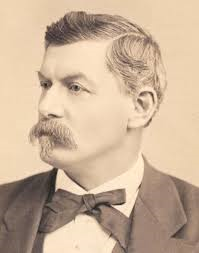

Seldom Has This Community Been Universally Shocked: New Jersey Newspapers React to the Passing of George McClellan

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author William Griffith.

This past December, for my twenty-third birthday, I did what any normal person my age would do – or at least I tell myself this – and made a cemetery pilgrimage. My destination this year was Riverview Cemetery located in the heart of Trenton, New Jersey along the Delaware River. Originally incorporated in 1858, the cemetery is home to the final resting places of several notable Civil War personalities including Randolph Marcy, Gershom Mott, and William Truex. Riverview’s most famous “resident” however, is none other than George Brinton McClellan.

After seeing the imposing monument that towers over Little Mac’s gravesite – and the rest of the cemetery for that matter – my curiosity was sparked and I began to ask myself a series of questions. Although a son of Pennsylvania, McClellan made his home in West Orange, New Jersey during his post-Army of the Potomac days in 1863 and owned a farm that stretched from Mt. Pleasant Avenue to Northfield Road. Although not politically supported in the 1864 election by his hometown due to his party affiliation – West Orange actually went with Abraham Lincoln – he nevertheless won the state and quickly became one of New Jersey’s favorite adopted sons.

Following his failed campaign for the presidency, McClellan fled the country in “exile” to Europe before returning home to West Orange and winning the 1878 New Jersey gubernatorial election on the democratic ticket. According to biographer Stephen Sears, McClellan’s term as governor was “marked by careful, conservative executive management and minimal political rancor.” When he completed his three years in office, the ex-general remained an active supporter of his party and finished his memoirs of his service during the war only to have them destroyed in a warehouse fire while he was vacationing in Europe. After concluding his oversea adventures for the final time, he returned home to New Jersey where he died of a heart attack on October 29, 1885. He was just fifty-eight years old.[1]

Death came suddenly and unexpectedly to George McClellan, but after spending over twenty years in New Jersey, winning the state during the election of 1864, serving as governor for three years, and remaining an active member in the church and his community until his passing in 1885, what was the legacy he left behind? How did the citizens of his adopted home react to the news? Did political party tension shape the way he would be remembered.

Following my pilgrimage to Mac’s grave I wanted to know the answers to these questions. In order to do so, I figured the best way would be to venture to the New Jersey State Archives in Trenton and begin digging through the thousands of microfilm reels filled with contemporary periodicals. Examining both republican and democratic newspapers, a postwar image of a beloved general was formed that I hadn’t seen before.

On October 30, 1885 – just a day after McClellan’s death, the staunchly democratic New Brunswick Daily Times published a very spicy, but sincere ode to the general defending his name and legacy. The opening of the article read:

“Seldom has this community been universally shocked as it was yesterday, on the announcement of the death of General George B. McClellan. Few that knew him did not love him, and he enjoyed the respect of all whose opinions were of any importance. None decried him except the hide-bound politicians of a party who did their best for over twenty years to slander and underrate his abilities and the work he accomplished against such great odds. As years roll on it will be brought more and more to the front how great was the ingratitude of the late President Lincoln and his Cabinet. After the rebels had driven the incompetent John Pope and the United States army ingloriously across the Potomac into Washington, then the President and his Cabinet, terror stricken, fell upon their knees and begged of the man whom they had been endeavoring to disgrace to save them and the country. And General McClellan then as always was a true patriot.”[2]

Although the other papers that I examined did not openly express the “ingratitude” of Lincoln and his cabinet, the Monmouth Democrat was certainly not afraid to denounce the criticisms of McClellan’s military peers and place him on the pedestal that the rank and file held him high upon:

“Space will not permit any extended history of General McClellan, nor is it necessary that any should be written, for it is printed ineffaceably in the hearts of his countrymen … He was a silent man, and bore patiently and without a murmur the unjust criticisms of civilian generals whose pens were mightier than their swords. History will make straight the record that some have twisted and distorted to the hurt of General McClellan … It is safe to say that no one of the Union officers held so firmly the affection of the rank and file as did General McClellan. He won them to him by his love for them.”[3]

The West Jersey Press, too, expressed the affection and respect of the troops that the general had earned and cherished so dearly:

“General McClellan was a man of honest, generous impulses, possessed of scholarly attainments … and probably the finest military engineer in the country. As a soldier he was not a success in the position to which he was assigned, but his solicitous care for the comfort and health of the men under him won their everlasting regard and rendered him probably the most popular of all the commanders of the Army of the Potomac … He undoubtedly made what he considered the best use of his opportunities, and if he did not achieve all that was expected of him it was through no fault of his that he could remedy.”[4]

In an effort to defend McClellan’s legacy and reputation – which was very much in question following his death – the Clinton Democrat published an interview with one of his most loyal subordinates, Fitz John Porter:

“In General McClellan’s case every statement is conclusively proven. The publication of [his personal memoirs] is necessary to General McClellan’s reputation, and, furthermore, it will set right many errors in history and do away with many apprehensions.”[5]

Unfortunately for the “Young Napoleon”, the botched compiling and editing of McClellan’s Own Story by William Prime, published in 1887, only fueled even more controversy surrounding the general’s life than had already been stirred up.[6]

With seemingly all of the democratic newspapers in New Jersey fighting to defend their beloved Little Mac’s reputation, what did the other side of the political spectrum have to say? In truth, after examining a handful of republican periodicals, I found that not much regarding his role in the Civil War or as a politician was said. Besides the standard obituary giving a brief description of his birth, life, and death that was reprinted in nearly every republican issue, the only insight given into his army days was simply that “His early military career was more successful than his later one,”[7] Even his hometown’s republican-driven Orange Journal did not touch upon his Civil War service or political career. It would not be until the publication of McClellan’s memoirs that many republicans began to take a stance against the late general. The civilian democrats certainly fought harder to preserve McClellan’s legacy than the republicans did to taint it upon his passing. Even the political enemies of his party could not disrespect what the general had meant to the state and its populace.

The battle for George McClellan’s legacy is still being fought today by historians and students of the Civil War. The fight between the anti-McClellan school of thought and the McClellanites rages with new and traditional interpretations being wielded as weapons. One-hundred and twenty-nine years following his death, George McClellan’s Riverview Cemetery monument still looms high above the Delaware River commanding attention by all who see it, and so, too, does his memory.

[1] Stephen Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (New York: De Capo Press, 1988), 397.

[2] “Death of General McClellan,” New Bruswick Daily Times, October 30, 1885.

[3] “Little Mac,” Monmouth Democrat, November 5, 1885.

[4] “General George B. McClellan,” West Jersey Press, November 4, 1885.

[5] “General McClellan’s Memoirs,” Clinton Democrat, November 13, 1885.

[6] Sears, George B. McClellan, 403-406.

[7] “Death of Gen. McClellan,” The Jerseyman (Morristown, NJ), October 30, 1885.

I really appreciate the insight into the political rancor that raged in those days. Thank God we are over that now!

I wonder if and how the postbellum nation, and especially the South, would be different today had Little Mac not taken counsel of his fears and been able to crush the Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg. Perhaps the tens of thousands of military deaths after Antietam and the economic ruination/destruction of the civilian South were necessary precursors to a reconstructed nation. Maybe Harry Turtledove or the Gingrich/Fortschen team could write a book about that historical scenario.

Once can excuse military losses. But his treatment of President Lincoln, particularly the time he refused to come downstairs to meet him, and his disrespect of the Commander in Chief, is Little Mac’s lasting legacy.

I agree, Ed. The contempt with which he treated Lincoln was inexcusable. He didn’t have to like the guy, but he had to respect his authority–which he only barely did.

Perhaps, John GIll, slavery would have continued indefinitely

And I think that possibility sealed the fate of the CSA, and rightly so.

Why was he buried in Trenton if he lived in Orange?