The Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg: Part One

On the morning of July 1st, 1863, Union and Confederate soldiers made their way towards the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. Three full days of viscous fighting were touched off three miles to the west of the town itself. Brigadier General John Buford’s Yankee cavalrymen had skirmished with the lead elements of Major General Henry Heth’s division of the Confederate Third Army Corps. As the butternut soldiers closed in on McPherson Ridge, less than a mile outside of the town, timely Federal reinforcements arrived. Major General John F. Reynolds, acting left wing commander of the Army of the Potomac, led Major General Abner Doubleday’s 1st Corps on the field (with Reynolds as wing commander, Doubleday had been bumped up to corps command).

Reynolds oversaw the deployment of an artillery battery along the Chambersburg Pike. He also ordered forward the vaunted Iron Brigade, an attempted to throw back the mixed Alabama-Tennessee brigade of James J. Archer. In the melee at Herbst Woods Reynolds was felled by the Confederates, who were thrown back from the woodlot. Command of the field temporarily fell on the shoulders of Doubleday More Federals were thrown into action near a railroad cut north of the Chambersburg Pike. The fighting in this sector turned into some of the deadliest fighting on the Gettysburg battlefield, fighting which we will examine in the following series.

*****

Brigadier General Lysander Cutler’s brigade was the first Federal infantry brigade to arrive on the battlefield at Gettysburg. Before the fall of Major General John F. Reynolds, the left wing commander had taken the time to deploy Captain James A. Hall’s 2nd Main Battery and dispatched elements of Cutler’s brigade to the north and south side of the Chambersburg Pike.

Hall’s six 3-Inch Ordnance Rifles were ordered “to hold the attention of the enemy until the infantry got into position.” Reynolds promised support to Captain Hall and eventually three infantry regiments were dispatched across an unfinished railroad Cut to the batteries right, in support.

Colonel John William Hofmann’s veteran 56th Pennsylvania Infantry and Major Andrew Grover’s 76th New York Infantry were the first Federal infantry to deploy north of the cut. Through the wheat field in front of him, Hofmann spied a compact group of solders driving towards his command. Col. Hofmann turned to General Cutler, who accompanied Hofmann’s men to their assigned position, and asked “Is that the enemy?” Cutler’s curt reply was “Yes.” That was all the 39 year old colonel needed to hear. “Ready! Right Oblique Aim! Fire!” Hoffman’s men unleashed the first Federal infantry volley of the battle.

Hoffman had picked a fight that the rebels were ready for.

*****

The mixed Mississippi-North Carolina Brigade of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis was a behemoth, as compared to the undersized regiments Cutler was able to field. Carrying some 1,508 men into battle on July 1st, the brigade headed by the nephew of Jefferson Davis was entering its first battle as an organized unit. The 2nd and 11th Mississippi were the only veterans units in the formation (the 11th Mississippi was on detached duty on the morning of July 1st and would have brought the brigades numbers up to 2,305). The duel Mississippi units were veterans of First Manassas, the Peninsula, and Antietam; following the latter battle the Magnolia State units were transferred to the backwater of North Carolina. For two of the regiments, the 42nd Mississippi and the 55th North Carolina Gettysburg was their first true taste of combat. The over-sized 42nd Mississippi had arrived in Richmond, in June of 1862, being mustered in as 11 companies one month earlier. The unit missed the fighting on the Peninsula, and built fortifications for the defense of the capital, rather than fight for its defense.

The 55th North Carolina was mustered in at the same time as the 42nd Mississippi, and like their Mississippi brethren missed the fighting on the Peninsula. The Tar Heel commander, Colonel John Connally, was described by fellow Confederate officer Dorsey Pender as “a most conceited fellow.” In the spring of 1863 Connally was insulted by a report written by an Alabama officer, he and Major Alfred Belo challenged the offending officer to a duel, with Mississippi rifles, at 40 paces! Each side were poor shots, and in the end, the Alabama officer apologized for the slight against Connally’s regiment.

The mixed brigade lacked competent leadership on the morning of July 1st. Their brigade commander, Joe Davis, had no military training. A pre-war lawyer, and nephew of the Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Joe had previously been passed over for promotion to general. Nepotism won out over experience, and the jurist was given one of the largest brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia. The field officers in the brigade were also lacking. Of the nine field officers going into battle on July 1st, only one actually had military training.

The 42nd Mississippi made their way from Herr Ridge and rested the right flank of the regiment on the Chambersburg Pike. The unit used the road to guide their advance. The 42nd’s front was massive, carrying from the road, across the railroad cut, into a wheat field north of the cut. The Mississippian’s aimed for the right flank of Hall’s six guns, with hopes of taking the guns in the flank, and capturing the tempting prize. The veteran 2nd Mississippi made up the center of Davis’ line, which extended the battle line northward into the wheat field. The green 55th North Carolina formed on the extreme left of the brigade.

The 55th North Carolina was the only non-Mississippi regiment in Davis’s brigade, thus an inter-unit rivalry festered. As the 55th made their way through the wheat field, they, like their Federal counterparts, were in search of the enemy. When Colonel Hoffman unloaded on his unsuspecting prey, the rebels were downhill from the bluecoats, advancing up McPherson Ridge, and at a range of about 500 yards. Two members of the 55th North Carolina were hit, both from the color guard. With that, the leader of the Tar Heels Colonel John Connally, began wheeling the regiment to the right as he realized he both outnumbered and outflanked the enemy.

By this time the nine companies of the 56th Pennsylvania were joined by the 76th New York on their right. Major Andrew Grover of the 76th did not realize that the enemy was actually in their front, even though his men were receiving volleys from the 55th N.C. and 2nd M.S. Connally kept wheeling his Tar Heels toward the Federal right flank. In the heat of battle Connally seized his regimental colors leading the men toward the two Yankee regiments. Connally’s single regiment of 640 officers and men out numbered the two combined Federal units, who could only muster 627 men. Moments later Connally was hit in the left arm and right hip, his second in command, Maj. Alfred Belo rushed to his side to check on the colonel, who admonished his junior officer to “pay no attention to me! Take the colors and keep ahead of the Mississippians.”* Belo followed his leaders advice and drove in the flank of the 76th NY. Major Grover, a pre-war Methodist minister, with a congregation in Cortlandville, New York, was killed in the onslaught. Grover’s leaderless, outnumbered, outflanked, and out gunned men wisely made for the rear.

Captain Hall’s battery was also coming under a flanking fire. Confederate skirmishers nipped at the flank of the cannoneers. “…a column of the enemy ‘s infantry charged up a ravine on our right flank within 60 yards of my right piece,” recalled Hall, “when they commenced shooting down my horses and wounding my men.” Artillery fire rained down from Herr Ridge to the west. Nearly twenty southern cannon had come online, ably commanded by Major William Pegram. Hall pumped canister into the infantry, while lobbing shells toward Pegram’s gunners.

Hall ordered his men from the field. He attempted to cover his retreat by pulling his right section, under Lieutenant William Uber, back to a small ridge about 80 yards to the east. Uber was unable to come on line. One of Uber’s guns lost all of the horses and had to be wheeled by hand off the field. The remaining gun was also extracted.

Apparently unsupported, Hall gave up the fight and ordered the remaining four guns off the field. Hall described the withdraw as “hellish.” Hall was able to get three of the four guns to the rear, but Confederates swarmed the last gun, shooting and bayoneting the horses. The gun had to be abandoned. Hall sought out division commander James Wadsworth and gave the officer an earful. Wadsworth had more pressing matters on his hands than a peevish artillery officer, and ordered Hall to get his guns to the rear. Hall’s men lost 2 men killed and 18 wounded, out of 119 engaged. The battery also lost 28 horses.

At about the same time that Belo was driving his attack home north of the cut, and Hall was withdrawing to the rear, a new Federal regiment arrived on the north side of the railroad cut. The 147th New York, known as the “Oswego Regiment” carried 380 officers and men into the fight. Organized in late September of 1862, the 147th New York had yet to see combat, yet their numbers were below 400, mainly due to disease. The Empire State men were late to the battle north of the railroad cut, since their commander Lt. Col. Francis Miller marched the men with Cutler’s other two regiments to the area near the McPherson Barn. To rectify the situation, Miller’s men set off at the double quick to protect Hall’s flank. Two companies moved forward to a small crest and witnessed both the fall of Hall’s battery, as well as the sea of butternut soldiers that awaited them. There was little these two companies could do, Hall was on his own.

When the 147th came on line they anchored their left flank on the cut itself, but their right flank was in the air. When Miller brought the unit on line, he did so 150 yards in front of the 56th Pennsylvania and 76th New York, thus the New Yorkers were unsupported and exposed. The bullets flew thick and fast and the New Yorkers were now tangling with both the 42nd and 2nd Mississippi whose combined strength totaled 1,067 officers and men. The Magnolia State soldiers engulfed the front and right flank of the Empire State men. The New Yorkers “were falling like autumn leaves; the air was full of lead.”

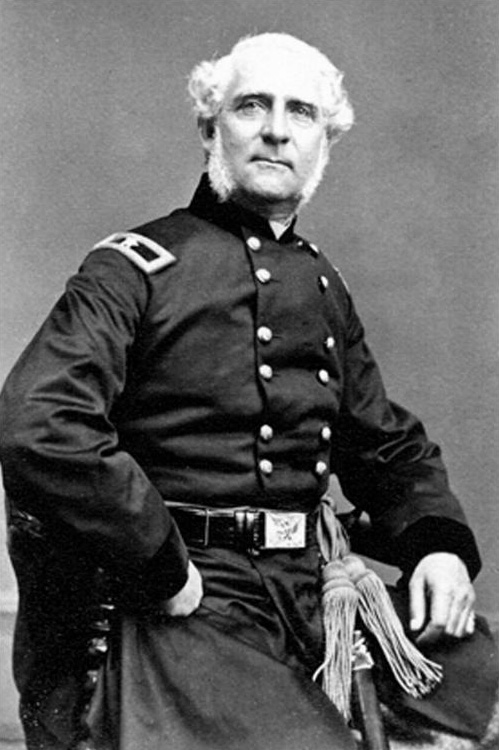

Belo’s Tar Heels finished off the 76th New York and 56th Pennsylvania; and now set their sights on sealing off the retreat route of the 147th New York. Brigadier General James Wadsworth, the division commander of the 147th saw the pending doom of his fellow New Yorkers. The 55-year-old Wadsworth defied convention. He was not a West Point graduate, nor was he a career politician like many other generals; he was actually a millionaire New Yorker from Geneseo, who had answered his country’s call to arms and had even refused pay for his service.

Prior to the war, Wadsworth had studied law at Harvard and dabbled in politics. During the First Manassas campaign, he proved a capable volunteer staff officer to Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell. The following month, in August of 1861, Wadsworth was promoted to brigadier general and held the post of military governor of Washington D.C. In 1862, while serving in the army, he ran for New York’s governorship but lost.

“Wadsworth has never done anything in his military capacity to deserve credit,” lamented Robert Robertson of the 93rd New York. “He has never taken the field nor exposed his life in the country’s service, but the sphere of his duties are confined to Willard’s Hotel and a comfortable office, so what has he done.” Wadsworth had much to prove.

He commanded the 1st Division, 1st Corps at the battle of Chancellorsville. During the opening stages of the battle his division was ordered across the Rappahannock River in boats.

As the boats made their way across the river, Wadsworth leapt into action. Reynolds’s staff officer, Charles Veil, claimed that the white-haired general “jumped his horse off the bank and swam the river with the men. His son, Captain [Craig] Wadsworth, who was an aide on General Reynolds’ staff, seeing what his father was doing, put spurs to his horse and, too, plunged into the river and swam over after his father.”

Wadsworth quickly grasped the situation and dispatched orders for the 147th New York to retreat. One of Wadsworth’s aides approached Lieutenant Colonel Miller and delivered Wadsworth’s message. As Miller turned to order the men out he was shot in the head, and his horse carried him to the rear, before he could deliver the command to retreat. Not knowing of the retreat orders, Miller’s second in command, Maj. George Harney, stood to the task of holding off the rebels. The color bearer of the regiment Sgt. John Hinchcliff, “a Swede, six feet two, fair haired, blue eyed,” went down. Sgt. William Wybourn extracted the flag from under the Swede’s body. Confederates nipped at the right flank of the regiment and Harney ordered the three right flank companies to refuse the line.

After a few minutes, Wadsworth noticed that the New Yorkers still were fighting tenaciously north of the cut. The white haired officer sent another staff officer to order them out. This time the order was received and executed. Harney gave the order “In retreat, double-quick, run!” Some of the men ran due east towards the McPherson’s Woods along Oak Ridge (Authors note: There woods should not be confused with the Herbst Woods, known incorrectly by many as McPherson’s Woods, where Reynolds fell. McPherson’s Woods on Oak Ridge are better known today as Sheads Woods) and Cutler’s other two regiments that had been roughly handled by Davis’s brigade. Others attempted to make their way down the cut towards the town, but Confederates had trapped them in the cut by “throw[ing] up a barricade of rails…” some 30 rods down the cut. “Many of our men perished before they could get out…” Others, “climbed up the rocky face of the [rail road] cut…” and made their way to safety.

Sergeant Wybourn, with the flag of the 147th made for safety, as he did he “received a shot, and fell on the colors as if dead.” Lieutenant J. Volney Pierce tried to remove the flag from the dead sergeant, who would not let go of the flag. The lieutenant ordered the Irishman to relinquish the flag to which he responded “’Hold on, I will be up in a minute,’ rolled over and staggered to his feet and carried them all through the fight…”

The 147th, which entered their first battle with 380 men, lost 296 of those engaged, 78% of their fighting strength. As the survivors of the regiment streamed to the rear they passed General Cutler, who was clearly angry from being bested by Joe Davis’s men. “You have lost your colors, sir.” Cutler growled at Major Harney. Proudly Harney pointed toward Sgt. Wybourn, who was struggling to get off the field, and declared “General, the 147th never loses its colors.” Sheepishly Cutler said “I take it all back….It was just like cock-fighting today. We fight a little and run a little. There are no supports.” Luckily for Cutler he was wrong and support was on its way.

*On July 1st Connally was felled by two shots, one to his right hip, the other to his left arm. Due to the wounds, Connally had to be left behind as the army retreated to Virginia. He was captured by Federals and one of their surgeons amputated his left arm. He was paroled in March of 1864 but unable to take to the field again. In the past war years Connally moved to Texas and then to Virginia, where he served in the state legislature, becoming the youngest man to be elected to the state senate. On April 27, 1870 the third floor of the Virginia state house collapsed into the Hall of House of Delegates below. In the “great disaster” 61 people were killed and 251 injured. Amazingly Connally survived this tragedy, living to the age of age 64.

Connally’s second in command, Major Alfred Belo almost became a captor of the Federals himself. While trying to make his way out of the railroad cut and back to Herr Ridge, a Federal swung a sword at his head, nearly hitting him, he and a number of the 55th were able to scramble to safety.

Be sure to check out Fight Like the Devil: The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863; authored by Chris Mackowski, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis.

I don’t think I have ever seen that photo of Wadsworth before, believe it or not. I always felt he was underappreciated.