The Myth of the “Cracker Line”: Part One

We are excited to welcome guest author Frank Varney. Frank is the author of General Grant and the Rewriting of History: How the Destruction of General William S. Rosecrans Influenced Our Understanding of the Civil War. Part one in a series.

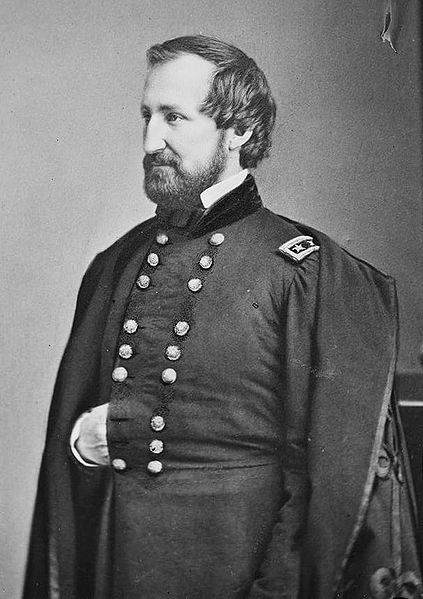

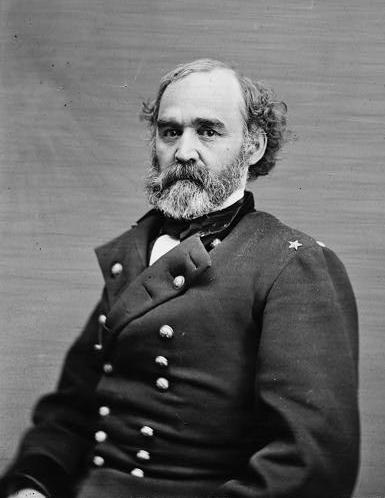

If you look in pretty much any history of the Civil War that discusses the siege of Chattanooga that followed the Union defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga, you will find some assertion that General William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, went into a state of depression which essentially destroyed his capacity for command. From an intelligent, aggressive commander he supposedly turned into a dazed wreck – his confidence shattered, his spirit broken, unable to take even the most basic steps to keep his army supplied and in fighting trim. The accepted history goes on to say that it required the energy of Ulysses S. Grant, who was appointed to overall command of Union forces in the region, to save Rosecrans’ army. Grant relieved Rosecrans, replaced him with George H. Thomas, and promptly set about devising a remarkably clear plan for getting the supplies flowing. The energy and resourcefulness of Grant resulted in the opening of the “Cracker Line” in an incredibly short time, which saved the Army of the Cumberland. This is often, in fact, considered one of his more noteworthy accomplishments.

That is not, however, the case. A closer examination of the primary sources reveals that in fact there is much more to the story than that. The question that must therefore be asked is a simple one – was Army of the Cumberland starving and did Grant rescue it from oblivion? Let’s see what some of the leading historians have to say about it and where they got their information.

• According to J. F. C. Fuller, “within five days of Grant’s arrival in Chattanooga, the road to Bridgeport was opened, and within a week the troops were receiving full rations, were being reclothed and resupplied with ammunition, ‘and a cheerfulness prevailed not before enjoyed in many weeks. Neither officers nor men looked upon themselves any longer as doomed.’” The source Fuller cites for this—and the source for the quote he uses to strengthen his statement—is Grant’s Memoirs. According to this version, with the improved supply route in place, the Army of the Cumberland swiftly regained its strength until it was ready to resume offensive operations.

• Ernest and Trevor Dupuy say that Grant “arrived at Chattanooga on [October 23rd]. Then things began to happen. In a few days food was abundant, worn-out clothing and equipment had been replaced, and the meager store of ammunition had been replenished. The Army of the Cumberland was ready to fight again.” The Dupuys provide no source for this statement, but it sounds remarkably similar to what Fuller had to say—and Fuller’s source was Grant.

• Popular historian Robert Leckie says, “The situation could hardly have been worse, and for Grant, whose spirit thrived on adversity, that was tantamount to never being better. Almost at once he determined to open a supply line. Thus was opened the famous ‘cracker line’ over which troops and supplies came into Chattanooga.”

• Geoffrey Perret does not give Grant all the credit, but does accept the idea that the Army of the Cumberland was in danger of starving—although he gives no source for that statement.

• William B. Feis claims that “Rosecrans faced a severe shortage of supplies and nerve” and said that Grant opened “the famous ‘Cracker Line,’ which helped alleviate some of the suffering.” Feis cites Grant as his source.

• James Marshall-Cornwall notes that Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23, that the operation to seize Lookout Valley was completed on October 28, and notes that “[t]he army’s supply line was now secure. It was known by the troops as the ‘cracker line.’ Within a week of Grant’s arrival, his army was restored to full rations. The establishment of the ‘cracker line’ was quite an engineering feat.” He gives no source for that specific statement, but the only source cited anywhere in the chapter is Grant’s Memoirs.

• Jean Edward Smith says, “For Grant, the initial task was to reestablish a viable supply route . . . what he called ‘a cracker line,’” although Smith acknowledges that the plan had been designed before Grant’s arrival—by George H. Thomas and “Baldy” Smith, with Rosecrans coming in for no credit. According to his footnotes, his source is Grant.

• Henry Coppee, writing soon after the war, called the operation—which he attributed solely to the genius of Grant—“in judgment, skill, celerity, and results, second to none in military history. It was the very poetry of the art.” Coppee did not give any specific source for his statements, but in his preface he commented that while composing his manuscript he had depended “upon the masterly—I may say, model—report of General Grant. I must express my hearty thanks to General Grant for his kindness in sanctioning my attempt to portray his military career.” He also expressed his appreciation of John Rawlins, Grant’s former chief of staff, “for his invaluable assistance in furnishing materials without which the work could not have been written.” Coppee said that without the efforts of Grant and Rawlins, “most of this material could not otherwise have been obtained.” That certainly sounds as though Grant had quite a bit to do with supplying Coppee with his source material. Thus, like so many others, Coppee depended—for a book about the generalship of Grant — on Grant for most of his information. Up to a point, this version of the story is correct—but only up to a point.

There is ample evidence that the Army of the Cumberland was suffering from supply problems—caused mainly by the activity of Rebel cavalry, which continually cut the few available roads into Chattanooga—and by the terrible condition of the roads themselves, exacerbated by miserable weather. Long before the campaign had even begun (in fact, before he had even begun the Stones River campaign, which precede this one) Rosecrans had predicted trouble if his mounted arm was not strengthened, and his predictions came true; nor did his entreaties for more cavalry end with Chickamauga. He sent messages to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck on October 1 and 2 and to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton six days later on that subject. He had also been assured by the War Department that he would have the support of General Ambrose Burnside, whose command, stationed in Knoxville, might have been able to help hold the lines open: that support never arrived.

Evidence also exists, however, that conditions were not as bad as they have often been represented. In the archives at Stones River and Chickamauga- Chattanooga there are copies of hundreds of letters and dozens of journals written by men present in Chattanooga during the siege. Remarkably few of these documents record any serious shortage of food, although many complain of the monotony of the diet. A commonly-quoted witness reported seeing men following supply wagons and picking up dried corn that had spilled from them. The implication is that hungry men were scavenging food to fill their empty bellies, but it is at least as likely that they were trying to find fodder for their starving animals. Although it appears that horses and mules were suffering terribly due to a lack of forage, the men—while in some cases on severely reduced rations—seem to have been in no imminent danger of starvation. In fact, some of them said that they were eating fairly well. Consider the following journal entry, for example: “October 5. . . We got some potatoes, apples, etc. . . the country in which we were to forage contained plenty and we did not want for meat etc.”

However, the reports of Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, designed to injure Rosecrans in order to help Secretary of War Stanton establish a case for his removal, deliberately emphasized the shortages. Rosecrans, in attempting to convince Halleck that he needed assistance, may also have overstated the difficulties he faced. And Grant, anxious to make Rosecrans look as bad as possible, certainly misrepresented the situation after the fact. Grant said in his Memoirs that the army was in a sorry state when he arrived in Chattanooga: starving, shoeless, with no fuel for cooking or heating, and in a terrible state of morale. Rosecrans took great offense to Grant’s statements about the condition of the Army of the Cumberland. He stated emphatically that “[w]hen I left it . . . the Army of the Cumberland was in no such condition.” Rosecrans went on to say that there was fuel in abundance, and that “[t]eams were hauling and delivering rations.” He took particular note of the fact that Grant’s famous message to Thomas directing that Chattanooga be held at all costs—sent when Grant assumed overall command and relieved Rosecrans—was the source of great annoyance to both Thomas and Rosecrans, neither of whom had any intention of doing otherwise.

In his Memoirs, Grant gave Thomas’s oft-quoted reply—“We shall hold the town until we starve”—but did not give the rest of the sentence: “our wagons are hauling rations from Bridgeport.” Grant also withheld the remaining details of Thomas’s reply, which went on to say “204,462 rations in storehouses, 90,000 to arrive tomorrow.” That certainly seems to indicate both that the Army of the Cumberland was not on the brink of starvation—not with more than 200,000 rations in storehouses in Chattanooga (enough for approximately five days), with enough for two more on the way—and also that the supply line was open, since more supplies were due to arrive the next day. Historians have repeatedly accepted Grant’s version of his message and Thomas’s reply, to the point that it is probably one of the most famous quotations of the war; unfortunately, the rest of Thomas’s statement is almost never discussed.

A journal kept by one soldier had the following notations. On October 10, he reported the men were in possession of “chickens and vegetables . . . fresh pork and mutton also.” The next day he noted “forage is abundant. . . . The boys have attacked a lot of hogs and skirmishing is brisk, so I must put on the pot as I smell fresh pork.” On October 17, he wrote of confiscating “nine barrels of sorghum molasses . . . also 60 bushels of sweet potatoes.” On October 18, he reported, “We are now living on sweet potatoes.” He noted a shortage of hardtack and meat, but there is little or no evidence in his journal of true hardship. Nor does the purported shortage seem to have affected his feelings for his commander, for in a later entry he noted, “It is rumored that Rosecrans is to be superseded by U. S. Grant. We hope not for although Grant may be a splendid man, yet Rosecrans is our favorite general. No man could have done better than he has. We all have confidence in him and he is a man the rebels fear. If the change is made we hope it is for the best and for the good of the country and not to gratify petty spite.” Another officer flatly stated, “At no time did the men suffer, and at no time were the troops of the Cumberland either discouraged or demoralized.”

Division commander Philip H. Sheridan said that he was able to obtain “large quantities of corn for my animals and food for the officers and men. [I]n this way I carried men and animals through our beleaguerment in pretty fair condition.” It certainly appears that, although shortages did exist, some units suffered less than others. No doubt there was hunger in the Army of the Cumberland, but it was far from universal. What hunger there was cannot be solely attributed to any error of Rosecrans; even if Grant had not relieved Rosecrans, it likely would have been ended in short order. It is certainly possible that conditions deteriorated quickly between Rosecrans’s departure and the operation that fully opened the supply line, but it would have been fully opened in any case, and very soon.

Nor did Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, sent to Chattanooga to discern the truth about conditions there, share the belief that the army was in dire straits. According to a newspaper report, he disagreed with “the opinions expressed by arrivals from the army, that it was disheartened, demoralized, &c. On the contrary, he declares that it is in excellent condition and fully equal for any emergency.” That could be dismissed as a statement for public consumption, if not for the fact that it pretty much agreed with what Meigs said in his dispatches to Washington. On September 27, he informed Stanton that he had found the men to be “vigorous, hearty, cheerful, and confident.” Of the defenses of the city he noted that “the position is very strong already, and rapidly approaching a perfect security against assault. Nothing but a regular siege could, I think, reduce it. When the river rises the bridges will go, but the river will become navigable. One steam-boat and a few flats are ready for service. Another steam-boat is nearing completion. For another the machinery is at Bridgeport.” This certainly sounds as though Rosecrans and his staff were making energetic efforts to improve things. “When the troops understood to be on their way here arrive, General Rosecrans expects to recover command of the river to Bridgeport. Supplies can then be accumulated by water.” This seems to indicate that when Sherman arrived, Rosecrans would be able to finalize his efforts. Of course, he would not get the chance to do so; Grant would arrive just ahead of those troops, admirably complete what remained to be done, and get the credit for having done it all. “[A]nimals still in very fair condition, so far as I have seen them. Plenty of them here and at Nashville.” That does not sound as though the situation at that time—only a few weeks before Rosecrans’s removal—was critical or even nearing that point.

It is worth noting that one of the criticisms that Fuller made of Rosecrans was that he “made no effort to run boats down the river. There were two at Chattanooga, and these could have brought 200 tons of supplies daily.” According to Meigs, however, the reason Rosecrans did not use them was because the river was not yet deep enough to make it possible. By the time it was, Rosecrans was gone and Grant was in charge.

(Please email Emerging Civil War if you desire footnotes for this article.)

Very well done article.

HMS, NC

Varney’s essay is a good corrective to the myth that has grown up in the historical record regarding the “starvation” under Rosecrans during the siege of Chattanooga. When I was a boy I remember reading Bruce Catton’s portrayal of the dire conditions in the city–until, of course, his hero Grant arrived. We now know differently: but the “spin” which Grant and his supporters put on the situation at the time continues to affect–and infect–the secondary accounts to this day.

I am all thumbs when it comes to using the”O.R.s”, so I was wondering what the official correspondence was 3 weeks before and 3 weeks after Grant’s arrival.any leads in this direction would be grateful as it would open up this excellent article to more views either way

Thank you, Frank Varney, for this blog post and Emerging Civil War for opening the forum for discussion. You can read more about the book, including an excerpt and author interview at publisher Savas Beatie’s website here: http://tinyurl.com/c889m3o.

Personally signed copies are available upon request. Please e-mail sales@savasbeatie.com for more information.

Excellent post. The Grant narrative in regards to Rosecrans is not reliable.

By the Spring of 1862 the Union was looking for a hero to give them courage and enthusiasm to continue and hopefully “win” the war they were struggling with since 1861. U.S. Grant became that “lighting rod” that gave new life to a final series of blows that would finally destroy the Southern Confederacy. Grant was laced with a deadly cancer while writing his memoirs, so Id give him some comfort for creating or at least “using” a Cracker Line to same the Union troops in Tennessee and Bridgeport, Alabama. So Thomas or Rosecrans created it, but Grant used it to defeat the South and send Sherman toward Atlanta. I would not called Grant a “Teflon Man”, or “Marble Man”. But was a flawed hero who was surely “The Man.”

According to my research Professor Varney has a history of “sloppy” historical work. This is a quote from another blog, where evidence the professor took Memoirs written decades after the war as the wartime after battle report.

“So to recap, Varney wrote “Maury said in his after-action report” and then quotes something that is not in Maury’s after-action report and footnotes to something that is neither Maury’s after-action report nor the source of the quote. This has the facade of scholarship — an official looking footnote — that fools some people into thinking Varney has ‘built solid cases’ and ‘examined primary sources’, but it is actually sloppy and misleading work that I find disturbing from a history professor.”

I wouldnt take the professor too seriously.

This is more Southern rewrite of history. Pretty soon we will find out that Grant surrendered to Lee. That’s what you do if you don’t like what really happened.

Bingo … this gent also wrote an entire book on Grant and Rosecrans … a meandering revisionist tale that essentially says there was a vast conspiracy against Rosecrans … and that Rosecran’s record of 1 win at Stones River (a questionable one at that) and 1 loss at Chickamauga would have been much better had everyone not been “out to get him.”