A Matter of Tactics revisited: 1815 vs. 1863 (Part two of a series)

On June 18, Europe celebrated the 200th anniversary of Waterloo, one of the most decisive engagements in history. 5,000 reenactors recreated the event, and it garnered a great deal of attention on the web. On July 1-3, here in the United States, we marked the 152nd anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg – not nearly so decisive, perhaps, since it did not end two decades of war in a single afternoon, but equally famous.

On June 18, Europe celebrated the 200th anniversary of Waterloo, one of the most decisive engagements in history. 5,000 reenactors recreated the event, and it garnered a great deal of attention on the web. On July 1-3, here in the United States, we marked the 152nd anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg – not nearly so decisive, perhaps, since it did not end two decades of war in a single afternoon, but equally famous.

Reflecting on the two battles, both of which fascinate me, I am struck by how often it is mentioned (usually in passing) that the two epochs shared essentially the same tactics – and how much those tactics were outdated by the time, on that sweltering Pennsylvania afternoon of July 3rd, roughly 12,000 Confederates stepped off for their assault against Meade’s center.

Is this really an accurate observation?

Certainly there is a great deal of truth in it. But there are considerable differences between the two periods, as well.

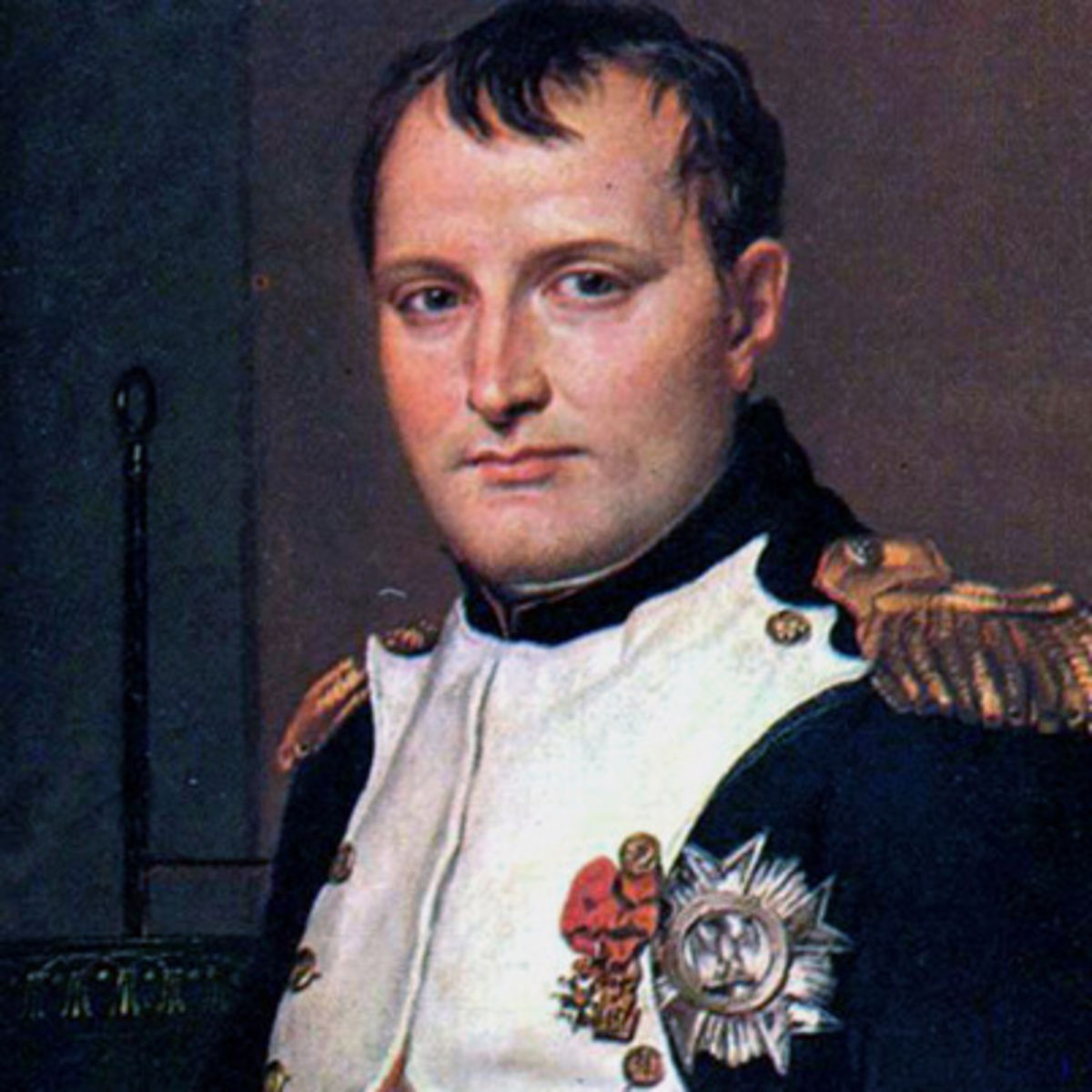

Of course the American Civil War owes a vast military legacy to the wars of Napoleon. How could it not? The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars lasted from 1792, when Europe’s royalty moved to crush the French mob, until the Emperor’s final abdication in 1815. The era encompassed twenty-three years of nearly constant warfare, witnessing more than 100 battles of at least 50,000 combatants. Even a century later, on the eve of a much greater conflict, professional soldiers would assiduously study Napoleon’s art of war, as Europe once again convulsed in continent-wide combat.

Of course the American Civil War owes a vast military legacy to the wars of Napoleon. How could it not? The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars lasted from 1792, when Europe’s royalty moved to crush the French mob, until the Emperor’s final abdication in 1815. The era encompassed twenty-three years of nearly constant warfare, witnessing more than 100 battles of at least 50,000 combatants. Even a century later, on the eve of a much greater conflict, professional soldiers would assiduously study Napoleon’s art of war, as Europe once again convulsed in continent-wide combat.

We can divide the Napoleonic era’s influence, however, into two realms; grand and minor tactics, with the first much more influential than the other. Grand tactics – what theorists today call the operational level of war – is by the most unembroidered definition, the art of maneuvering armies to the battlefield. It’s core doctrine can be succinctly stated as “march divided, fight united.”

That deceptively simple catch-phrase hides a host of complexities. Essentially, however, it means that armies which spread out to use multiple roads can move more swiftly than armies who attempt to jam their entire force onto a single avenue of approach. This became important because the Napoleonic era also gave us the concept of the nation in arms; the famous Levee en Masse used by the French to field enormous armies of a size never before seen in Europe. An army of 100,000 or 150,000 men needed much more space and flexibility than a force of 40,000.

The art of grand tactics was in bringing divided columns together at just the right time and place to fall upon one’s foe, ideally before that foe has managed to similarly unite his own divided columns. Even the creation of the idea of the army corps – that force of all arms capable of holding its own for a limited time – owes everything to this concept. A corps could buy time for the army commander to unite the rest of his force when the moment of battle arrived. The carry-through is obvious to any student of Civil War military affairs. We see these concepts being employed in any number of Civil War campaigns. Napoleon’s legacy is unmistakable here.

But what of minor tactics? Did the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble assault fail because the regimental, brigade, and divisional commanders were employing outdated formations?

In fact, minor tactics evolved significantly during the forty-six year gap between when L’Armee du Nord watched in dismay and disbelief as “Le Garde Recule!” and the firing on Fort Sumter. The primary reason for this, of course, was that weapons changed a great deal.

In a previous post, I referenced some of this, but only in passing. Now seems like a good chance to explore those changes in a little more detail.

Effective range for the smoothbore-toting troops of Napoleon’s era was 100 yards. 150 yards (or the metric equivalent) was considered extreme. Infantry that opened fire at that range were usually considered poorly trained, of uncertain discipline and morale, or all of the above. The better infantry reserved their fire until the target was even closer; 75 yards or so.

One ongoing debate within the Civil War community has concerned the effect of the rifled musket. For many years, the conventional wisdom held that the advent of the rifled musket made the defense much more effective, since a defender could now engage an attacker an ranges unheard-of with smoothbores; the British-manufactured 1853 Enfield was sited to 800 yards, and our own Springfield had a simpler iron sight that was meant for ranges of up to 500 yards.

That conventional wisdom has largely been upended by a cadre of scholarship arguing (rightly) that it took a great deal of skill and specialized training to actually use rifled muskets at extended range, skills and training that, until late in the war, most Civil War infantry never received. Even in 1864 such instruction tended to be cursory; a few rounds fired at pre-set targets, and a few afternoons of range estimation practice on a course of measured distances. Thus, without intensive training, actual engagement ranges were actually much less than those theoretical maximums: 200 yards, or perhaps 300, terrain and vegetation permitting.

Even if we accept the new school of thought whole-heartedly, it should not be overlooked that the engagement range of a typical Civil War musketry duel was roughly double that of its Napoleonic counterpart.

The full scope of that still-unresolved debate is far beyond what can be explored here. It is worth noting that most of the writers embracing the tactical revisionist school of thought tend to dismiss this doubling of range as either inconsequential, or of marginal impact. I think that overstates the case. Given that rates of fire remained virtually unchanged between smoothbore flintlocks and percussion muzzle-loading rifles, a doubling of the beaten zone, (that area of the approach swept by enemy fire, also sometimes dubbed the deadly ground) meant doubling the amount of effective fire that could be delivered against an approaching target. Given that combat between infantry formations was as often as not a contest of morale as it was of musketry, the strain on an attacker approaching a determined defender was much more significant.

It is also worth noting the improvements in artillery, which sometimes seems to get overlooked. Napoleon, who was a gunner first before he became the conqueror of Europe, lavished a great deal of attention on his artillery train. His armies marched with a large complement of cannon. At Waterloo, Napoleon fielded 75,000 effectives, accompanied by 254 cannon. However, only 42 of those were heavy guns, the famous 12-pounders that Napoleon so favored. 142 other pieces were 6-pounders, and the remainder were short-barreled 5 1/2 or 6 inch howitzers (much different than a civil war howitzer – see below.)  Wellington, commanding the Anglo-Allied army, also brought about 75,000 men to the field, but his force included only 157 guns, and none of those were 12-pounders. His ordnance included 60 9-pounders, 67 6-pounders, 30 5 1/2 inch howitzers, and a rocket section.

Wellington, commanding the Anglo-Allied army, also brought about 75,000 men to the field, but his force included only 157 guns, and none of those were 12-pounders. His ordnance included 60 9-pounders, 67 6-pounders, 30 5 1/2 inch howitzers, and a rocket section.

Weight was a factor in both the size and number of guns fielded. The British 12-pound gun in use at the time weighed in at 3,150 pounds; with limber, 6,500 pounds – which explains why they were reserved mostly for garrison use. Napoleon’s 12-pounders, by contrast, had a combined weight of 4,367 pounds, a distinct advantage over British guns, but still ponderous by Civil War standards. Hence the prevalence of so many lighter pieces.

At Gettysburg, Meade’s army brought 372 guns onto the field, while Lee made do with 280. On each side, just about half of these were the excellent 1857 12-pound gun-howitzer we all know of as the Napoleon (named not after the Emperor, but instead his nephew, Napoleon III, who sat on the French throne at the time.) The bulk of the others were 3-inch ordnance rifle, the 12-pound howitzer (Model 1841, not the Napoleon of the same weight) and an assortment of other, more rare pieces. A Napoleon gun and limber combination weighed 3,865 pounds, while the 3-Inch rifle combination weighed just under 3,500 pounds. Each was considerably more nimble on a battlefield than their 1815 counterpart, and they fired much more effective ammunition to boot. In short, the mobility and killing power of artillery was greatly enhanced.

19th Century theoreticians were not unaware of the apparent defensive advantages conferred by these new weapons. How, then, could an attacker overcome them?

Their solution lay in speed. 18th century armies maneuvered very slowly. The emphasis was on keeping formation, and executing complicated movements like wheels and obliques (a line or column moving at an angle instead of straight ahead) was done slowly to avoid disruption. How slowly?

The average pace for an 18th century European army was 75 steps per minute, which amounts to just under 60 yards per minute. (Of course, each army had a somewhat different idea of how long an individual pace or step was, but usually, it amounted to something close to 28 modern inches.) This pace – “common” or “ordinary” time in the manuals – was exceedingly slow. By way of comparison, a modern funeral march moves along at 90 steps per minute.

By the Napoleonic era things sped up slightly, but only slightly. Here are the distances given in an 1807 British manual:

(Note: the yards per minute figure is my modern calculation, used for comparison purposes)

Ordinary step – 75 paces per min, 30 inch step. 62.5 yards per minute.

Quick step – 108 paces per min, 30 inch step. 90 yards per minute.

Wheeling or quickest time – 120 paces per min, 100 yards per minute.

The order to “step out” increases each stride to 33 inches, at any of the above speeds.

The manual also cautions that the “ordinary” pace be used at all times, even on the battlefield, unless absolutely necessary. The primary reason for this was to ensure orderly formations.

By 1855 things were different. Here are the paces as defined in Hardee’s manual, which in turn was taken directly from the most advanced European thinking of the time:

Common time: 90 paces per minute, 28 inch step. 70 yards per minute.

Quick time: 110 paces per minute, 28 inch step. 85.5 yards per minute

Double quick – 165 paces per minute, 33 inch step. 151.25 yards per minute.

The double-quick may be increased to 180 paces per minute, 33 inch step. 165 yards per minute. This pace allows a formation to cover 4000 yards in 25 minutes.

Hardee also instructed that “common-time was to be used only in training, and then only for the newest recruits. Once men mastered maneuvering common time, they were to only be drilled thereafter at the Quick or Double-Quick. By the 1850s, theoreticians were assuming that all final combat maneuvering would be done at the Double-Quick (or the European equivalent thereof.) In essence, the pace of an attacker was now expected to be two or three times that of a similar formation in 1815.

No wonder the West Point cadets – whom became Hardee’s guinea pigs when it came to implementing the new drill – nicknamed Hardee’s system “the Shanghai drill.”

The intent is clear. Even though range and lethality had increased the killing zone, increased attacker speed should mean that advancing infantry would move through that kill zone more quickly, thus offsetting any increased defender advantage.

Did it work? Sometimes.

Increased speed had one other cost – to order and discipline. Infantry formations at the regimental/battalion level actually changed considerably between the two eras, becoming more flexible and less dense, in order to compensate for the quicker movements. The details of those differences, however, will have to wait…

Another major difference between the Napoleonic Wars and the Civil War is that in the ACW cavalry was almost totally absent from the battlefield. A major element of Napoleonic infantry tactics was trying to avoid being cut to pieces by the cavalry. My guess as to why cavalry in the ACW never really charged infantry is because the terrain very rarely permitted it. European battlefields were often rolling farmland with few obstacles for cavalry, American were often woody and crossed with ditches, creeks, ravines and fences that made cavalry far less useful.

Note that 4000 yards in 25 minutes is nearly a 10-minute mile. That’s essentially running: how would formations be sustained at that pace? Were the majority of volunteer units conditioned to move at this pace, which was derived from the French chausseurs?

Sam, Note that this last pace was only to be used in the final approach – a few hundred yards. I do have accounts of formations moving at the double-quick for a mile or more, and in theory they were all supposed to be drilled to this standard. Franz Sigel, for example, drilled his men for a week at Winchester to get them in shape in May, 1864; drill that consisted of at least 3 hours a day, sometimes twice that. Mornings were battalion (regimental) drill, afternoons were brigade drill.

What I don’t see any sign of in the sources is anything like what we would regard as a conditioning run, etc. The French would start placing a great emphasis on conditioning in the 1870s, but I don’t have any ACW evidence of this. Of course, a veteran unit was often already subject to plenty of conditioning just from marching.:)

Soldiers should be able to travel 40 miles in a day once every week. That could be jogging for 8 hours, walking for 16 hours, or a mixture of walking and jogging.

Walking = 2 mph to 4 mph

Jogging = 5 mph to 7 mph

Running = 8 mph to 10 mph

Sprinting = 11 mph to 45 mph (for a few seconds)

quick time = 3 mph = 20 minute mile

double time = 6 mph = 10 minute mile

triple time = 9 mph = 6 minute 40 second mile

A healthy teenager should be able to complete 15 minute mile once per day.

A healthy adult should be able to complete 10 minute mile once per day.

Soldiers are divided into three classes by “Sun Tzu’s Art of War”–1st class, vanguard, complete 60 miles per day; 2nd class, main-guard, complete 40 miles per day; and 3rd class, rearguard, complete 20 miles per day.

In ancient wars, only tooth are counted towards the number of combatant and government expenses; the tail are all considered camp followers, especially the surgeons. The conversion of camp followers, specifically staff officer positions, to military ranks is the classical era and the transition from bronze-age to iron-age.

Thanks, Dave. And I see you address the disorganization or dispersal at the end of your post. I wonder whether concerns for cohesion led most commanders to advance at a slower pace than the manual sought–to say nothing of terrain (whether woods or merely undulations or uneven ground). In other words, as with the rifle musket, we need someone to search the OR for the pace of attacks, to see if reality lived up to the manual. I have to confess, I read Earl Jess’s Civil War Infantry Tactics for LSU Press, and didn’t pay much attention to this question. 🙂

By the way, I love your games: I have all the CWBS, and the RSS. Love your Chickamauga book too.

Thanks, Sam.

Frankly, I was a bit disappointed with Hess’s tactics book. I thought it lacked detail in some important areas.

Civil War commanders tended to be more permissive regarding loose formations, but then, it seemed easier to get a formation back into tight formation in the ACW. I have noticed in Napoleonic fights that once a battalion was committed to fight in open order or deployed as skirmishers, they rarely reformed for close-order combat.

The year 1863 is when the Union changed the definition of regular regiment from 2 battalions to 3 battalions and added a headquarters company. The headquarters company is designed to be a bodyguard for the staff officers that finally develop at the regiment level. Staff duties originally were additional duties assigned to the officers of a regiment, but now, dedicated staff positions are created. To prevent rank inflation, officers must alternate between staff position and command positions before promotion.

S1 adjutant, personnel officer, administrative officer, etc.

S2 intelligence officer, etc.

S3 operations officer, operations and training officer, etc.

S4 logistics officer, commissary and quartermaster officer, etc.

S5 plannings officer, etc.

S6 signals and communications officer, etc.

S2 and S6 overlap in information technology.

S4 merges the commissary (food) and quartermaster (non-food) logistics.

S3 deals with operational level (pure strategy, military strategy, grand tactics), while S5 deal with strategic level (strategy polluted by politics, national strategy, grand strategy).

commander -> deputy commander -> chief of staff -> secretary of staff -> S3 -> S5 -> sergeant major -> captains by seniority

E9 = O5 in staff position and pay rate

E8 = O4 in staff position and pay rate

E7 = O3 in staff position and pay rate

E6 = O2 in staff position and O1 pay rate

E5 = Officer Cadet or Naval Ensign and pay rate

The sergeant major is originally an additional duty that all majors of a regiment must handle. Thus, the sergeant major is higher in the chain of commands than any captains.