Gone For A Soldier: Journeys of Irish American Music & Patriotism

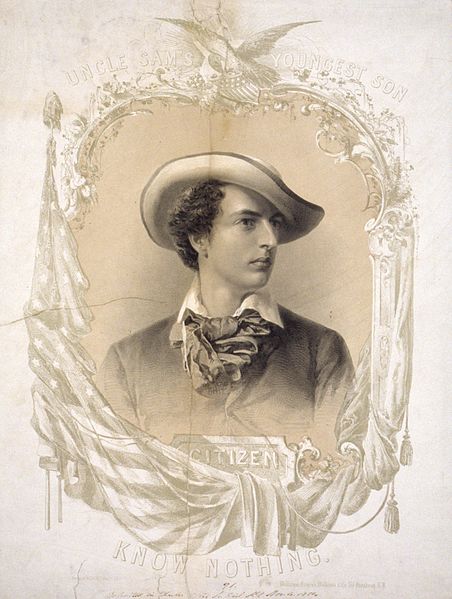

![Johnny Is Gone for a Soldier. (1862) Sep. Winner, Philadelphia. [Notated Music] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200001462.](http://emergingcivilwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/1652-e1458061232237.jpg?w=300)

The war-song Johnny Has Gone For A Soldier is a hallmark of folk music, and, though usually associated with the American War for Independence, it was also known and sung during the Civil War. The song is closely related the Irish song Shule Agra which is believed to have been created during the 1600’s. At some point in the next century, the English and Americans begged, borrowed, or stole the tune and foundational lyrics to create Johnny Has Gone For A Soldier. On both sides of the Atlantic, the lyrics were altered to suit the conflict, social standings, and situation, and the song eventually entered the anthology of American folk music with its exact origins elusively mysterious.

The Irish people were some of the earliest colonists. As the colonies expanded under British rule, a people group collectively known as the “Scots Irish” crossed the Atlantic, searching for land, safety, and religious freedom. They were mostly Protestants, and some had actually immigrated from Scotland to Ireland during the persecution of the Covenanter Presbyterians during the mid-17th Century. In America, these new settlers tended to establish their communities away from the seaboard, appreciating the fertile land for farming; eventually, they began the earliest westward expansions into the Valley of Virginia, the Appalachians, and the Ohio River Basin. Thus, the early Irish immigrants established themselves in the colonies and early Federalist America as small farm owners or tradesmen in village communities.[i]

By the mid-19th Century, new waves of immigrants from Ireland were arriving, fleeing famine, seeking new economic opportunities, or avoiding arrest for revolutionary ideas. America was entering the Industrial Age and – with expansion into the west and gold rushes tempting easterners to the open land – there were plenty of job opportunities. Irish immigrants arrived by the thousands and usually settled in or near the large industrial cities, primarily in the north.[ii]

Despite unfriendliness and challenges from society, most of the Irish people wanted to be good citizens and win acceptance. They worked hard, prospered, and banded together to encourage each other and remember the positive nostalgia of their green isle. Politicians began to court the Irish vote, realizing the formerly untapped power of the new citizens.

While the Irish Americans prospered, “native born” American society did not cordially welcome these newcomers. Suspicious of their Catholic religion, accents, cultural differences, and the desire to maintain their homeland heritage through clubs or leagues, many Americans turned a cold shoulder or were openly hostile to the new citizens. American nationalism, the “Know Nothing” political groups, and narrow-minded protestant preaching did not help the situation. With their thick accents and sometimes simple-minded wonder at industrialism, the Irish Americans became the butt of unkind jokes, cartoons, and songs which usually stemmed from and emphasized racial prejudice. Unknowingly, by choosing to use song to mock the immigrants, the prejudiced “native born” citizens opened a door for the Irish to welcome themselves.

The music from the Emerald Isle is a story and soul of its own. It can be lively, playful, and exuberant. It can also be melancholy, lost, and wailing. Rooted in the tumultuous history of the island, Irish music tells the best, worst, and most humorous of human nature. Best of all, the tunes and lyrics were transportable – learned and written in the hearts of the people.

Around the time when large numbers of Irish immigrants were coming to America in the early 19th Century, traveling performers, minstrel shows, and the forerunners of vaudeville were becoming popular. Though often crude and certainly lacking the political correctness of the 21st Century, these shows were well attended. The Irish were among the ethnic groups which became the jokes of the minstrel shows. Some Irish realized that the minstrel platform – even with all its unkindness and rough humor – was a way to share their culture and music. They joined theater troops and entertained with traditional Irish tunes and new songs with Irish flare between acts. Through these performances and other outlets, America was introduced to the fun, beauty, and uniqueness of Irish music.[iii]

Stephen Foster, arguably one of the best known songwriters in American history, was actually a descendant of Irish immigrants.[iv] His music – influenced heavily by tunes from the isle – combined Old World tradition of tunes and lyrics with the feelings of the New World to create completely American music. Foster’s songs were wildly popular during the 1850’s and 1860’s, and perhaps few prejudiced people realized just how much “Irish” was in the music they adored. Through the minstrel theaters and popular sheet music, they were opening the hearts of the people in their new homeland and the divisive conflict unleashed new music and new feelings for the American Irish.

The American Civil War brought a variety of ideas and motives to the Irish American communities in the north. Some men felt that enlisting and fighting for the Union would win them recognition and respect from other Americans. Others wanted to form regiments and see battles, in preparation for returning to liberate Ireland. Still others found common ground in the fight to end slavery, identifying with the emancipation movement because of their slave-like experiences in Ireland.[v] However, not all Irishmen were enthusiastic about the war; many resented the draft (sometimes violently) or aligned closely with the Copperheads.

The war produced an influx of new music, celebrating the deeds of Irish units and linking Ireland and America’s historic quests for freedom. Pat Murphy of the Irish Brigade included a plethora of Irish words as it told the tale of a young volunteer who passionately loves his new county and says “…I’ll fight till I die if I never get killed for America’s bright starry banner.” The lyrics go on, detailing the Irishmen in battle and the song comes to its tragic ending, “But he died far away from the friends that he loved, And far from the land of shillelagh.”[vi] This song – like others written during the Civil War – represents a shift in “native born” thinking about their Irish American neighbors; suddenly, the brave Irish volunteer is fighting and dying for his adopted county, far away from his ancient homeland – the Irish soldier becomes a hero and a patriot to America.

The music reflects the reports from the battlefields. While there were many Irish regiments and units which certainly deserve studies of their own, the famed Irish Brigade of the Army of the Potomac tends to steal the battlefield attention by their desperate valor. At the Sunken Road during the Battle of Antietam and the Plains of Marye’s Heights at the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Irish Brigade entered combat zones and returned fire while “native born” officers and men of other units watched. Respect and admiration for the Irishmen’s battlefield achievements helped to less some of the prejudices.

Reports from the battlefields emblazoned the headlines of newspapers. The casualty lists were searched with anxious eyes by those left at home. The young ladies in their fine parlors trembled as their fathers read out the lists of names while their Irish servant girls[vii] listened at the keyholes, desperate for news of brothers or sweethearts fighting for this new homeland.

While military music emphasized battlefield deeds and tragedies, the homefront searched for songs to adequately express loneliness and fear. Just as the Irish Brigade produced positive thoughts in the American military mind, traditional Irish laments touched the hearts of those left at home.

I’ll go up on Portland Hill

And there I’ll sit and cry my fill

And every tear should turn a mill

Johnny has gone for a soldier.

Shule, shule, shule agra

Sure, ah sure, and he loves me

When he comes back we’ll married be

Johnny has gone for a soldier.[viii]

It was the age-old tale. It was true in 17th Century Ireland, 18th Century Colonies, and 19th Century America. The traditional Irish song captured feelings in evolving lyrics and in a plaintive, simple melody. It croons the emotion of a girl or woman when her beloved has gone to war…gone for a soldier.

Amongst the great heritage songs of America are plenty of tunes directly from Ireland or with distinctive Irish flavor. From success in the colonial days through the tribulations of unkind prejudices and to welcoming acceptance in later times, the Irish have been part of the American story. And their music has often provided the words or tunes the country needed.

[i] (Essay) David Noel Doyle, “Scots Irish or Scotch-Irish” featured in Making The Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, edited by J.J. Lee and Marion R. Casey, (2006), pages 151-170.

[ii] (Essays) David Noel Doyle, “The Irish in North America, 1776-1845” and “The Remaking of Irish America, 1845-1880” featured in Making The Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, edited by J.J. Lee and Marion R. Casey, (2006), pages 171-252.

[iii] Irwin Silber, Songs of the Civil War, (1995), page 177.

[iv] J.J. Lee and Marion R. Casey, editors, Making The Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, (2006), page 218.

[v] Irwin Silber, Songs of the Civil War, (1995), pages 177-179.

[vi] Ibid., pages 219-221.

[vii] Many Irish girls and women took jobs as paid servants in northern households; it was considered a respectable position and became a way for women in Irish immigrant families to add to their family’s income while learning valuable details about American society. For more information see: (Essay) Margaret Lynch-Brennan, “Ubiquitous Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930” featured in Making The Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, edited by J.J. Lee and Marion R. Casey, (2006), pages 332-353.

[viii] There are many variations of the Irish/English/American lyrics for Shule Agra / Johnny Has Gone For A Soldier. I decided to use the variations presented on this website.

Shule Agra – http://www.contemplator.com/ireland/shulagra.html

Johnny Has Gone For A Soldier – http://www.contemplator.com/america/johngone.html

Reblogged this on seftonblog.

Thanks!