Telling History vs. Making Art: Fictions told until they are believed to be true

Part nine in a series

Part nine in a series

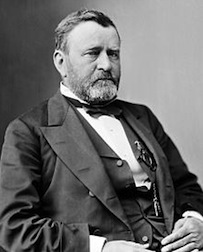

“Wars produce many stories of fiction, some of which are told until they are believed to be true,” Ulysses S. Grant said in his Personal Memoirs.[1]

Grant was specifically referring to a fiction “based on a slight foundation of fact” from Appomattox Court House, where Robert E. Lee’s army surrendered.[2] The formal surrender took place in the home of Wilmer McLean in the heart of the small village, but a legend grew that the surrender actually took place beneath an apple tree. “Like many other stories,” Grant said, “it would be very good if it was only true.”[3] Like a modern game of telephone, where a story evolves in the telling from one person to another, a kernel of fact grew into something totally beyond itself and subsequently became accepted as truth.

“The truth of an account is measured by the conviction the writer builds in the reader’s mind,” Paul Ashdown reminds us.[4] Facts evolve into fictions, and through repetition, become accepted as truths.

In Grant’s mind, facts were “verifiable, quantifiable, recoverable, objective, and rational,” says historian Joan Waugh, and they “could be retrieved from memory, conversations, written reports, letters, maps, telegrams, and diaries.”[5] However, Grant worried about writers and historians who relied too much on those primary sources. Such writers, he believed, “reach conclusions which appear sound…but which are unsound in this, that they know only the dispatches, and nothing of the conversation and other incidents that might have a material effect upon the truth.”[6]

Truth, says Waugh, derives from facts but is not dependent on them.[7] “Truth was subjective and morally based,” she says. “Truth had a higher meaning. Truth was based in the facts but ultimately not answerable to them. Today, professional historians call truth ‘Interpretation.’”[8]

“It is not enough for historians and filmmakers to impart the facts,” says historian Leon Litwack. “It is incumbent upon them to make people feel those facts, to make them see and feel those facts in ways that may be genuinely disturbing.”[9] Artists know this already.

Grant set about writing his memoirs out of financial need, but he also did so because he was genuinely disturbed by the way facts were being interpreted by the growing Lost Cause school of thought. Grant championed the Union Cause. “Thus, the Personal Memoirs were written both to advance a larger truth, that of Union moral superiority, and to remind America of Grant’s contribution to the victory that remade America into ‘a nation of great power and intelligence,’” Waugh says.[10] Grant’s final battle was a war of words over the interpretation of facts, an attempt to advocate a particular truth.[11]

Grant set about writing his memoirs out of financial need, but he also did so because he was genuinely disturbed by the way facts were being interpreted by the growing Lost Cause school of thought. Grant championed the Union Cause. “Thus, the Personal Memoirs were written both to advance a larger truth, that of Union moral superiority, and to remind America of Grant’s contribution to the victory that remade America into ‘a nation of great power and intelligence,’” Waugh says.[10] Grant’s final battle was a war of words over the interpretation of facts, an attempt to advocate a particular truth.[11]

The writer of history, then, faces the same fundamental problem as any other storyteller: What truth am I trying to tell, and how shall I tell it?

The Series Concludes: Fictions and Histories

[1] Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. Library of America, 1990. Pg. 732.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Grant, 735.

[4] Ashdown, Paul. A Cold Mountain Companion. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2004. Pg. 21.

[5] Waugh, Joan. “Ulysses S. Grant, Historian.” Pg. 20

[6] Grant quoted by Joan Waugh in “Ulysses S. Grant, Historian,” pg. 21.

[7] Waugh, 21.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Litwack, 139.

[10] Waugh, 8.

[11] John Guare, author of Six Degrees of Separation, wrote a play about Grant’s memoir writing. “When A Few Stout Individuals opened, the most common reaction I got was, ‘Is this true? This can’t be true. How do you make this stuff up? It’s true?’ I imagined some of it…but you bet it’s all true, except for the tonic salesman, and I know even he existed.” (Guare, John. “Preface.” A Few Stout Individuals. New York: Grove Press, 2003. Pg. xi.)

I have always wondered why Grant does not mention John Rawlins much in his memoirs. He did not attend his funeral. Can anyone give me some info. It would be appreciated.

some of his own rewriting of the truth…