The Port Royal Experiment-Setting the Stage for Reconstruction, Part 4

Conclusion to the Port Royal Experiment series.

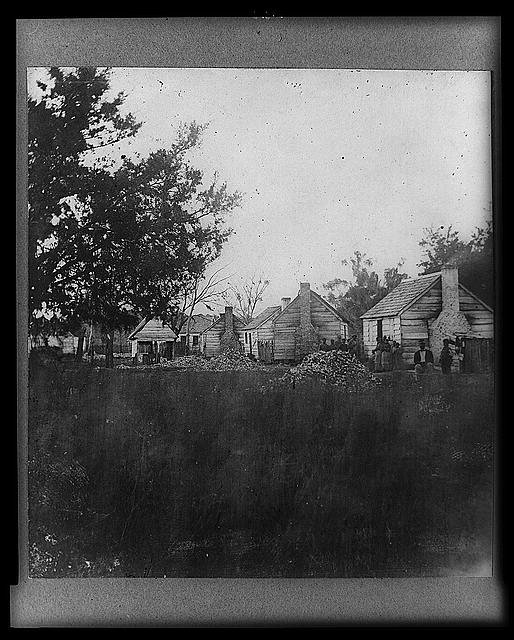

![[Detail] - Cotton ready for the gin at Smith's Plantation in Port Royal, South Carolina.](http://emergingcivilwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/port-royal-cotton.jpg?w=300)

Despite the preparation, the enthusiasm, and the progress of the Gideonites based in Port Royal, South Carolina, the government had separate ideas for how Reconstruction should be structured. Educationally, the experiment was a success. Economically and socially, however, the project contained significant flaws.

By the end of 1863, many of the relief committees created to support the African Americans in Port Royal, published favorable reports illustrating the success of the experiment. Stephen Colwell, a Port Royal Relief Committee member, wrote the following:

“The freed blacks there, now 15,000 in number, are a self-supporting, wealth-producing people. They are orderly in their behaviour, and are rapidly rising in the scale of intelligence. The able-bodied are serving their country as soldiers, while the less robust are making themselves equally useful in cultivating the fields. Some of the younger ones, who two years ago came into the schools in a condition of absolute ignorance, are now competent to take the part of assistant teachers.” [i]

While the project contained significant advances in the overall welfare of the African Americans in Port Royal, several issues arose. Despite all of the efforts of the Gideonites and other abolitionists, the former slaves were still seen as inferior by everyone outside the Port Royal bubble. Tradesmen sold goods at higher prices, knowing both the African Americans and the Gideonites had no other option. Clothing and other non-perishable items were sent from Northern abolitionists when possible, but the majority of the time, the Gideonites needed to use merchants on the mainland in order to purchase supplies. Even after the war was over, Laura Towne remarked that “there is no abatement in prices yet here,” when commenting on the high price of soap and brown sugar.[ii] This extortion was just the start of the social problems African Americans would face after the end of the war. Even though the Gideonites provided the moral, social, and scholarly education, the barriers between whites and blacks had been created when the first Africans set foot on the North American continent in 1619.

When the project at Port Royal started, the economics focused on turning a profit for the government through harvesting cotton. In their eyes, helping the African Americans gain a way of life came secondary. Despite this, Pierce still pushed that for the experiment to be successful, the former slaves needed land and sense of propriety in order for the re-integration to work. First, however, Pierce needed to convince the African Americans to continue their work on their plantations harvesting cotton after their masters had fled. The former slaves preferred to harvest corn, and grow their own vegetables, since the constant reassurances of payment fell through as the months passed, and “their corn…saved them from starvation.”[iii] Laura Towne commented on this soon after she arrived in Port Royal:

“I think it is very touching to hear [the African Americans] begging Mr. Pierce to let them cultivate corn instead of cotton, of which they do not see the use….They do not understand being paid on account, and they think one dollar an acre for ploughing, listing, or furrowing and planting is very little, which of course it is….Nothing is paid for the cultivation of the corn, and yet it will be Government property. The negroes are so willing to work on that, that Mr. P. has made it a rule that till a certain quantity of cotton is planted they shall not hoe the corn.”[iv]

Aiming to relieve some of the issues with the cotton and corn harvests, Pierce lobbied for the sale of confiscated Confederate lands in the Port Royal area to African Americans. In early 1863, the government planned to sell 21,000 acres out of the 80,000 confiscated lands in Port Royal for a dollar an acre. A large chunk had been set aside for charity and military uses. So soon after the project started, the push for African Americans to purchase land had not been fully developed. Nor did the former slaves have the wealth to purchase vast amounts of land. Split into 20 acre lots, this first sale was targeted more toward wealthy Gideonites and Northern sympathizers. Encouragingly, a small portion of the 15,000 African Americans in the Sea Islands purchased around 2,000 acres. The other 19,000 acres transferred to wealthy Northern Gideonites such as Edward Philbrick, who alone purchased around 7,000 acres. In the fall of 1863, an additional 40,000 acres was to be sold, with 16,000 reserved for African Americans. This sale became more complicated, as government agents in charge of the sale created a complicated buy-in and survey system, drawing out the process of selling land to the African Americans. By the end of the war the Federal government had sold only 6,000 acres to former slaves.

The hope the Northern missionaries had of the reintegration being successful ended with the death of Abraham Lincoln in April of 1865. Instead of using the accomplishments of the Port Royal experiment, Andrew Johnson upheld states’ rights, allowing each state to decide upon the course of action concerning African Americans. Additionally, Johnson reinstated land to Confederates who took an oath of loyalty to the Union. As a result, these pardons allowed Confederate leaders to regain control of their pre-Civil War positions, including within the government. States enforced Black Codes, creating hardships and unnecessary difficulties for African Americans. Although Johnson continued to support Lincoln’s emancipation of the slaves and the abolition of slavery, he felt that the former slaves were unable to manage their lives, and continually thwarted plans to improve African American’s rights.

On a small scale, the Port Royal experiment illustrated the successful reintegration of former slaves into a working and profitable society. With the help of understanding and caring individuals like Edward Pierce, Laura Towne, and Charlotte Forten, the African Americans in Port Royal were able to thrive; however, removing the plantation system and providing limited opportunities for land ownership highlighted the social rifts between whites and blacks. Attempting to expand the ideals laid out in the Port Royal experiment to the other 3.5 million slaves outside the Sea Islands– in a hostile, racist, and unforgiving Southern environment with a Southern sympathizing president – proved extremely difficult, allowing Reconstruction to fail under Andrew Johnson.

[i] Stephen Colwell, “Port Royal Relief Committee Early History,” Pennsylvania Freedmen, 1865.

[ii] Laura Towne, Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne, Rupert Sargent Holland, ed., Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1912, 166.

[iii] Laura Towne, Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne, Rupert Sargent Holland, ed., Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1912, 18.

[iv] Ibid., 18.

Bibliography

Colwell, Stephen. “Port Royal Relief Committee Early History,” Pennsylvania Freedmen, 1865.

Towne, Laura M. Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne. Rupert Sargent Holland, ed. Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1912.

Ochiai, Akiko. The Port Royal Experiment Revisited: Northern Visions of Reconstruction and the Land Question. The New England Quaterly, Inc., 74, no. 1 (March 2001): 94-117.

This is a particularly timely article. I hope we have more posts about the 150th anniversary of Reconstruction. This is where remembrance really needs to kick in. Thanks, and I personally thank you for including your sourcework.