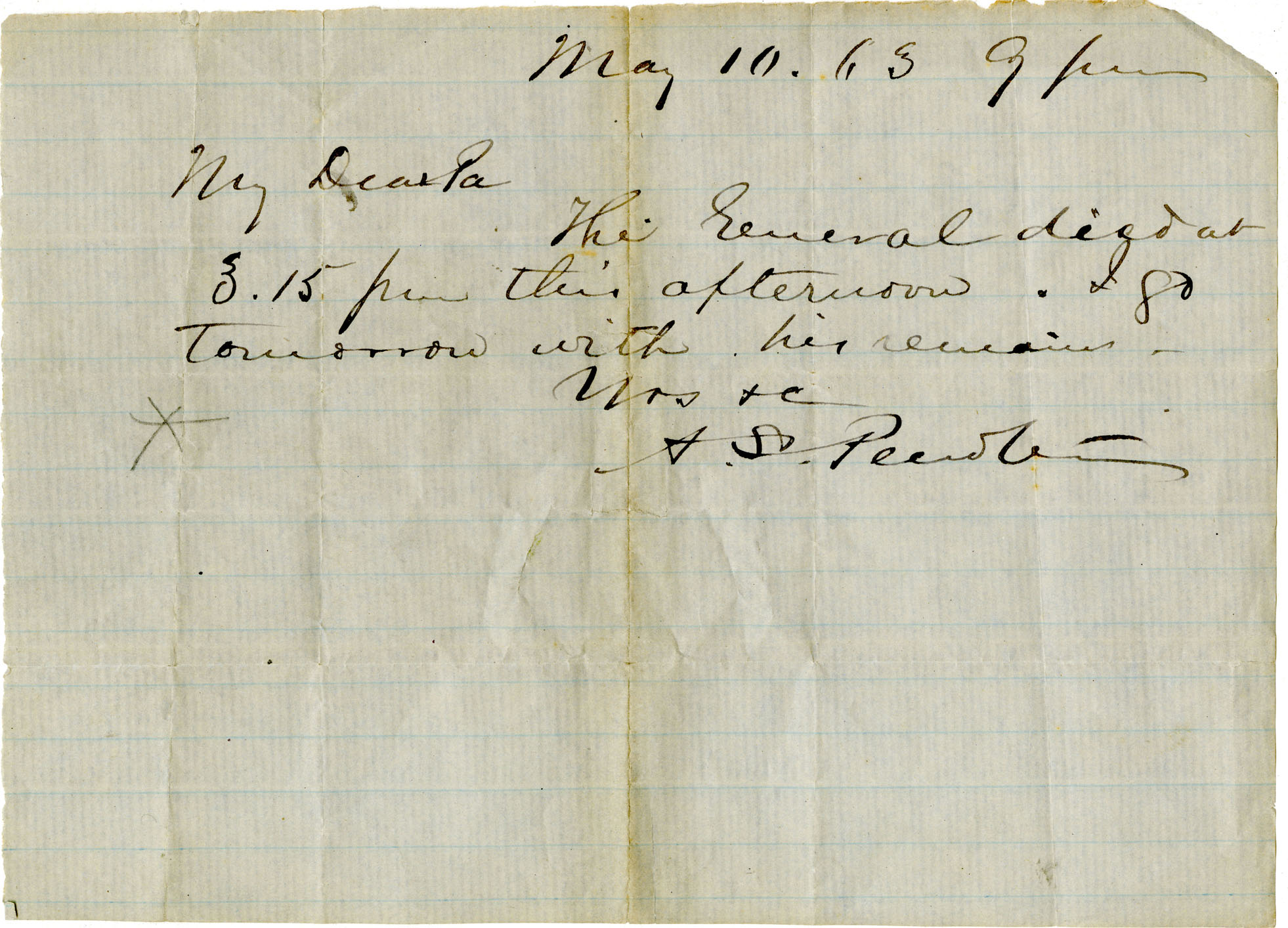

Written Words: “The General Died”

The casket was closed. Upstairs, Dr. McGuire and some of the other officers slept – or pretended to slumber. The candle flickered. He paced across the room and back, his boots echoing hollowly. General Lee knew. The Virginian governor knew. He had told them. The heart-stopping news would be sweeping through the army by now – whispers that would halt a man, forcing him to remove his hat with an anguished look.

The casket was closed. Upstairs, Dr. McGuire and some of the other officers slept – or pretended to slumber. The candle flickered. He paced across the room and back, his boots echoing hollowly. General Lee knew. The Virginian governor knew. He had told them. The heart-stopping news would be sweeping through the army by now – whispers that would halt a man, forcing him to remove his hat with an anguished look.

He momentarily regretted his position as assistant adjutant general. If he had only been an aide-de-camp like Smith or Morrison, he could’ve spent the last week with the general and wouldn’t have been ordered to take charge of all funeral arrangements. If only, he had not been forced to stay at headquarters all week. If only, they hadn’t glanced at him just moments after Jackson breathed his last and wordlessly nominated him to leave and tell the world. If only, if only, if only. Scenarios he believed he would’ve preferred tumbled in his mind, a useless distraction, trying to rationalize his feelings.

Alone. He felt so alone. Certainly he had his family, friends, and sweetheart, but tonight they were not at his side. He pulled his notebook from his pocket, then borrowed pen and ink from the makeshift desk. After writing the date, time, and salutation, he paused.

It was one thing to have announced it verbally – when the lowered voice, hesitation, or euphemism for death seemed to soften the awful truth. When he’d scrawled the message for the telegraph operator, he wasn’t really thinking; he had only being doing his duty, scribbling one of the hundred messages or notes he prepared in a day.

Now, though, alone with his thoughts, he faced the realities of what had happened. The tragedy and the new responsibility it forced on him. Just write the truth, he thought. Steadily, he formed the words. He signed it: A.S. Pendleton

A century and a half after Major Alexander Swift Pendleton wrote his brief, two-sentence letter to General William Nelson Pendleton, I found the digitalized copy in the on-line Virginia Military Institute Archives. That short note – written on the evening of May 10, 1863 – was a link to that historic day for me.

Major Pendleton – usually called by his familial nickname “Sandie” – has been on my “Civil War Hero List” for a long time. It’s hard to be unimpressed with his character and military leadership. After-all, in the 21st Century, the majority of twenty-two year olds are just finishing four years of college and looking for a job; they haven’t been overseeing an entire army corps for two years and directly contributing to a famous general’s military victories.

From First Manassas to Chancellorsville, Sandie Pendleton had been General Jackson’s right-hand man and served as acting chief of staff. On one occasion, Jackson replied to another officer’s request for information, “Ask Sandie Pendleton. If he does not know, no one does.”[i] Pendleton and Jackson also formed a close friendship, and some of the other staff officers believed Sandie was like the son Jackson never had.[ii]

Considering the close relationship between the general and his adjutant, Sandie’s absence during the friendly-fire on the turnpike and throughout the following week is conspicuous. Sandie Pendleton was with General Jackson on May 2, when the forward scouting trip began and advised his commander that they were not in a safe position. Moments later, Jackson sent Pendleton to take a message to General A.P. Hill.

It’s not quite clear if Pendleton heard about the general’s wound and galloped to find the medical director, Hunter McGuire, or if Pendleton, Jedidiah Hotchkiss, and Dr. McGuire were riding together in the dark wilderness when a messenger found them with the news. However Sandie received the news, his next action was swift. He had to find a commander to take command of the Second Corps. News arrived that General A.P. Hill was wounded, and the other senior commanders were tangled somewhere in the wilderness. Pendleton made the decision to send for the cavalry general, James E. B. Stuart to led the corps.[iii]

Hours later, General Stuart sent Pendleton to the field hospital to inquire about General Jackson’s battle plans. He arrived after the amputation of the general’s left arm and, after convincing Dr. McGuire that the army’s safety depending on the interview, Pendleton was allowed into Jackson’s tent. Explaining the current military situation, Pendleton waited for his commander’s orders, but the general’s response was startling feeble. “I don’t know – I can’t tell; say to General Stuart he must do what he thinks best.”[iv] Accustomed to Jackson dictating orders without hesitation, Pendleton quickly departed, breaking down in tears outside the tent. When Dr. McGuire joined him, Sandie admitted to his friend, “We didn’t know what he was worth, Mac, ‘til we lost him.”[v]

Sandie didn’t have time to contemplate the implications of the interview or his unknowingly-prophetic words. And he couldn’t stay at the field hospital. The Battle of Chancellorsville continued, and he helped General Stuart organize and led the Second Corps in the Confederate victory. Throughout the rest of the week, Sandie stayed at headquarters, hearing reports from Guinea Station, but unable to visit General Jackson.

On Sunday, May 10, 1863, while the army attended religious services, Sandie Pendleton rode to Guinea Station. He was unprepared for what he found. Entering General Jackson’s sick-room in the Chandler office building, Sandie saw his weakened commander feverish, semi-delirious, and struggling to breathe. Controlling his emotions, he approached the bed, reporting which chaplain was preaching at the Second Corps headquarters and mentioning that many soldiers were praying for his recovery. “Thank God – they are very kind,” Jackson murmured. He told his young officer, “It is the Lord’s Day; my wish is fulfilled. I have always desired to die on Sunday.”[vi] Pendleton retreated to hide his tears.

Two hours later, when General Jackson “cross[ed] the river” to “rest in the shade of the trees,” Sandie Pendleton was not given a mourner’s reprieve from military duties. For two years, he had been overseeing announcements, orders, and other numerous details for the Second Corps; he was the officer sent to tell the army that Jackson was gone. Riding north to the camps, Sandie informed General Lee, told his fellow staff-officers at the Second Corps headquarters, and galloped to the telegraph station to send the black-edged message to the Governor of Virginia. At some point during the afternoon, General Lee asked Sandie to oversee all funeral arrangements.

Returning to the small, white office building at Guinea Station, Sandie made the preliminary arrangements for transporting the general’s remains to Richmond. Sometime in the darkness, he wrote the note to his father. Did he write it matter-of-factly, simply as part of his duty to write messages? Did he scrawl it hastily and without much thought – too tired and sad to write more than two lines?

Clearly, Sandie’s note was unofficial, just a message from a son to his father; he did not sign his name with a military rank or title, and he uses the familiar salutation “My Dear Pa.” It is possible that General Pendleton already knew about General Jackson’s death, and he would undoubtedly hear from General Lee where his son was going. But there is something thought-provoking in the short note – a son’s need to speak. A young man’s need to write the blunt truth, perhaps as a way of beginning the acceptance and grieving process.

I stare at the digitalized image of Sandie’s note. Perhaps, someday, I’ll see the original paper; get to handle it gently while wearing gloves. But – for today – I can see it. I notice the original lined paper – possibly just a scrap or maybe a sheet removed from a pocket notebook. My eyes trace every letter, every word. This is history. It reports a historic fact. This is also personal. Perhaps I have probed too deep into a young man’s life and emotions.

I can’t know what Sandie Pendleton was thinking or feeling when he wrote this note. If I’m honest with myself, I don’t want to know that pain of losing a role model and best friend. However, while I chose to the close the door on my investigation, I consider some implications of General Jackson’s death and legacy.

I can’t know what Sandie Pendleton was thinking or feeling when he wrote this note. If I’m honest with myself, I don’t want to know that pain of losing a role model and best friend. However, while I chose to the close the door on my investigation, I consider some implications of General Jackson’s death and legacy.

As a battlefield commander, General Jackson had inspired soldiers and civilians. His victories gave them hope. His religious faith inspired them to greater devotion. His character was an example to his subordinates, peers, and military family. Though Jackson died, his memory and positive character qualities challenged all who had known him, Sandie Pendleton included. In November 1863 – six months after General Jackson’s death – Sandie wrote to his fiancée: “What a legacy of pleasure & pride for the days to come in the remembrance of long service to the entire satisfaction of such a man as he was, & the fact of having enjoyed his…confidence. One thing I know, I am a better soldier & a better man for having associated so long…with Gen’l Jackson.”[vii]

[i] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959) page 89.

[ii] Ibid, page 91.

[iii] Ibid, pages 115-117.

[iv] Hunter Mcguire, Article: Account of the Wounding and Death of Stonewall Jackson (first published in 1866.)

[v] Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White, The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson: The Mortal Wounding of the Confederacy’s Greatest Icon (2013), page 26.

[vi] Hunter Mcguire, Article: Account of the Wounding and Death of Stonewall Jackson (first published in 1866.)

[vii] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959) page 179, letter dated November 25, 1863.

Wow ! Your article really got to me. Well done, well done. Sarah Bierle

Brilliantly crafted, beautifully written, and with great compassion!

Fantastic post, all of your articles help us understand the people and events that you describe. This was very appropriate on the anniversary of Stonewall Jackson’s passing. I agree with the other commenters. It was great to hear about the relationship between Sandie and Jackson. Sarah, I just read your book: “Blue and Gray and Crimson”, also well done. I heartily recommend your book to everyone, it has something of interest for everybody and historically accurate.

That was a beautifully written article!

Well written article and it really got to me as well emotionally. Thank you for writing this. I need to get a copy of your book.

Thank you to all the readers who took the time to like this post or write comments. It is encouraging to me as a writer to know that my research and articles are meaningful. It gives me courage to keep searching for stories of historic courage in challenging or tragic situations. Thank you.

Excellent article! You perfectly captured the mood and spirit of that dark day, moving me to tears. You not only highlighted General Jackson’s exemplary character, but opened Sandie Pendleton to the awareness of a large group of people who have never heard of him. Thank you!