Another Jackson?

In June 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee struck out for another invasion of the north. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia—now organized into three corps—left their lines around Fredericksburg early that same month.

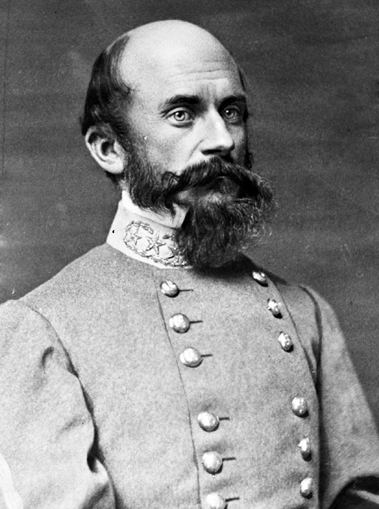

Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, now commanding the Second Corps, led the march northwestward and by the mid-June, his corps was in the Shenandoah Valley and approaching the strategic town of Winchester, Virginia.

Winchester was the key to the lower Shenandoah Valley (geography in the Valley because of the rivers that flow through it is switched from normal directions, going down the Valley a person would be going north and vice versa). The town had changed hands multiple times and well on its way to being commanded by switching hands over 70 times by the end of hostilities.

In June 1863 the town was held by a garrison of approximately 8,000 Union soldiers commanded by the mercurial Major General Robert Milroy. He would be severely outnumbered as Ewell’s Second Corps approached but buoyed by the strong fortifications to the west and north of the town, Milroy elected to stay and fight. He also did not realize until it was too late the force he was about to grapple with. <p> </p>

In doing so, Richard Stoddard Ewell would give credit to Lee for nabbing him to command one of the corps. Likewise, he would orchestrate the Battle of Second Winchester reminiscent of his former late commander; Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

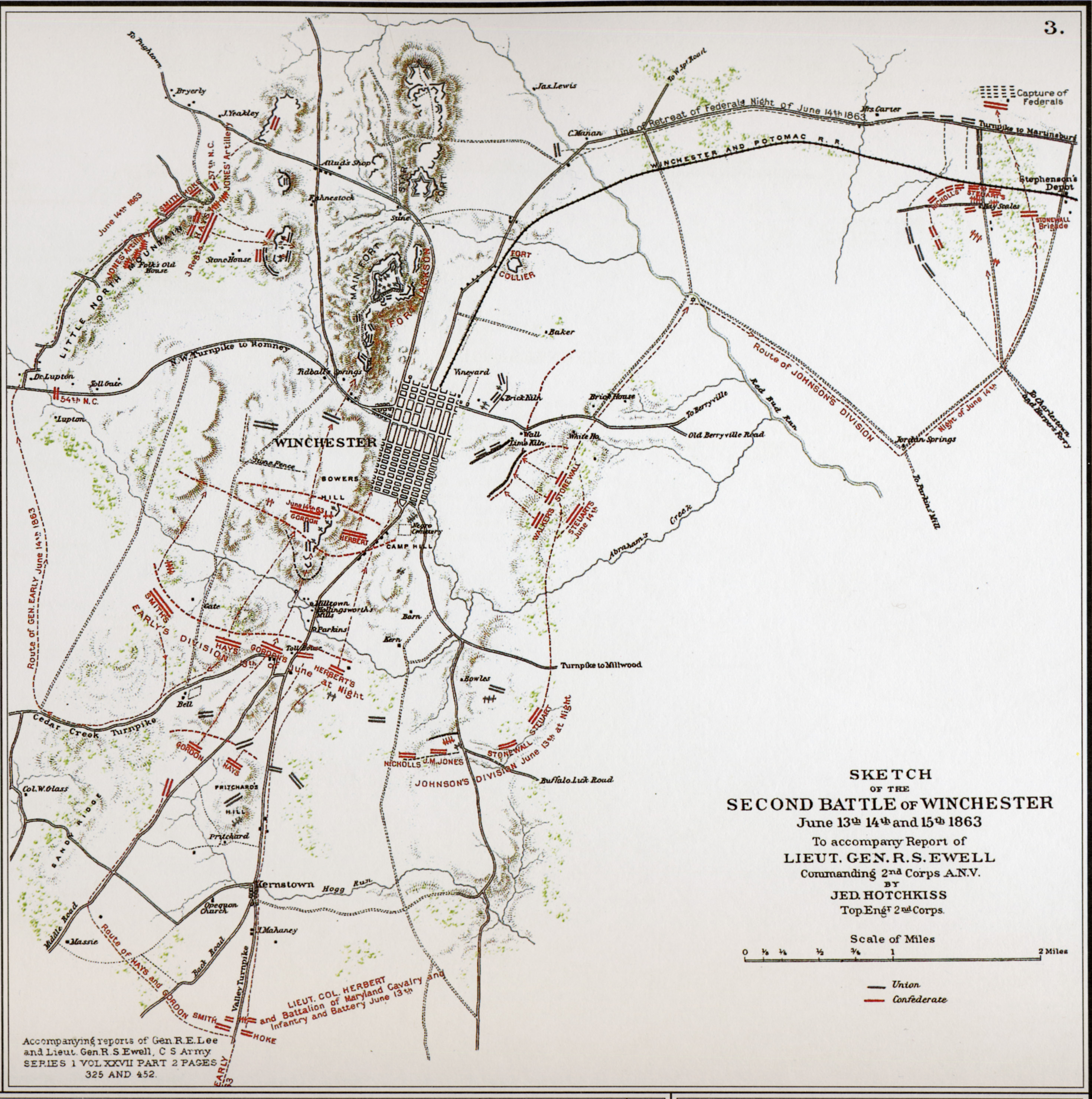

With the approach of the Confederates on Winchester, Milroy consolidated his forces into the a few of the forts and prepared his defense. Ewell, familiar with the terrain, having fought there the previous May at the First Battle of Winchester decided on a pincer movement. Two of his divisions; Major Generals Jubal Early and Edward Johnson would envelop the flanks whereas Major General Robert Rodes’ Division would swing around to Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia) to block the escape route. As June 13th dawned, Ewell’s plan unfolded—the late Jackson would have been proud of his old subordinate.

Units moved out to their designated locations. The Confederate trap of Milroy had begun.

In the pre-dawn hours of June 14th, two brigades from Johnson’s Division; George Steuart’s mixed Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia brigade coupled with Colonel Jessie Williams’ Louisiana Brigade closed in on the Berryville Pike near the town. The “Stonewall” Brigade followed up this advance as Johnson’s Confederate crept toward town and tried to seal off escape routes to the east and eventually the north.

As these brigades moved out, other Confederate units also sprang into action on the 14th. Early’s Division launched their attack to the west of Winchester against West Fort, routing the Federals and capturing numerous pieces of artillery. With the cover of darkness the Union defenders retreated into Fort Milroy and were thus saved from further defeat.

With Johnson’s Division toward the east, Early’s to the west, and Rodes’ operating around Martinsburg to the northeast, Milroy finally realized his predicament. He had also become aware that he was facing the entire Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia and at a council of war, Milroy and his subordinate officers planned to fight their way out. Union forces would advance from their defensive works west and north of Winchester and strike at the Confederates, which belonged to Johnson’s Division guarding the Valley Pike. The hope was that the attack would open an escape route toward safety to the north.

The next morning, Milroy’s Federals assaulted Johnson’s Confederates near Stephenson’s Depot approximately 5 miles north of Winchester. After a few failed unorganized assaults against the Confederates and the “Stonewall” Brigade advance that cut off the Valley Pike the fate of the Union garrison at Winchester was sealed. Some Federal troops singly or in small groups did escape and headed north or northeast toward friendly lines, but the majority of the troops capitulated. Approximately 4,000 Union soldiers now found themselves prisoners-of-war.

In his first major action in charge of a corps, Ewell had proven himself. His battle plan for Second Winchester was vintage Jackson. He examined the topography, sized up the enemy force, and used maneuver to cave in the flanks while moving to seal off the escape route. Second Winchester was another complete victory for the Confederacy.

Like Jackson’s action at Harper’s Ferry the previous autumn, the Valley was now clear of Union troops, allowing Ewell and the rest of Lee’s army to head northward without having an enemy force astride their line of communication and supply.

The Richmond Examiner reported about Second Winchester that Ewell’s command of the affair “equaled any movement made during the war.”

“The movement of Ewell was quick, skilled, and effective—in fact, Jacksonian” remembered Major Henry Kyd Douglas, a former staff officer for Jackson.

(courtesy of the NPS)

Another of Jackson’s former aides, Sandie Pendleton wrote to his mother; “Gen. Ewell is a grand officer.”

As Confederate soldiers went to sleep amidst the great spoils of Winchester—also reminiscent of a Jackson trait of overrunning and capturing large amounts of enemy supplies—their commander, Richard Ewell, seemed to be continuing where the late Jackson had left off.

In the near future, the Confederate army would move toward the Potomac River and into the North where one could believe that future action only portended future success for the successor of Jackson.

Sources Used:

“Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life” by Donald Pfanz

“The First and Second Maryland Infantry, C.S.A.” by Robert Driver Jr.

H.E. Howard Regimental Series-10th Virginia, 23rd Virginia, 37th Virginia

*Also, check out the Sesquicentennial Second Winchester Events just follow the links:

http://www.nps.gov/cebe/planyourvisit/civil-war-sesquicentennial.htm