“A Mosquito Fighting an Elephant”: A Carolinian’s Recollection of the Breakthrough

I found it challenging while writing Dawn of Victory to not slant my narrative too largely toward the Federals. This was largely the result of a paucity in material from the southern perspective. Many Confederate officers did not see the purpose in writing a report for the final days of the Petersburg campaign. No correspondence from those who survived the withering VI Corps assault could be sent from an army in full flight to the west. And for every voice that emerged after the war from the two Confederate divisions who covered the six mile stretch from Battery 45 to Hatcher’s Run, I had twenty letters or memoirs written by members of the Vermont Brigade alone.

I found it challenging while writing Dawn of Victory to not slant my narrative too largely toward the Federals. This was largely the result of a paucity in material from the southern perspective. Many Confederate officers did not see the purpose in writing a report for the final days of the Petersburg campaign. No correspondence from those who survived the withering VI Corps assault could be sent from an army in full flight to the west. And for every voice that emerged after the war from the two Confederate divisions who covered the six mile stretch from Battery 45 to Hatcher’s Run, I had twenty letters or memoirs written by members of the Vermont Brigade alone.

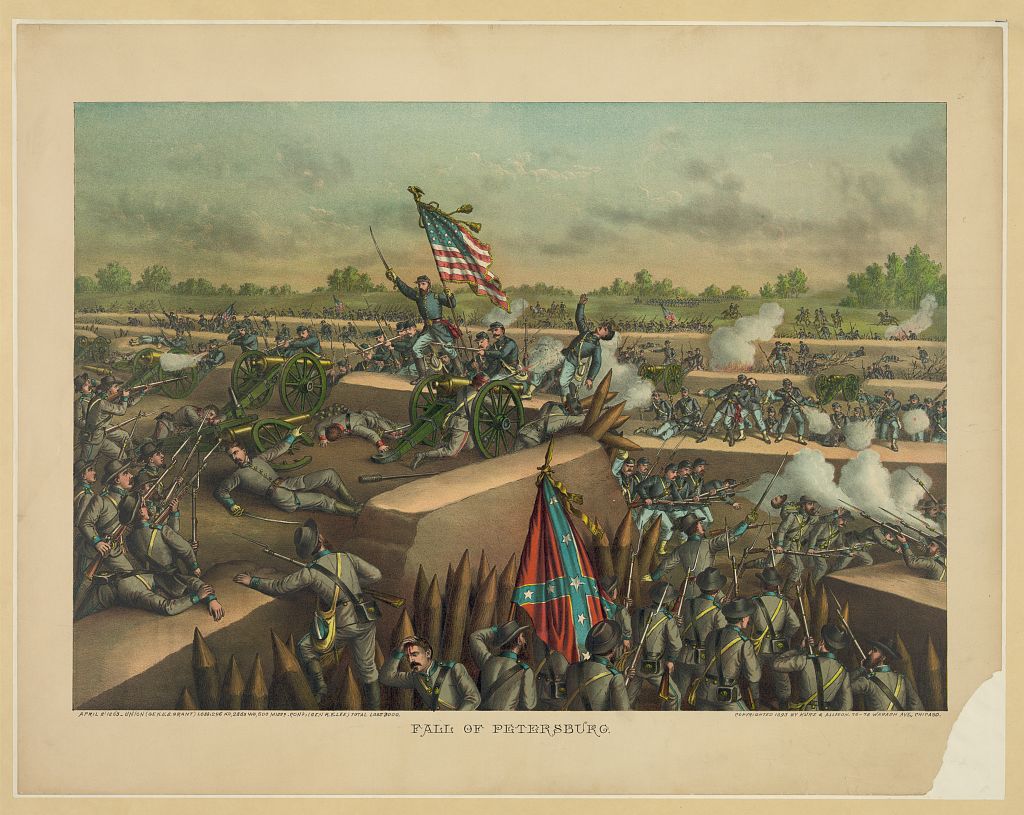

There are indeed a few moments from April 2, 1865 for the Confederates to hang their hats on–their stalwart defense of Forts Gregg and Mahone are covered in detail in the pages of Confederate Veteran and the Southern Historical Society Papers. The events that transpired along Arthur’s Swamp, however, did not inspire a desire to relive those moments via the pen. I traveled to Durham and Chapel Hill to find a few manuscripts from North Carolinians in the archives at Duke and UNC, but most of those resources came from the remnants of MacRae’s Brigade near Mrs. Hart’s house. It appeared that Lane’s much maligned brigade, stationed near Tudor Hall on the second day of April, simply did not want to share their experience. Just before my own manuscript was complete I took advantage of my subscription to the massive database at Newspapers.com to find a few articles from McGowan’s Brigade that appeared in the Anderson Intelligencer in the decades after the war. One vivid account, however, from a picket who protected Lane’s men seems to have eluded my keyword search and so I’d like to now present it below as a proper supplement to the story of the Breakthrough.

At the outbreak of the war, Patrick Henry Reilly lived in Charleston, South Carolina. Scarce information is available about his life before 1861. A search through genealogical websites finds a claim from his wife’s family that Patrick’s Irish immigrant parents died at an early age and that he was raised in an orphan home. His headstone gives him a date of birth of August 13, 1846, but his muster records show that he is eighteen in 1861. It’s a safe bet to assume that the youth fudged the details of his age to enlist.

On August 27, 1861, he mustered in to Captain C.D. Barksdale’s Company of the 1st Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers. This organization eventually became Company L, of McCreary’s 1st South Carolina (Provisional) Infantry. The regiment served in Maxcy Gregg’s Brigade, later commanded by Samuel McGowan. Reilly’s service records show that he was wounded at Second Manassas on August 29, 1862, and he received a promotion to corporal despite his absence while recovering. He returned in time to participate in the 1863 campaigns.

He was wounded once more during the 1864 Overland Campaign, likely on May 12th at the Bloody Angle. Once more he returned to his regiment from the Richmond hospitals with a promotion, this time to sergeant. Reilly found the 1st South Carolina Infantry stationed southwest of Petersburg on the Boisseau family’s plantation–Tudor Hall. On March 29, 1865, Reilly was out on the picket line and thus did not join the movement as McGowan’s Brigade marched south to deploy along the White Oak Road. I’m selfishly glad that Reilly was left behind, as his memoirs provide a valuable voice for the fighting that took place at today’s Pamplin Historical Park.

“For months we have been reading war papers from a ‘General’ standpoint,” Reilly complained at the start of his article. He wanted the common soldier’s experience to be told of “the late unpleasantness.” Reilly’s recollections, though a valuable find in a desert of Confederate resources, do suffer from a few issues. Like many memoirs, Reilly finds a way to insert himself into the point of action at every opportunity during the final days at the war. As can also be expected, his article smacks of the “Lost Cause” perspective. Reilly laments how “yielding to overwhelming numbers and resources, we were compelled to lay our guns upon the stack at Appomattox C.H.”

The process of getting to Appomattox from Tudor Hall is, however, an enriching read to understand the Breakthrough from the Confederate perspective. His narrative jumps right into the rifle pits on the evening of April 1, 1865:

“During our last night as picket guard it seemed ominously still, and we heard, or imagined we heard, smothered orders and an occasional rattle of canteens, and we became impressed with the idea that the enemy meant mischief and were massing troops in our immediate front, and knowing that the trenches behind us were occupied only by a regiment of North Carolina troops deployed as skirmishers, and the only reinforcement they could hope for was from such as were driven in from the picket line when the assault was made, the prospect was not encouraging.”

Brigadier General James H. Lane’s four North Carolina regiments covered the one mile stretch from the middle branch of Arthur’s Swamp to Rohoic Creek. Before McGowan’s transfer to the White Oak Road line, both brigades shared this assignment. Lane’s officers complained afterward that their men were spread six to ten paces apart. Six Federal brigades of the VI Corps formed to assault Lane’s position. Another two brigades would attack below Arthur’s Swamp, where two of Brig. Gen. William MacRae’s North Carolina regiments guarded the line near Mrs. Hart’s house.

“We were in the position of a mosquito fighting an elephant,” Reilly recalled.

“We had in our squad a fine chorus, and, as whistling would not keep our courage up, it was proposed to have a sing, and one of the boys called out: ‘Oh! Billy, give us a song.’ The reply came quickly: ‘No, Johnnie, you give us one first.'”

Any opportunity to muffle the tramp of 14,000 pairs of feet into position for the assault would have been appreciate by the Federal pickets. The South Carolinians obliged them with a rousing rendition of “Farewell to the Star Spangled Banner.” Sergeant Reilly resumes his (perhaps apocryphal) narrative.

“The song was finished and we called out for the reply, as usual in our past winter chats. It was excessively dark, and we felt uneasy and uncomfortable. We felt that our singing could not keep them back until daylight, which we were vainly hoping for. Finally an answer came from the other side: ‘Hold on, Johnnie, we’ll give you a song directly;’ and in a minute we were greeted by a thundering chorus of firearms, with a minnie ball accompaniment, and the cry of ‘Charge!’ ‘Twas what we were expecting, and when the fusilade was delivered our guns were half loaded.”

I had always assumed, and still do, that the early hour of the assault favored the VI Corps. Reilly’s recollection does not convince me otherwise, the mountains of evidence from Federals to the contrary keeps the scales tipped in their direction. I am nevertheless intrigued by his opinion about nighttime combat.

“There is not much difference between a day fight and a night attack in a general engagement from a private’s standpoint. In either case he sees but little. What with the smoke, the dust and general confusion of a daylight engagement, the private sees nothing but in his immediate vicinity. But this night’s fight was something terrible, and ’twas well for us it was night, as this mighty host that was hurled against us would have swept us instantly from before them. We could hear a perfect babel of voices, while all was silent on our side–the men stood in grim expectancy. Then followed the popping of our skirmishers as they slowly fell back upon the main line of works. Just in our front was a morass, which impeded the enemy’s advance on us, and we stood at our posts until the works on our right were almost in possession of the enemy, and our little band beat a hasty retreat and made double-quick time to the trenches.”

From Reilly’s description it appears that he was on the left side of the line where a branch of Rohoic Creek could have delayed the Federal advance. His retreat to the main line would have placed him among Colonel Robert Van Buren Cowan’s 33rd North Carolina Infantry or Lieutenant Colonel John W. McGill’s 18th North Carolina Infantry, who had previous misfortune of their own with friendly fire.

“Upon reaching the breastworks we turned and fired in the direction of the advancing column, when the colonel commanding gave the order, ‘Cease firing!’ thinking that all our men were not in the works. I knew they were–at least all who were coming in–and, as soon as I could load my piece, I fired again, and the whole line opened. The now exasperated officer came forward and asked my name, company and regiment, which I knew meant court-martial. I asked him before he made the record to cast his eye down the right of the line, and we both saw a sight not often seen in war, romances to the contrary, notwithstanding. The enemy had already mounted the works. They could not be seen, but the flashes of the guns of the contending forces formed crosses, so close were the combatants to each other. It was a hard stubborn fight; neither party seemed inclined to yield an inch. Although overpowered, our boys stood the racket like veterans, as they were. It is all very well to talk of clubbing guns and bayonet thrusts, but few places in the late war have the same record as this part of the lines around Petersburg. This was as nigh to hand-to-hand fighting as we generally got. Our handful of men were contending with swarms, as the daylight afterwards showed.”

With their position flanked on the right, those of Lane’s Brigade who could manage to extricate themselves from the line began to retreat toward Battery 45 of the Dimmock Line–Petersburg’s inner defenses. “Being without an officer I voted myself commissary, and knowing that the stores would soon be in the hands of the enemy I went and drew as many day’s rations as I could conveniently carry.” Reilly’s prophecy about the fate of the Confederate winter huts was soon fulfilled. “In fifteen or twenty minutes the enemy were in possession of building and contents.”

As his men rounded up prisoners, pilfered the camps and struck in small squads for the South Side Railroad, Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright instructed seven of his eight brigade commanders to swing their regiments perpendicular to the Confederate earthworks and sweep down to Hatcher’s Run. They quickly crushed what resistance three of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s brigades could offer. The detour to the south did, however, buy time for Brig. Gen. Nathaniel H. Harris’s four Mississippi regiments to scrape together a defense at Forts Gregg and Whitworth.

“I now followed the scattered bands of men and we wended our weary way towards Petersburg, when a staff officer rode up and said we must rendezvous at Battery Fourty-five,” Reilly recalled. “In doing so it was necessary to pass the Half-Moon Fort [Gregg], and while doing so I saw men crowding into it. I asked to be allowed to enter, but was denied. I afterwards found out that it was a Forlorn Hope… Over the entrance might well have been written, ‘Who enters here leaves hope behind.'”

Reilly claims that at this time “an officer on horseback was seen to charge down upon the enemy’s picket lines, pistol in hand, and as he rode by the men he discharged his weapon in their very faces, until finally he was unhorsed himself, and it was passed from lip to lip ‘that’s A.P. Hill.’ Whether it was the General or not I cannot say, but that an officer boldly rode to his death when he found his cause lost, that I saw from my point of observation.”

All evidence from both Union and Confederate sources suggests that Reilly, like most memoirists, wanted to involve himself in events he was nearby but not a direct participant. Hill’s route never took him near Reilly’s position and the 2.5 miles from Battery 45 to where the Third Corps commander was killed is proof that Reilly did not witness the general’s fate. He would, however, have a front-row seat for the vicious combat that broke out less than a mile away at Fort Gregg. Having begun their morning opposite the Confederate works along Hatcher’s Run, Brig. Gen. Robert S. Foster’s division of the XXIV Corps now prepared to storm Gregg’s parapet.

“The first line for the charge on the Fort was formed and slowly advanced to a sunken road through the field where they stopped for a few moments, then with a cheer on they rushed but were met by a deadly fire; they were staggered and scattered, the colors went down and were picked up to fall again and again, and with heads down as though battling a hail storm, they at last reached the moat around the Fort and jumped in, and here they were unexposed to the scathing fire. Another line followed and yet another to share the same fate as the first. The ground in front of the Fort was literally black with dead and dying. From the sunken road I saw another and last line emerge, and they were met by a galling fire from the Fort.”

Two of Brig. Gen. John W. Turner’s brigades now lent their weight to the assault.

“They stopped like men dazed and staggered back to the road. Then by a desperate sally they too reached the moat which by this time was packed with men, and they commenced the process of scaling the embankment upon each other’s shoulders, and soon a dark half-moon of men were seen firing down upon the devoted few who were in this detached fortification.”

“They stopped like men dazed and staggered back to the road. Then by a desperate sally they too reached the moat which by this time was packed with men, and they commenced the process of scaling the embankment upon each other’s shoulders, and soon a dark half-moon of men were seen firing down upon the devoted few who were in this detached fortification.”

As this final blue wave crested the parapet, Private Lawrence Berry of the Washington Artillery seized hold of a lanyard. The Federals called for Berry to drop it or they would shoot him. “Shoot and be damned!” the Confederate replied as he yanked the string. Those who survived the burst were not as keen on providing the remaining Confederates an opportunity to surrender. Only the remonstrations of their officers prevented an outright massacre.

“Long and continuous was the fusilade, and I felt that not a man would issue from the fortress alive,” Reilly claimed. “I saw many of the assailants fall back into the moat which told too plainly that ‘last ditch men’ composed that garrison. After the firing ceased, not more than twenty unharmed men came out… The carnage in this short, sharp fight was terrible, and gave the advancing hosts of Grant a check, and allowed us time for our retreat which terminated at Appomattox Court House.”

1st Sergt. P.H. Riley, Co. L, 1st South Carolina Regiment appears in the parole list for the Army of Northern Virginia. Only six others from his company made it to Appomattox.

The veteran returned to South Carolina after the war where he married Lucy Lillias Goldsmith on October 20, 1874. The 1880 census shows the couple living in Greenville, South Carolina, with Patrick working as a warehouseman and Lucy keeping house for ten boarders with the assistance of a black cook and nurse. Lucy died in 1882 and Patrick followed in 1889. They are buried together in Greenville’s Springwood Cemetery.

Reilly’s memoirs were originally published in the Charleston Weekly News. I found them reprinted on October 5, 1882 as “Petersburg to Appomattox: The Experience of ‘a High Private in the Rear Rank.’ in the Anderson Intelligencer.

This is so great. My great grandfather was in Co K, 18th NC, Lane’s Brigade. He was seen at Petersburg in March 1865 as mentioned in J W Council’s Diary and is on the Appomattox Surrender Roll. If seems he did not fight at Fort Gregg with some of Lane’s Brigade. I am thrilled to read about the days of the breakthrough from a Confederate. Thank you so much for posting.

Excellent post! I love to see new primary source material surface. Especially, as you say, one so rare. Cheers!

Thanks! Your scholarship, diligent research skills and writing style delivered the goods!

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.

Very good!

Reblogged this on Poore Boys In Gray and commented:

More on the fighting at Fort Gregg, where William B. Poore made a last stand at the Alamo of the Confederacy…