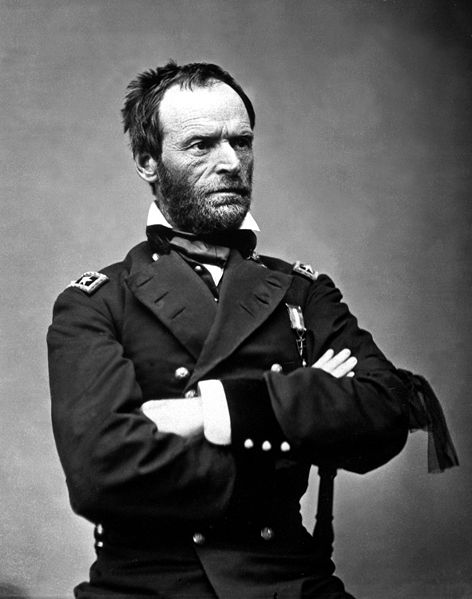

Mediocre to Average? William T. Sherman as a Battlefield Commander

The subject of the post is a question that has been puzzling me for quite awhile. Indeed, one could consider this a Question of the Week, but on steroids. Was William T. Sherman, a man who remains in the pantheon of the great Union commanders, just an average combat officer? For certain, Sherman never really did anything spectacular. In fact, his combat record prior to becoming head of the Military Division of the Mississippi is unspectacular to say the least. Unfortunately, a summary examination leaves us with more questions than answers.

Sherman’s first meaningful assignment came as a brigade commander at First Manassas. His one battle in the east is often forgotten since the bulk of his service was in the Western Theater. Transferred to Kentucky, Sherman eventually was placed in command of the Department of the Cumberland, but was relieved on the grounds that he was incapable of holding such a high post. Northern newspapers even accused him of being “insane”.

Sherman bounced from one assignment to another before he finally took command of a division that eventually joined the Army of the Tennessee. He led this division at the Battle of Shiloh where, despite giving ground throughout the first day of the battle, fought stubbornly. His next chance to lead men in battle came late in 1862 during an expedition against Vicksburg. Facing Confederate forces north of the city, Sherman launched a series of unsuccessful frontal assaults at Chickasaw Bayou which resulted in a devastating repulse.

Sherman commanded a corps during U.S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign and in the fall of 1863 he was among the reinforcements dispatched to Chattanooga. Once again, Sherman did not perform well. Apparently, he did not learn from his experience at Chickasaw Bayou and during the Union offensive on Missionary Ridge, he once again resorted to head long frontal attacks which were turned back by Rebel infantry.

What makes things even more confusing is Sherman’s performance in 1864 and 1865. His problems were not as pervasive as they were when he was responsible for directing multiple armies. While the Atlanta Campaign and the Carolinas Campaign were not perfect by any stretch of the imagination, it does seem that Sherman had come into his own. He certainly had a mind that was more in tune with the looking at the overall, larger strategic picture. Sherman was also extremely skilled in the field of logistics, which contributed to the success of his later campaigns.

Interestingly enough, Sherman performed at his best when he was allowed to engage in massive and rapid maneuver. Maybe that was where his true strength lay. In February 1863, he led an expedition across the interior of Mississippi in an effort to break up the enemy rail network in the town of Meridian. Sherman was so happy with the outcome that it served as the blue print for his “March to the Sea.” Still, it seems odd that he performed better at the higher levels of command, rather than having a gradual rise like many of his peers. While questions concerning Sherman’s performance will continue to persist, perhaps it is best left to the individual to decide. No matter what the answer might be, he emerged from the war as a member of the great pantheon of Union commanders.

“He emerged from the war as a member of the great pantheon of Union commanders.” Isn’t that the final answer? The consensus of history. Nobody is good at everything; one can always find faults. The successful person finds his strengths and uses them to best advantage. That was Sherman. Of course, he was blessed to have a good friend in Grant with influence and opportunity to support him, and Sherman returned the favor. Their strengths reinforced each other and helped offset their weaknesses, like Lee and Jackson.

I think the comment – “Still, it seems odd that he performed better at the higher levels of command, rather than having a gradual rise like many of his peers” – drives home the point about Sherman. So many generals got promoted too high up the chain, being an effective combat commander at the brigade or division level doesn’t necessarily make you fit to command an army. And, likewise, it seems during the war that it doesn’t take a brilliant tactical mind to be effective as an army commander.

The Union Army top leadership was lacking in quality generals which was why a’drunk’ and an ‘insane’ general stand out as stellar. Am I right? The South garnered the quality ‘generalship’ from their culture of military training, Scot military heritage, and VMI? To think the Rebel Army was ahead of the game in wins up until Gettysburg. That’s a true reflection of their combat commanders.

Oh, Kim! Your Confederate slip is showing! See reply by David Powell for a better analysis of military leadership. David Powell understands the subject better than you or I. His reply shows the intelligence needed to discuss the question put forth in this post. Maybe it is because he is a graduate of VMI and has published articles extensively.

War is a diverse business. Great tacticians are not automatically great higher echelon commanders. Senior leadership is about picking people, developing relationships, forging a team, understanding logistics, nerve, stubbornness, etc. as much as it is about demonstrated brilliance on a battlefield. In fact, I’d argue that for the most part, the world’s great tacticians do not rise to higher command, or if they do, they will fail as often as not – because they lack those other skills.

We might look at Napoleon’s Marshals, for instance – men who all proved themselves able tacticians, sometimes brilliant tacticians, but who largely failed at higher command. Of the 25 or so men who carried the Baton under Napoleon, only 2 or 3 really managed to be effective at independent command. Why? In part because Napoleon, who’s own brilliance made him the ultimate micro-manager, never developed those skills in his subordinates. He did not pick commanders with an eye towards independent command.

Sherman grasped most of these principles, and applied them well. While in 1864 his command wasn’t without command problems (what Civil War army was?) it was a well-functioning force, and if the best we can say is that he did not blunder in front of Atlanta, then, well, he’s already well ahead of most army commanders of the era, on either side.

Perhaps best of all, Sherman was Grant’s best subordinate. He understood what Grant wanted, and did his best to fulfill that mission. I can think of dozens of examples just in the ACW where subordinates lost sight of the mission, with unfortunate consequences.

Sherman earned his place.

I think his battlefield command record is, at best, spotty. I don’t blame him much for Chickasaw Bayou or Missionary Ridge, as he faced really difficult terrain in those cases (and, in the latter, an outstanding opposing commander). He did OK at Shiloh. Where I think he really dropped the ball was at Atlanta and Jonesboro and Savannah; in all three cases he let an opportunity get away.

Different commanders have different strengths and weaknesses. Sherman was best at planning and executing a campaign. He was not that good at fighting a battle.

At Shiloh he was credited with “saving the day” by his leadership in battle. During the advance on Corinth in May of 1862 he directed men in combat twice — at Russell’s House (May 17) and at the ‘double log house’ (May 27), both times driving the enemy from their position. His performance here was viewed favorably. So in his brief time in division-level command, his combat record looks quite good.

His corps-level records was more mixed but I think the conventional wisdom that he did not perform well at Chattanooga is wrong. He attacked the rebel position in front of him because those were his orders. His attacks were repulsed because the rebel position was strongly held. It happens, even to good commanders.

Overall, I think his performance at Shiloh is probably his best at the lower level. I have to wonder though how much his removal from command of the Department of the Cumblerand haunted him going forward. Some interpretations tend to evolve over time and I think it will continue to do so with Sherman.

I think it is interesting to think about Sherman in comparison to his Atlanta opponent John B. Hood. Hood was an excellent brigade and division commander, a hard-hitting and trusted tactician. However, he floundered at higher levels of command. I think Sherman is the opposite of Hood. He was not an outstanding brigade and division commander and he was alright corps commander. As others have mentioned, his value to Grant was that he would everything within his power to accomplish the tasks given to him by his commander. Sherman, however, did have a gift for logistics and for maneuver. These gifts served him well during the Atlanta and subsequent commander. While his battlefield record was, indeed, spotty at best, he was an excellent strategic level commander, whose success at that level minimized his tactical shortcomings.

Another point of view on Missionary Ridge would consider two additional facts. 1. Sherman was still suffering depression regarding his son’s death. 2. Probably in part for this reason he turned over command of the attack to his brother-in-law Gen. Ewing.

Perhaps Sherman can be faulted for not having a good map of the terrain and failure to correct for this when doing his night-time survey of the territory. He and Ewing mis-judged their position for beginning the attack. All this to say that the situation at the north end of missionary Ridge, Nov. 24 and 25, 1863, was complicated and requires considering many factors to reach conclusions as to “blame”.