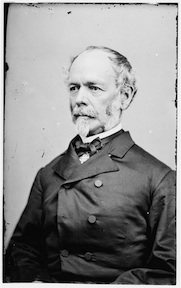

A Precipitate Retreat: General Joe Johnston and the Confederate Withdrawal from Northern Virginia March 6- 10, 1862

After their victory at the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, the Confederate armies of the Potomac and Shenandoah combined and settled into a defensive position from Leesburg in the west and the Potomac River near Occoquan in the east. Various outposts and encampments were set up around Centreville and Manassas Junction. The combined army was under the command of Gen. Joseph Johnston. Fellow hero of Manassas Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard was sent west. As the opportunity for an offensive against the Federal capital faded in early 1862, Johnston believed that the army should be withdrawn to a stronger defensive position. How and when Johnston pulled his army out of northern Virginia became a topic that was hotly debated. It also solidified Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ opinion of Joe Johnston.

After their victory at the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, the Confederate armies of the Potomac and Shenandoah combined and settled into a defensive position from Leesburg in the west and the Potomac River near Occoquan in the east. Various outposts and encampments were set up around Centreville and Manassas Junction. The combined army was under the command of Gen. Joseph Johnston. Fellow hero of Manassas Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard was sent west. As the opportunity for an offensive against the Federal capital faded in early 1862, Johnston believed that the army should be withdrawn to a stronger defensive position. How and when Johnston pulled his army out of northern Virginia became a topic that was hotly debated. It also solidified Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ opinion of Joe Johnston.

As Johnston’s army spread out over northern Virginia, his army and its soldiers were not yet professional warriors. The regimental and brigade camps were full of non-military inhabitants and supplies. At this point during the war, most officers who had personal man-servants or slaves brought them to camp with them. Even enlisted men were allowed to have large amounts of personal luggage and visitors from home. These volunteers of 1861 had not yet felt the harshness of war and a long campaign. No major fighting occurred in the region after July 1861, so a debonair spirit pervaded through many of the regiments. The men wrote how hard the winter was; it paled in comparison to their future marches and encampments. Johnston’s army became over burdened with personal baggage and a large following of civilians. These amateur soldiers expected to be able to have the many comforts of home while on campaign. The upcoming retrograde movement and the loss of these comforts shocked many.

Supplying an army required a lot of coordination and logistics for a new nation and bureaucracy. During the winter of 1861, the Confederates in and around Centreville were supplied well. Warehouses near Manassas Junction sat full of military and commissary stores. A million plus pounds of meat were stored near Chapman’s Mill at Thoroughfare Gap. Cattle were herded and penned in this same area. Using the Manassas Gap and the Orange-Alexandria railroads, the quartermasters were able to send supplies from the Shenandoah Valley and Richmond to Manassas Junction. To supply troops in and around Centreville, further north of Manassas Junction, the Confederates built the first-ever military railroad.

As the Confederates began to amass vast stores, Johnston began to inform the Confederate quartermasters and commissaries that their warehouses and meat houses were too close to the front. By March, over 3 million pounds of supplies were accumulated in the region, enough for two months. Johnston argued supplies should be moved closer to Culpeper, where they were safe and within distance of the army. If the Federals were to make a quick advance, they would not be able to remove everything.

Johnston also knew that his army was in no shape for a quick march—the government supplies and the soldier’s personal baggage would slow them down severely. Moving on poor country roads and having only one single-track railroad to pull back on took time. Furthermore, the Confederates had amassed large siege guns along the Potomac River in Prince William County in river batteries. These guns had successfully blockaded the Potomac from shipping, but getting those guns safely out of the batteries and moving south with the army was an extremely difficult task. With these things on his mind, Johnston went to Richmond in February to meet with Jefferson Davis and his Cabinet to discuss strategy.

Johnston met the newly elected President and his full cabinet on February 19th in Richmond. Davis and Johnston discussed strategy, and Johnston argued that unless reinforced for an offensive, his position was perilous around Manassas Junction. Davis and his cabinet officials agreed. The line of the Rappahannock or Rapidan Rivers provided a natural barrier and a location to consolidate the spread-out army.

Other than agreeing on the situation, though, Davis and Johnston agreed on nothing else. Both men left the meeting thinking something totally different than what the other thought. Johnston wrote after the war that he believed “the army was to fall back as soon as practicable.” As time showed, Davis believed Johnston was nowhere close to evacuating the Manassas Junction area.

As spring approached, Johnston began to make secret plans to withdraw. He did not trust the officials in Richmond to keep confidential information. On his return to Centreville, rumors about his upcoming withdrawal were rampant; someone from the meeting had leaked the information. Johnston, believing secrecy was important to hide his intention from the Federal forces, decided to communicate little with Richmond.

On the northern side of the Potomac, the Federal army, now under Gen. George McClellan, was much larger than Gen. Irvin McDowell’s army of 1861—nearing 100,000 men and bolstered by a large navy. Johnston could only muster 40,000 and had no navy to protect the waterways that led to his rear. McClellan was under ever-growing pressure to make an offensive, and Johnston knew it would happen soon. Johnston warned Gen. W.H.C. Whiting, in command of the Potomac batteries, that “we may indeed have to start before we are ready.”

On March 5, after receiving reports from his scouts that the Federals were especially active, Johnston ordered the evacuation of northern Virginia. What could not be moved was destroyed. The massive warehouses at Manassas Junction were opened to the men to grab what they could carry, and the rest was put to the torch. The newly built military railroad was dismantled; even the famous stone bridge on the Bull Run battlefield was blown up. What guns could not be moved from the Potomac batteries were spiked and pushed into the river. The meat warehouse at Chapman’s Mill was destroyed after offering local farmers a chance to supply themselves with some free meat. Many regiments lost all their camp equipage and supplies. “Manassas was burnt up and it was the greatest destructing I ever saw in my life,” wrote Private Sidney Richardson of Georgia.

After four days, the evacuation was complete, and the army began to reassemble south of the Rappahannock River. To Johnston, the withdrawal was the best that could be accomplished. The citizen soldiers were not prepared for quick movement, and he was glad that many had to leave their personal baggage behind. On March 10, Federal infantry entered Centreville and saw everywhere signs of a hurried retreat.

On the same day the Federals entered Centreville, Davis sent Johnston a message about possibly sending him reinforcements and using these men to move beyond the Virginia border. In response, Johnston finally informed his superior of the retrograde movement. Davis was astonished, he wrote Johnston. “It is true I have had many and alarming reports of great destruction of ammunition, camp equipage, and provisions, indicating a precipitate retreat,” the Confederate president wrote; “but, having heard of no cause for such a sudden movement, I was at a loss to believe it.” According to Davis, he had no idea or information that Johnston was going to withdraw in early March. Davis was actually planning on sending Johnston more men for a possible advance.

The Confederate withdrawal in March 1862 solidified Davis’ poor opinion of Johnston, who was disinclined to communicate with the President about his intentions. Johnston did not respect Davis and his advisors. He believed military matters should be left to the military men (Davis, as a West Point graduate and a former U.S. secretary of war, believed he was one).

A lot of what these men said about the March withdrawal was in dueling postwar narratives, but there are a few indisputable facts. First, the position of Johnston’s army in March of 1862 was dangerous at best. He could have easily been flanked and had little to be gained by holding northern Virginia. Second, the army accumulated too many forward supply bases and warehouses. The Commissary did a noble job accumulating supplies, but they were too close to the front lines. Thirdly, Johnston’s retreat was too hasty. He should have made detailed plans to remove the valuable stores and ammunition from the front. The men later in the war talked about the “great barbeque” as they smelled the burning meat from Thoroughfare Gap. The lost supplies and armaments were badly needed in the supply-strapped Confederacy. Finally, Johnston’s secrecy about his movement to his superiors was unacceptable. It is understandable his lack of faith in the confidential communications with Richmond, but it is obvious Davis had no idea his largest eastern army pulled back 30 miles closer to Richmond.

Due in large part to this “precipitate retreat,” Davis limited Johnston’s authority by bringing in a military advisor who he respected and trusted. On March 13th Gen. Robert E. Lee became that advisor.