Promoting Grant

Before putting Ulysses S. Grant’s name forward for promotion to lieutenant general, Abraham Lincoln had to first find out whether Grant had any presidential ambitions—not an unreasonable concern in an army filled with politicians and political aspirants. With the presidential election coming later in the year, and with no end of the war in sight, Lincoln worried about his vulnerability. He didn’t need his winningest general as his political opponent.

Of course, Grant would hardly say so outright if he did, so Lincoln had to surreptitiously poke around. He found his surrogate in former U.S. Rep. Isaac N. Morris of Illinois. Morris was the son of the late U.S. Sen. Thomas Morris of Ohio and a friend of Grant’s father, Jesse. Morris wrote to Grant on December 29, 1863, to pose the question. Lost among the voluminous correspondence he received, Grant didn’t see the letter until January 18. “I receive many such letters,” Grant explained in his January 20 response, “but I do not answer. Yours however, is written in such a kindly spirit, and as you ask for an answer confidentially, I will not withhold it. . . .

I am not a politician, never was and hope to be, and could not write a political letter. My only desire is to serve the country in her present trials. To do this efficiently it is necessary to have the confidence of the Army and the people. I know no way to better to secure this end than by a faithful performance of my duties. . . . In your letter you say that I have it in my power to be the next President! This is the last thing in the world I desire. I would regard such a consummation as being highly unfortunate for myself if not for the country. Through Providence I have attained to more than I ever hoped, and with the position I now hold in the Regular Army, if allowed to retain it will be more than satisfied. I certainly shall never shape a sentiment, or the expression of a thought with the view of being a candidate for office. I scarcely know the inducement that could be held out to me to accept office, and unhesitatingly say that I infinitely prefer my present position to that of any civil office within the gift of the people.

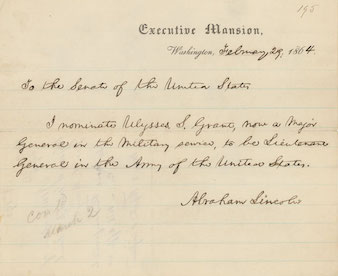

Grant asked Morris to keep the letter private and confidential. However, the answer did make its way back to Lincoln, and it was just what the president needed to hear. Congress moved on the legislation required to officially create the rank, which Lincoln signed into law on Leap Day, February 29, and sent Grant’s name forward for consideration that same day.

* * *

The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: January 1-May 31, 1864. Vol. 10. John Y. Simon, ed. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University press, 1982. Pg. 53.

Didn’t Lincoln also use Leonard Swett to sound out Grant on this? And perhaps someone else as well?

As I understand it, Lincoln used a few back channels. I don’t know a lot about the relationship between Grant and Swett except that it started out on the wrong foot, although Swett grew to have a grudging respect for Grant in spite of it.

What was required to complete Lincoln’s next step toward finalizing his war-winning team, appointing LTG Grant as Commanding General of the United States Army?

Once Lincoln realize he wouldn’t be promoting a potential political rival into the spotlight, he went ahead and got the gears rolling to recreate the rank of lieutenant general, something only Congress could do. When they did, it was obvious there was only one person being considered for the position.

Another beautiful piece of writing by Grant. The first sentence is a drum roll.

Mcatty:

Right you are. The battlefield orders of many Civil War generals often were vague and confusing. Grant’s never were. Sometimes his subordinates failed to follow Grant’s orders, but they could never claim they misunderstood them.

Grant’s memoirs, which he competed literally days before his death, were written the same way. By far, the best memoirs of any major Civil War general. Some skeptics speculate that Mark Twain ghosted Grant’s memoirs. Such skeptics obviously have never read Grant’s letters or battlefield communiques.

One of the things Grant discovered while writing the book was that he was, indeed, a writer after all. “[F]or the last twenty-four years I have been very much employed in writing,” he told former aide Adam Badeau during the last couple months of his life. “As a soldier I wrote my own orders, plans of battle, instructions and reports. They were not edited, nor was assistance rendered. As president, I wrote every official document, I believe, usual for presidents to write, bearing my name. All these have been published and widely circulated. The public has become accustomed to my style of writing. They know that it is not even an attempt to imitate either a literary or classical style; that it is just what it is and nothing else. If I succeed in telling my story so that others can see as I do what I attempt to show, I will be satisfied. The reader must also be satisfied, for he knows from the beginning what to expect.”

I’ve always found this quite interesting and this is one of my favourite letters of Grant’s. Great post!

Merci!

thank you very interesting side bar .guess he changed his mind after the war to bad for him.

His presidency didn’t turn out all that bad, although it wasn’t all that great, either.

Great letter! I love the second sentence.

Thanks!

Grant didn’t really change his mind about letting his name be brought up for president so much as he was very unhappy with the way the country was heading. With many former Confederate leaders being put back in office, with the unrelenting views of the radical Congress screaming for punishment of the South, with the growth of the KKK-kind of response to Reconstruction problems he was actually afraid another civil war would start . He felt he had no choice but let his name be put forth and said to Julia the night of the election “I’m afraid I’ve been elected.” Just like his foe, General Lee, he had a high sense of duty when appointed.