hi Shane,

Which work by James Robertson and other historians talk about Reynolds? I’ve long been interested in Reynolds’ career and have read Edward Nichols’ biography on him “Toward Gettysburg.” Also read “Giants in Their Tall Black Hats” essay collection by Alan Nolan and Sharon Vipond. Interesting essay about the Iron Brigade and Reynolds there. Appreciate other insights you can share on Reynolds.

Wonder if General George Patton should have stayed in command centers well behind the front lines during WWII ?……Germans might have won the war