The Capture of Jefferson Davis, part two

Part two in a series

After his meeting with Colonel Henry Harnden of the 1st Wisconsin on May 9th, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Pritchard took his 4th Michigan troopers to Abbeville Georgia. His assigned mission was to picket the crossings of the Ocmulgee, and he established a camp outside of town for that purpose. There was no guarantee that Harnden’s quarry would actually turn out to be the Davis party, and if so, the river still needed to be watched. At that time, Pritchard later reported, “there was no plan of action agreed upon between Colonel H[arnden] and myself, as neither of this knew anything about the roads” in the vicinity.

That soon changed. Two miles beyond (south of) Abbeville, recalled Julian G. Dickinson, the 4th Michigan’s Adjutant, the Wolverines met an “aged colored man” trying to fix a “broken-down vehicle.” Upon being questioned by Pritchard, once again a newly-freed slave proved a font of information. A mounted party had indeed crossed the Ocmulgee at the Abbeville Ferry, having “paid [for their crossing]. . . in gold coin,” and “all the men had fine horses and equipments.” Further, there were two roads to Irwinville, the direct route taken by the 1st Wisconsin; and a round-about way that followed the river south for a dozen miles before turning to approach Irwinville from the east.

That soon changed. Two miles beyond (south of) Abbeville, recalled Julian G. Dickinson, the 4th Michigan’s Adjutant, the Wolverines met an “aged colored man” trying to fix a “broken-down vehicle.” Upon being questioned by Pritchard, once again a newly-freed slave proved a font of information. A mounted party had indeed crossed the Ocmulgee at the Abbeville Ferry, having “paid [for their crossing]. . . in gold coin,” and “all the men had fine horses and equipments.” Further, there were two roads to Irwinville, the direct route taken by the 1st Wisconsin; and a round-about way that followed the river south for a dozen miles before turning to approach Irwinville from the east.

With this information in hand, Pritchard now decided to head towards Irwinville himself. The bulk of the regiment would continue to picket the river, but Pritchard, Adjutant Dickinson, Captain Charles T. Hudson, 5 other officers and “128 of the best mounted men” would run down this lead. Most everyone now knew that the quarry was Davis, and, Pritchard reported, a number of men joined the column “irregularly,” not wishing to be left out of the potentially lucrative excitement. Departing Abbeville at 1:00 p.m., Pritchard’s expedition first rode south for 12 miles, paralleling the river as far as a place called Wilcox Mills. There they halted for a short rest and a meal, but that was all. At dark, Pritchard turned westward towards Irwinville. With luck, thought Pritchard, his column and Harnden’s force might catch Davis between them.

As noted, the Davis party made only slow progress on the 9th, and went into camp a mile north of Irwinville at about 5:00 p.m. Initially, Davis intended only to eat and catch a brief rest before riding on through the night, but with both horses and men becoming increasingly frazzled, this proved impossible. Then Colonel William Preston Johnston (son of the late General Albert Sidney Johnston of Shiloh fame, serving as one of Davis’s military aides) went into Irwinville seeking supplies, only to return bearing more tales of “roving bands of lawless renegades,” searching for the Davis party, and presumably for the last of the Confederate gold. Davis elected to stay with his family for the night.

Meanwhile Colonel Harnden, oblivious to Pritchard’s presence, also chose to call a halt at dusk, upon finding “a swale where there was water and a little grass.” Harnden, aware of the creek ahead, correctly divined that the Davis camp would lie on the far side of that stream. “[I] had only halted so as not to come upon them in the night,” he later explained. “I thought if we attempted to cross the ford in the dark, Davis would take the alarm and escape.”

Pritchard made no such camp. He expected to be well behind both Davis and Harnden, since his chosen route was at least 8 or 9 miles longer than Harnden’s direct road and the Wisconsin officer had at least a two hour start on him. Much to his surprise, when Pritchard led his Wolverines into the tiny hamlet at 1:00 a.m. on the 10th, the found neither Davis nor the 1st Wisconsin. “Irwinville was then a place of a half dozen dwellings,” noted Dickinson, “a sort of four corners in the wilderness.” The residents were grudgingly roused, with the Michiganders taking care to identify themselves as Confederates so as to encourage shy tongues to wag. They had no luck. The locals remained closed-mouthed, fearing even to step outside their doors.

Once again, a newly-freed slave was more than happy to talk. This servant told Pritchard all about the man who had come into town seeking eggs and other provender (Colonel Johnston’s shopping trip) as well as the camp of wagons and tents pitched a mile and a half north of town on the Abbeville Road. Clearly this was not the camp of the 1st Wisconsin – they had neither tents nor wagons.

By now, sunrise was not far off. Pritchard detailed 25 men to circle around the suspect camp and take up position astride the road back towards Abbeville, preventing Davis’s escape to the north. A similar force under Captain Charles T. Hudson would lead the first dash into camp at first light, quickly followed by Colonel Pritchard and the main body of the 4th Michigan.

Harnden also intended to surprise his quarry at dawn. The 1st Wisconsin roused well before first light on the morning of May 10th. Sergeant George Hussey and an advanced squad of six men led that column southward.

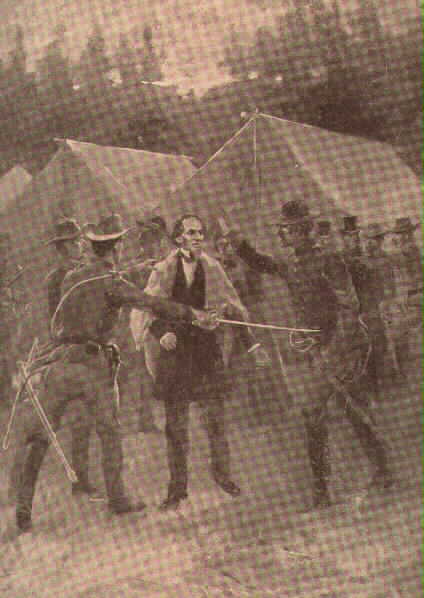

The Wolverines struck first. Hudson’s platoon rode straight into Davis’s camp, “uninterrupted by any picket of camp guards. . . .” The surprise, noted Dickinson, was “so complete that no one seemed to have been disturbed.” The Davis’s black coachman, James Jones, was the first to raise the alarm. The morning stillness was broken by first one shot, then a ragged volley. Jones ran to warn Davis, who at first thought the interlopers must be the expected renegades, not Federal cavalry. He was soon persuaded otherwise.

Davis was conflicted. He was fully dressed, except for his boots and his own coat, but he hesitated to leave Varina and the children. He now reasoned that if the newcomers were indeed Federals, then the danger posed to his family was lessened. Accordingly, after a moment or two, and while the camp was still in turmoil, Davis donned a convenient cloak (a waterproof Raglan) and made for the nearest cover, swampy ground along the creek 100 yards distant. As he departed, Varina threw her black shawl over his head as further disguise.

The cloak, it turned out, was also Varina’s, grabbed in haste; that particular combination of cloak and shawl would plague the proud Mississippian for years to come.

Corporal George Munger of the 4th Michigan was the first to approach the Davis’s tent. Varina tried to distract him while the president walked slowly towards the swamp. Dickinson recalled that Andrew Bee, a cook for the regimental headquarters, called his attention to the walking figure. “There goes a man dressed in women’s clothes!” Davis was discovered. Munger raised his carbine, but Dickinson intervened, “there being no perceptible resistance.” Davis was captured.

Though none of the officers with Davis offered any resistance, the sounds of firing could still be heard, however, north of camp. Harnden’s Wisconsinites had arrived on the scene.

Sergeant Hussey’s patrol and collided with the 25-man Wolverine picket on the Abbeville road. In response to a low-voiced challenge, Hussey responded ambiguously. “Friends,” he replied. A shot rang out, then a ragged volley, as both groups opened fire.

Things almost developed into a pitched battle. Harnden ordered half of his men to dismount and deploy. Hussey, after absorbing several volleys (Harnden estimated three) fell back on the main line, some of his men wounded. With the camp and quarry secure, Colonel Pritchard rode north with the remainder of his column, roughly 100 men; a movement which Harnden interpreted as an effort to outflank his own force. In response, Harnden ordered Lieutenant Orson Clinton to counter-charge. In the meantime, Harnden’s dismounted skirmishers were emptying their Spencer repeating rifles at the Wolverines.

Then Hussey reappeared. “They are Union men,” he said. Nonplussed, Harnden turned to him, and the sergeant explained that he had captured one of the Michiganders. With that, the fight was over. Harnden ordered his men to cease fire, shouting that they were Federals; Pritchard, realizing what had happened, did likewise. Still, the action was not without cost. The 4th Michigan suffered two killed and several wounded, while Harnden’s casualties amounted to three wounded.

Harnden was stunned by Pritchard’s unexpected presence, so much so that initially he failed to recognize the other officer. Once Pritchard explained, Harnden asked if they had captured Jefferson Davis. “he did not know . . .” explained Pritchard, “as he had not been to the camp himself.”

Davis had indeed been captured, as had Postmaster General John H. Reagan. Harnden recalled that he and Pritchard rode up to Davis,”dismounted and saluted, and I asked if this was Mr. Davis. ‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘I am President Davis.'” All around them, the troopers from both Union regiments now buzzed with excitement and jubilation. Some of them began to sing, “we will hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree,” which, noted Harnden, “did not add to his comfort in the least.”

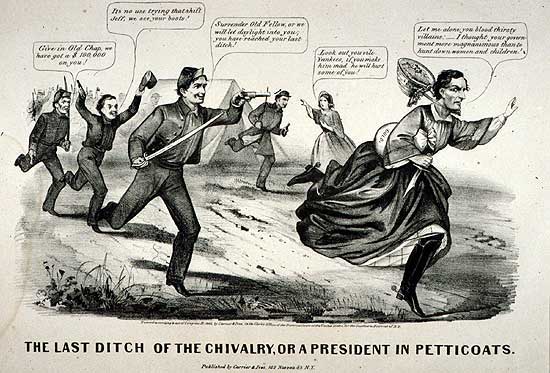

Davis would be escorted northward, imprisoned at Fort Monroe Virginia until he could be tried for treason. The news of his capture raced across the country. The details of the cloak and shawl were seized upon by a gleeful northern press, who soon were mocking him unmercifully for trying to escape in women’s clothing. Cartoons pictured him in dresses and petticoats. Even Edwin Stanton requested that one of Varina Davis’s dressed be sent north along with the captured Confederate executive. The tale, of course, was grossly exaggerated beyond all recognition, but Davis would be forever living it down.

Davis would be escorted northward, imprisoned at Fort Monroe Virginia until he could be tried for treason. The news of his capture raced across the country. The details of the cloak and shawl were seized upon by a gleeful northern press, who soon were mocking him unmercifully for trying to escape in women’s clothing. Cartoons pictured him in dresses and petticoats. Even Edwin Stanton requested that one of Varina Davis’s dressed be sent north along with the captured Confederate executive. The tale, of course, was grossly exaggerated beyond all recognition, but Davis would be forever living it down.

To be continued…

Great story – I always enjoy reading what I can about Julian G. Dickinson. — B. Dickinson