The Wounding of Stonewall Jackson

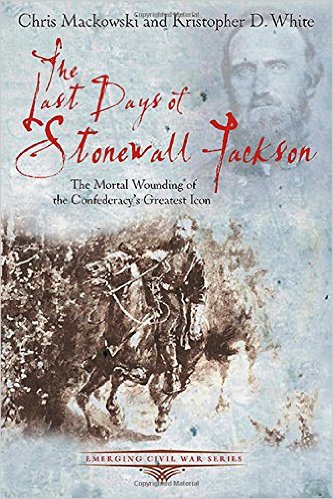

The following is a chapter excerpt from the revamped “Last Days of Stonewall Jackson,” authored by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White. The wounding site of Stonewall Jackson will be one of the stops on the upcoming Emerging Civil War tour of the Chancellorsville Battlefield, which is part of the Second Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium at Stevenson Ridge, August 7-9.

The following is a chapter excerpt from the revamped “Last Days of Stonewall Jackson,” authored by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White. The wounding site of Stonewall Jackson will be one of the stops on the upcoming Emerging Civil War tour of the Chancellorsville Battlefield, which is part of the Second Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium at Stevenson Ridge, August 7-9.

*********

Several hundred yards to the south of the Orange Plank Road, a Pennsylvania unit, the 128th Infantry, had stumbled through the dusk quite by accident into the main Confederate line. Running into unfriendlies in the tangled Wilderness was bad enough on the nerves, but the appearance of the Pennsylvanians discomfited the Confederates all the more because it seemed the Keystoners had somehow slipped past the skirmishers that had been posted forward. Realizing their blunder, the Pennsylvanians tried to escape, but the Confederates took a large number of them as prisoners.

Word of the incident spread along the Confederate line: Union troops wandering through the darkness were liable to appear at any time and at any place.

Already skittish, Confederates began shooting at shadows. One jumpy Confederate would infect the man next to him—who would, in turn, spook the man next to him. The shooting intensified and, like a wave, began moving northward along the entire Confederate line—right across Jackson’s front just as he and his men returned down the Mountain Road from their reconnaissance mission.

The initial volley shot the horse out from under one of Jackson’s staff officers, Lieutenant Joseph Morrison, the general’s brother-in-law. Morrison immediately leaped to his feet. “Cease firing!” he yelled. “You are firing into your own men!”

A veteran unit, the 18th North Carolinian had heard it all. They knew the tricks. And, after all, hadn’t the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry been caught behind Confederate lines just a couple hours earlier? Hadn’t Union infantry units been captured wandering around lost between the lines? And weren’t these horsemen—probably cavalrymen—coming from the direction of the Union lines? All the evidence pointed toward a Federal ruse.

“It’s a lie!” responded Major John Barry. “Pour it into them, boys!” By this time, the North Carolinians had had time to reload. They cut loose with the power of a full, concentrated volley.

The darkness and density of the forest protected most of Jackson’s men, although a bullet killed staff officer William Cunliffe. Another staff officer, Joshua Johns, was wounded. The others escaped unscathed— except for Jackson himself. Three bullets struck him: one in the right hand, one in the left forearm, and one three inches below the left shoulder.

Little Sorrel bolted in panic. Jackson, barely able to stay on, held up a hand to protect himself as the horse plowed through the underbrush. A thick branch hit Jackson in the face, nearly knocking him to the ground. With effort, he began to rein in Little Sorrel enough so that his staffers could come to his aid. “General, are you hurt?” they inquired. “I fear my arm is broken,” he replied. He also complained of a slight wound in the right hand. “All my wounds are by my own men,” he marveled.

As his aides tried to ease him from his saddle, Jackson collapsed onto one of them. They then lowered him the rest of the way and began to examine the wounds. Meanwhile, Little Sorrel, still panicked, tore away again, bolting eastward through the forest. Riderless, he would gallop through the Union line and be captured. Jackson was not the only general caught in the cascading musketry.

Out on the Plank Road, which ran parallel to the Mountain Road fewer than thirty yards to the south, A. P. Hill had gone forward with a reconnaissance party of his own. As the commander of the reserve division coming onto the battlefield, Hill knew it would be up to him to carry forward any attack, should Jackson order one. Unfortunately, he had no David Kyle serving under him, no local guide who knew the ground, so Hill had taken it upon himself to familiarize himself with the terrain. He and his nine men, far more exposed on the wider road and well-lit by the full moon, were caught in the open when the “rolling thunder” rolled by. All of Hill’s men were killed or wounded or had their horses panic and bolt toward the Federal line. Hill, untouched, survived by diving to the ground.

The division commander quickly recovered and was among the first on the scene to help Jackson. He and Captain Richard Wilbourn pulled off Jackson’s gloves, stripped away his heavy India-rubber raincoat, and tore open his sleeves to examine the wounds. They applied bandages, made a sling for the left arm, and waited for help to arrive.

* * *

The firing along the Confederate line had not gone unnoticed by the Federals, who soon opened up an artillery bombardment now that they had an approximate idea of the Confederate position. One Federal gun unlimbered in the middle of the Plank Road only a few hundred yards away from the fallen Jackson.

As if to underscore the proximity of the enemy, two Union soldiers wandered into the small clearing where attendants were bandaging the general’s wounds. “Take charge of those men!” Jackson barked. Before the Federals could take in the situation, Confederate soldiers took them prisoner. But where there were two Union soldiers, might there not be more? Jackson’s staff members quickly decided it was time to move.

As they tried to carry him away from the front, Jackson worried that news of his wounding would impact the morale of his men. “I will try to keep your accident from the knowledge of the troops,” Hill said to him. Jackson instructed other members of his party to keep the secret, as well. “When asked, just say it is a Confederate officer,” he instructed. Curiosity seekers from the ranks abounded. Soon, a litter party arrived. They laid Jackson on the stretcher, hoisted him to shoulder height, and began to move more quickly. According to one witness, Jackson remained calm the entire time, “and did not utter a groan.”

The Union bombardment intensified. “The whole atmosphere seemed filled with whistling canister and shrieking shell, tearing the trees on every side,” Morrison later wrote. The litter party moved less than fifty yards when a piece of flying metal hit one of the lead stretcher bearers, forcing him to drop the front left corner of the litter, pitching Jackson to the ground from shoulder height. Jackson landed on his wounded shoulder. After waiting out the artillery fire for a few minutes,

Jackson’s staffers scooped him up and carried him away. Soon, they recruited enough men for a second litter party. As they pushed through the thick underbrush, one of the bearers became entangled in a grape vine and tripped, dumping the litter again.

The initial gunshot wounds, while painful, had not caused an excessive amount of bleeding. Now, as the result of one of the litter accidents, the artery in Jackson’s left shoulder began to hemorrhage.

Things looked more grim than ever. A renewed urgency gripped Jackson’s men. They again placed him on the litter and carried him a few hundred yards. In their wake, word spread among the men of Jackson’s command that some terrible accident had befallen their leader in the dark woods of the Wilderness.

“Engulfed in the midst of that gloomy thicket, surrounded with so much suffering and death, with the mournful and continuous cry of the plaintive whippoorwill, made the scene inexpressibly sad,” wrote Colonel W. L. Goldsmith of Thomas’s Georgia brigade, “and to many the poor night-birds seemed to be piping the funeral notes of the Confederacy’s death.”

declares itself to mark

“the spot,” it actually marks only the vicinity. The spot itself is less than seventy

yards away along the old Mountain Road.

Well-written account. I just found another book I have to get – great job, guys!

Do you prefer orders through Amazon or a different site?

Sarah,

Thank you for the kind words. Any site you purchase one of our books from is fine with us. Amazon or the Savas Beatie website are the first places that we normally tell folks to start. We also sell books at all of the presentations we give.

Excellent. Thanks!

My gr-grandfather was a member of the 18th NC and this description helps makes that night come to life for me.

I have family members who were soldiers in the 18th ad 33rd NC at Chancellorsville…. an uncle claims to have helped carry Gen. Jackson off the battlefield. This uncle was later interviewed in a newspaper and claimed to have also accompanied Jackson’s body to VMI in Staunton, and then on to Lexington, Virginia for the burial. Does anyone today know the names of any of the soldiers who accompanied Jackson off the battlefield and through to the burial?