Following Orders: from “your Obd’t Servant” to SMEAC and METT-T

The Battle of Gettysburg has produced no end of enduring controversies, discussions, and disputes. Recently, on one of the Facebook sites devoted to exploring that battle, one such discussion surfaced yet again.

This time the question was about J.E.B. Stuart, and his famous ride. Was Stuart late? Did he disobey Robert E. Lee’s orders and leave the Army of Northern Virginia blind as Lee’s men ran into the leading elements of George G. Meade’s Federals outside of the Pennsylvania college town? Or were Lee’s orders at fault – too vague, too open-ended, perhaps.

Plenty of historians have taken their stab at answering that question. I myself wrote a piece for Gettysburg Magazine some years ago, but among the best works addressing this affair is co-written by Emerging Civil War’s own Eric Wittenberg – Plenty of Blame to go Around, published Savas-Beatie. At 456 pages, Eric and his fellow author J.D. Petruzzi have plenty to say about Stuart’s mission. Their choice of title aptly sums up their conclusions.

However, Stuart is far from the only general to misconstrue or disobey his instructions, Lee is not the only commander to produce an overly-vague order, nor is Gettysburg the only battle to hang on the balance of such a haphazard happenstance. The Civil War is replete with confusion and after-the-fact controversy. McClellan’s orders to Burnside at Antietam, Burnside’s orders to Franklin at Fredericksburg, Johnston’s orders to Pemberton during the Vicksburg Campaign, Bragg’s orders in just about any battle you could name – I could go on.

The post-war professional army was of course dominated by Civil War generals at all levels, most of them graduates of the Military Academy at West Point, and most of whom realized that however fond they were of that institution, it did more to prepare them to become lieutenants and captains than it did for them to command large formations in time of war.

Among those who reflected on the hard-won lessons of the War of the Rebellion was William T. Sherman, who served as General-in-Chief of the United States Army from 1869 until his retirement in 1884. Through the 1870s, a number of officers pushed for an advanced training school to be established to help infantry and cavalry officers hone their skills. Such schools already existed for the artillery and engineers, the two most technical branches of the army. Emory Upton and William B. Hazen, having observed European methods, urged just such a course for the remaining branches. John Pope, who had his own misfortunes with command on the plains of Manassas, “urged the concentration of two or three regiments at Leavenworth ‘for military exercises and instruction.'”[1]

Sherman was receptive. In 1881, he ordered the establishment of the “School of Application” at Leavenworth, and directed that each regiment send one lieutenant there for a two-year course of instruction.

The idea was not well received, partly because it was poorly executed. Regiments sent woefully under-qualified officers, forcing the school’s instructors – often barely qualified themselves – to create remedial courses in reading, writing and math. As a result the school quickly became known as the army’s “kindergarten.” The idea probably would have lapsed, written off as a failure, if not for the arrival of two men.

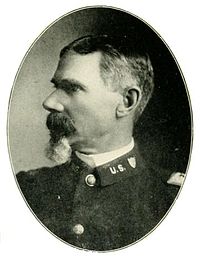

The first of these was Colonel Alexander McDowell McCook. McCook commanded a

division at Shiloh, and a corps at each of the battles of Perryville, Stones River, and Chickamauga. At Perryville his command was attacked by a much smaller Rebel army and nearly broke while the rest of the Federal army looked on, hamstrung by command failures from above. At Stones River McCook’s wing was a attacked again, surprised and all but wrecked. At Chickamauga, his corps was routed and driven from the battlefield.

Despite these reverses, McCook loved the army, and was well liked by his fellow officers. He served as Sherman’s aide in the late 1870s. In 1886, McCook was assigned as the School of Application’s new commandant, and immediately began a course of reform. Instructors were vetted for qualifications and ability. Students now had to pass an admissions exam to get in. Classroom time was expanded, and lessons made much more rigorous. These reforms had the desired effect, and the school’s reputation, as well as the quality of its graduates, markedly improved.

The second man was Captain Arthur L. Wagner. Wagner was younger, not a veteran of the great rebellion, but he was an exceptionally talented deep thinker concerning military affairs. McCook made Wagner an instructor, where he remained for most of the next decade. Wagner wrote extensively, earning a reputation as one of the army’s intellectuals, with many of his texts becoming required course material at the school. He would move on to both field commands and more advanced training billets, including helping to establish the Army War College in 1901. Meanwhile, Leavenworth continued to provide an advanced education. In 1907 its name was changed to the School of the Line, and today it is known as the Command and General Staff College. The CGSC still plays a vital role in readying officers of all branches for higher command.

What has this to do with orders? Simple. The School of Application placed an early premium on clearly written instructions, logically structured to define a commander’s intent in ways that could not be misunderstood. Over time, the school’s emphasis shifted from minor tactics to command at the brigade and (ultimately) divisional level. One key element of that preparation was the emphasis on the “Leavenworth Order,” which institutionalized a specific, logic-driven orders-writing style throughout the army. By the time of the U.S. Army’s massive expansion during World War One, Leavenworth-trained men were highly prized among commanders of the new divisions and corps springing into being.

The modern military still uses the concept of the “Leavenworth Order,” though of course it has evolved dramatically. Over time it became known as the Five Paragraph Operations order, further defined by the acronym SMEAC: Situation (enemy and friendly), Mission (what does the general want us to do?), Execution (how do we do it?), Support (attachments, air, artillery, etc.), and Command (everything from who is in charge to code-words, radio frequencies, and rally-points.) Of course, the five paragraph order has grown considerably over the years; today even a simple example order includes many additional bullet points and sub-paragraphs.

In recent decades, a new acronym has come to dominate the orders distillation process: METT, also known as METT-T. Mission, Enemy, Terrain, Troops, and (sometimes) Time. Be it SMEAC or METT-T, in each case, by following that formula, officers are forced to consider each of the essential aspects of their orders and how they might accomplish them. Size and complexity vary, of course, depending on the scope of the task, but at heart the concept remains the same.

It can be interesting to apply these concepts to Civil War orders that survive in the Official Records or elsewhere. In many cases the reader can quickly see where those earlier orders fail on essential points, or how confusion can be amplified by a poorly worded command. Did Lee fail to consider all the ramifications of that fateful order to Stuart? Did Stuart disobey his instructions? Had they been part of a Leavenworth exercise, probably they both would have received failing marks.

One final note. An important element of the School of Application’s training process were field exercises, among which were battlefield staff rides. Our beloved National Military Parks got their start in part for exactly this purpose. The enabling legislation stated that we need the parks “. . . for the purpose of preserving and suitably marking for historical and professional military study the fields of some of the most remarkable maneuvers and most brilliant fighting in the war of the rebellion.”

Certainly that wording echoes in my thoughts when I walk a battlefield.

[1] Timothy K. Nenninger, The Leavenworth Schools and the Old Army, Education, Professionalism, and the Officer Corps of the United States Army, 1881-1918 (Westport CT, Greenwood Press, 1978), p. 20.

Very well said. Looking back from the perspective of the 21st Century and through the military history of the 20th, it is easy to forget that the officers in the Civil War commanded units and operations on a scale never before seen in American military history.

One of the Army’s strengths is the ability to synthesize lessons for future use. I was not aware of McCook’s role at Leavenworth, although it is fitting for a former USMA tactics instructor (as he was).

I am fascinated by how much the war changed the military, be it tactics or in the art of command. McCook has this reputation as a big buffoon, and we dismiss him as a “political” general, but I think it is fair to remember that he had a long distinguished career in the post-war army. Same with John Pope.

Fascinating, Dave.

One might well argue that McCook made his greatest contribution to the American military establishment once he was no longer in a position to get XX Corps men needlessly killed…