The Tasmanian Devil of the Western Front

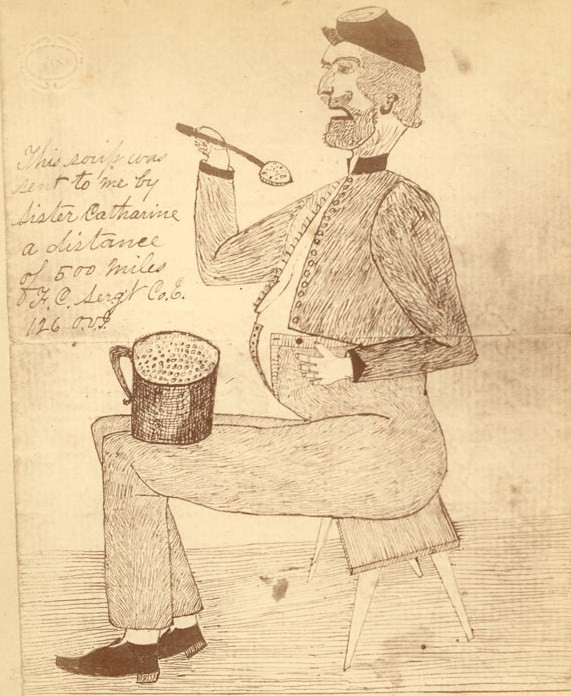

Military history is full of examples of individuals tending to exaggerate their influence on the outcome of an engagement. One needs to look no further than Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain or Philip H. Sheridan at Petersburg to see such evidence. But from the ranks emerges Sergeant Francis Cordrey of the 126th Ohio who puts all self-promotion to shame in a combat recollection that seems more at home in an animated cartoon. Sergeant Cordrey writes in his memoirs about his unit’s involvement in capturing the Confederate picket line on March 25, 1865:

for a few moments there was a tornado between Ft Welch and the rebel kingdom, sending smoke heavenward and thunder bolts forward, soon the storm subsided and when the cloud of smoke had lifted itself so that the onlookers could see beneath it, it was seen that the 126 Ohio was remodeling the works into a Union picket line, and had 200 rebel prisoners.

Cordrey told no factual lies despite his exaggerated spirit. After an unsuccessful Confederate assault on Fort Stedman on March 25 failed to loosen the ever-tightening Union stranglehold on the city of Petersburg, Ulysses S. Grant ordered the pickets all along the front to probe the enemy’s position in hopes to determine where Robert E. Lee had weakened his lines to muster enough strength for his desperate attack. The Union Sixth Corps occupied the portion of the extensive fortifications west of the Weldon Railroad with the Confederate earthworks protecting Boydton Plank Road as their objective.

After several unsuccessful piecemeal attacks, Major General Horatio G. Wright’s men eventually secured the enemy picket line by nightfall. Lieutenant Colonel Hazard Stevens described the advantages gained by this maneuver: “The advanced positions thus gained were of incalculable advantage. From them all the intervening ground to the enemy’s main line could be closely scanned, as well as his works themselves, and room was afforded to form an attacking column in front of our works and within striking distance of the enemy’s.”

Some historians argue Wright could have overrun the thinly held Confederate position on the afternoon of the 25th, and with the majority of its garrison hastening back from opposite Fort Stedman, that should have proven successful. Cordrey did not think much of his commanders, with Grant as an exception. Compared with “the number of fools [the army] made out of young boys that had been put in command through some unfair means,” he prized Grant as “that great general whose flesh had not been softened in the stew pot of useless pride and whose soul was not stiffened by the starch of vanity.”

Despite any blunderings, the Union army had regained the initiative and readied itself to bring the campaign to its climactic conclusion. After gains made at Lewis Farm on March 29, White Oak Road on March 31, and Five Forks on April 1, the Sixth Corps now had a golden opportunity to redeem criticism from Wright’s perceived overcaution. Grant ordered immediate assault all along the lines before dawn on April 2. Cordrey believed Wright’s reputation lay entirely in the hands of the men tasked with this bayonet charge:

Good officers are good things on a battle field, but historians should not overlook the fact, as they do, that the honor of victory growing out of battle takes it birth in the bravery and work of the private soldiers. It is a fact, that in all battles, nine-tenths of high official service ends after the command, Forward-march, after that the intelligence, strength and bravery of the common soldiers alone determine the result.

Thanks to their position gained the week before, numerical superiority, and personal bravery, the Sixth Corps captured the Confederate earthworks in short time. “On that morning,” he remembered, “as the sun overpowered the darkness of night and drove it back, so did the Union army overpower the dark rebellion and drove it back.” Cordrey showed little respect or admiration for his enemy; as they retreated, he observed they “seemed to drag [their] own bruised carcass back in search of a place to die.”

But he later realized the significance of the occasion: “At this stage of the battle,” he wrote in his memoirs, “the light of day begin to dawn, not only the light of the rising sun in the east, but the light of the rising sun of justice, freedom and liberty, that shall forever shine on every American citizen. Yes, we trust it was the dawning of a new day that shall know no more rebels in our land, no North, no East, no South and no West, and shall know but one flag and that flag the stars and stripes.”

Researchers would strain themselves trying to piece together the 126th Ohio’s military record from Cordrey’s meandering memoirs, but his recollections provide a brutally honest and amusing story not found in the Official Records—a reminder of the many unique faces of battle.

Francis Cordrey’s memoirs are accessible at the Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne, Indiana.