The Myth of the “Cracker Line”: Part Two

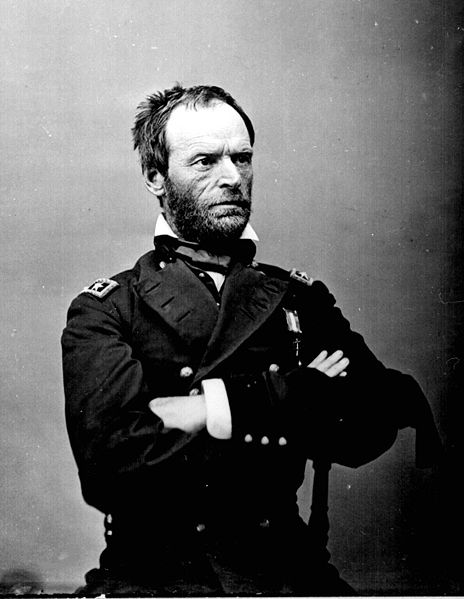

We are excited to welcome back guest author Frank Varney. Frank is the author of General Grant and the Rewriting of History: How the Destruction of General William S. Rosecrans Influenced Our Understanding of the Civil War. Part two in a series (click here for part one).

Of the railroad connection from Nashville, Meigs commented, “The iron is reported on the ground; all but 4 miles graded.” His final judgment was that “[t]hings look much better here than I expected to find them when I left Nashville; still success will demand efforts from the army and from the country. Of the rugged nature of this region, I had no conception when I left Washington. I never traveled on such roads before.” In this last, Meigs echoed Dana, Rosecrans, Grant, and myriad others. On October 1, Meigs told Stanton, “This army is most ready, and laborious as well as courageous. It builds its own bridges, makes pontoons, and lives within itself. It is in many respects most admirable.” Again, this is not a picture of a beaten and demoralized army, starving and lacking faith in its general.

Two days later Meigs reported to Stanton that “[t]he fortifications of this place are steadily increasing in strength. The men work cheerfully, and with skill and ingenuity.” Of sustenance he reported that “[arrangements have been made] to ship from Louisville by railroad the grain needed to supply the animals belonging to the artillery, to the officers, and to the trains with full daily rations. The cavalry horses will be able to subsist for some time to come upon the country. At this season of the year the corn is in the field, and ripe. Though not dry enough for storing in granary, it furnishes food for man and beast.” This hardly sounds like an army on the verge of starvation.

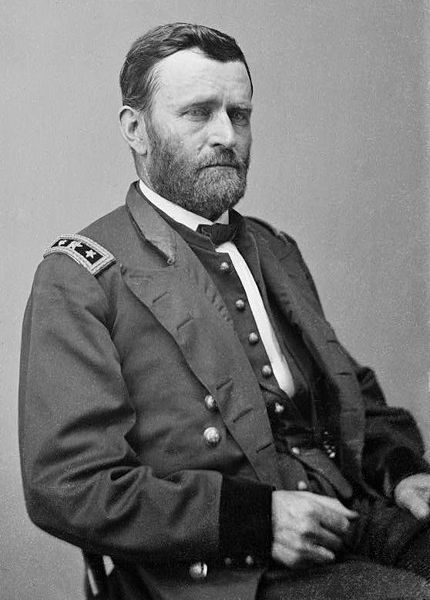

In his Memoirs, Grant noted that Rosecrans’s chief of engineers (General William F. “Baldy” Smith) had put a sawmill into operation, had one bridge completed, was well on his way to constructing another, was assembling materials for a third, and had an ingeniously improvised steamer in operation on the river—but he stated it in such a way as to make it appear that the officer had done it entirely on his own. There is no hint of credit due Rosecrans for the accomplishments, even though they had of course been achieved while he commanded the army. It is probably safe to assume that he at the very least approved the operations of his chief engineer, and very likely had ordered their implementation.

Grant also commented that Rosecrans had “excellent” plans in place to establish an efficient supply line that would have fed his army with no difficulty, and “my only wonder was that he had not carried them out.” William McFeely says that Rosecrans “had many intelligent suggestions about how the army should proceed, and Grant could only wonder why Rosecrans had not himself put them into effect.”If that sounds familiar, it is because McFeely’s source, according to his own citation, is Grant. In fact, such implementation had already begun. Rosecrans had issued orders to take all necessary steps to improve the line of communications, as may be plainly seen in the OR by anyone willing to take the time to make a close study of them rather than merely relying upon the writings of Grant. However, there is another source that supports this position: the testimony of the soldiers in the ranks.

On October 10, Sergeant-Major Lyman Widney of the 34th Illinois recorded in his journal that conditions were expected to improve very soon, since the supply line had been opened that same day and troops and batteries had been deployed to guard it. More interesting, however, is the entry for October 11, which states, “the cracker line is in working order.” In fact, the first journal reference using the name “Cracker Line” is as early as October 5, and Widney used the term again on the 6th. At that point the line was not yet completely open, but, given the fact that it was being referred to by name, it clearly was a project already in the works. According to Widney, supplies were flowing freely on the 11th.

This is a very significant document. Widney referred to the Cracker Line on October 5 as something that had been undertaken; again on October 6 as an ongoing project; and that it was open on October 10, more than a week before Rosecrans was relieved and nearly three weeks before Grant supposedly established the supply line that fed the Army of the Cumberland. Other letters and journals also make reference to the Cracker Line, and, although not all are dated, their context indicates that the line was opened prior to the relief of Rosecrans, not after.

There is also the official record to consider. On October 10, Rosecrans received a message informing him that the depot in Nashville was “pushing forward cattle by land and railroad; shipped 200 to-day by railroad; am sending other stores also.” On the 12th, Meigs informed Stanton that “I have given such orders and taken such steps during the seventeen days I have spent here as will, I think, much aid this army, and I do not think my presence here longer will be of much service.” That message, sent less than a week before Rosecrans was relieved, sounds remarkably like a man who views his task as completed—unlikely if the army were approaching a crisis. Also on that day, Rosecrans informed the officer in charge of shipping material forward from the railhead that the desired priority of shipment was for “First, troops; second, rations and forage; third, beef and forage, fourth, army transportation.” If his men were starving, it seems unlikely he would have given the first priority to the transportation of more mouths to feed.

On October 14, Rosecrans received a telegram from the War Department informing him that three million rations were en route, if he could find a way to transport them from the railhead to Chattanooga; he replied that they should be sent as planned. If the supply system did actually collapse and hunger became a serious problem, it does not appear that it could have happened before, at the earliest, October 14 or so—not if the efficient, thorough, and well-regarded Meigs was telling us the truth. That means that any serious deficiency—assuming one ever existed—lasted only a handful of days, and would have been addressed very quickly whether or not Rosecrans was relieved.

It is more probable that the purported “starvation” of the Army of the Cumberland is a myth. In a letter written October 18, Alfred L. Hough told his wife that, due to a recent cavalry raid, “we are now short of rations.” This implies that there was no shortage before. He also said that if he had been suddenly propelled from the comforts of home to his present situation he would have found it very difficult, “but we have become used to it,” which again does not imply severe hardship. On October 20, Hough wrote that the army had rations for another 12 days, and “if the roads do not get better by that time” things could become dire. That indicates that there were sufficient rations on hand at the time of Rosecrans’s removal to last into early or mid-November, even if there were no new supplies brought forward; however, Rosecrans had already opened the supply line, and was nearly ready to secure it, well before November.

Grant claimed that from his arrival in Chattanooga it took him a week to open the supply line; in fact, the line was open nearly two weeks before he arrived. He did implement a plan to strengthen it, but that plan had been designed by Rosecrans, who had begun preparations for it. Even Philip Sheridan, second only to Sherman among the “Grant men,” said that at the time the change of commanders took place “Rosecrans was busy with preparations for a movement to open the direct road to Bridgeport.” According to Sheridan, the arrival of Hooker and his men had given Rosecrans the resources he needed, and “[w]ith this force Rosecrans had already strengthened certain important points on the railroad . . . and given orders to Hooker to hold [his forces] in readiness to advance toward Chattanooga.” Sheridan also said that once Grant arrived he “began at once to carry out the plans that had been formed for opening the . . . road to Bridgeport.”

Rosecrans had, at the time he was relieved of his command, opened a supply line—dubbed the “Cracker Line” by the troops—and had taken steps to strengthen and improve that line by seizing Brown’s Ferry and Lookout Valley. His plans were already in train when his command was abruptly terminated. That is why Grant was able to launch such a large and complex operation three days after his arrival. To this day, Grant has gotten the credit for it.

Shortly after the war, there was a great deal of controversy over who should

receive the acclaim for the plan. Brooks Simpson, in an effort to cut through the logjam of debate, has said, “Rosecrans, Thomas, and [General William F.] Smith each claimed the honor for themselves. However, it was left to someone else to make sure that it was implemented.” According to Simpson, Grant should get the credit for putting the plan into place; who designed it is moot. That seems logical, to a point. Of course, Rosecrans was about to implement his plan when Grant relieved him of command; Thomas was the man in charge of the operation, even if Grant was in overall command; and Smith, who was chief engineer of the Army of the Cumberland, did not have the authority to implement anything without the permission of his commanding officer. So, although Professor Simpson clearly thinks Grant should get the credit for putting into operation a plan someone else designed, approved, and implemented, that credit goes to Grant only by default.

In fact, no less an authority than George H. Thomas publicly placed the distinction where it belonged. When he ordered Hooker forward, Thomas told him to execute the movement “planned by General Rosecrans.” In his report of the operations to secure Brown’s Ferry and open Lookout Valley—operations for which Grant claimed credit, and which are generally taken as the final act that secured the “Cracker Line”—Thomas opened by saying, “In pursuance of the plan of General Rosecrans, the execution of which had been deferred until Hooker’s transportation [had arrived] . . .” General Joseph Hooker said that the plan of the operation was “communicated to me by Rosecrans long before I ever saw Chattanooga.” Historian Geoffrey Perret, who seldom gives Rosecrans much credit, perceptively states that the plan “would have been implemented even if Rosecrans had not been fired.” A court of inquiry convened in 1900 by then-Secretary of War Elihu Root took Hooker’s statement into account when it found that “there is abundant evidence in the Official Records to show that the plan was devised and prepared by General Rosecrans.” Of Grant’s role in the operation, Rosecrans said that it “would have taken place all the same had he never lived.”

Bruce Catton, one of the remarkably few historians not to give Grant all the credit for the “rescue” of Federal forces in Chattanooga—although he gave no details as to why he felt that way—said that it was entirely possible the Federal troops would have broken the siege “even if Grant had never gone near Chattanooga.” Grant’s attempt to claim credit for this operation, as well as his attempt to claim credit for a victory at Chattanooga a few months later, Rosecrans later characterized as “insatiable and conscienceless egotism.” Here Rosecrans may have gone too far. Grant did acknowledge, in fact, in his report to Halleck, that the plan had been designed not by himself but by Smith and Thomas—but he gave no credit to Rosecrans.

Once we examine the primary source documents – other than those of Grant – it becomes apparent that what we thought we knew about the Cracker Line needs to be rethought. And if we accept that what we thought we know was wrong (something many people are astonishingly unwilling to even consider) than that should lead us to ask another question: what else that we thought we knew about Ulysses S. Grant, and his campaigns, needs to be reexamined?

(If you desire the footnotes for this post, please email Emerging Civil War.)

This is an excellent article. A re-examination of many of General Grant’s claims from his Memoirs is long overdue.

Not sure how this relates to the debate, but here are some relevant excerpts from the diary of Sergt. William T. Clark, 79th Pennsylvania, during this time period:

(http://www.lancasteratwar.com/2011/09/better-know-soldier-william-t-clark.html)

10/6: “River is falling. Steamboat is carrying Corn & fresh beef to our side of river.”

10/7: “We are living upon 2/3 rations”

10/26: “Half rations of hard bread & fresh beef, other things quarter.”

11/4: “Drew two days half rations of flour. Supplies are now brought for us from Bridgeport on Steamboats, landed ten miles down the river & then hauled to this place in wagons.”

11/7: “We have ¾ rations issued for the next 3 days. This is an increase of ¼ in the past month & a half.”

There is a very good 1962 book about Rosecrans,” Edge of Glory”, I forget the authors name.

A lot of things are finally coming out about how Grant and Stanton fought and tried to destroy Rosecrans. Also, in western VA in 61 Rosecrans won a battle with a flank attack while Mcllellan

froze on the front. He then took all the credit for it, which is what got him the Army of the Potomac and General in Chief where he spent most of his time basically refusing to prosecute the war. Rosecrans was far from perfect but he might have been our best Union General. He was certainly our most abused

P.S. Thanks Mr. Varney!

You’re welcome, Joe. And the author of Edge of Glory was William Lamers.

I’m enjoying reading Wiley Swords book on this campaign and after a brief scan saw no reference to it? I got no impression that Grant was taking much credit for any of this. But mostly he was relieved.

I think the author may have a point. However, the impression Abraham Lincoln had was that Rosecrans behaved as if “he were a duck hit over the head.” In the following year, Grant was defeated as badly as Rosecrans at Chickamauga, he moved and attacked again, ultimately bringing Bobby Lee to bay. It strikes me that if Rosecrans was a commander the equal of Grant, he would have been preparing for a counter stroke if his supplies were as adequate as portrayed herein. That he did not, speaks for

Much about why Lincoln liked Grant and did not like Rosecrans.