A Sharpshooter’s Postscript to Gettysburg, Part One: The Aftermath of Gettysburg

Part of a series.

Today we welcome Robert (Rob) Wilson, M.Ed., lives in Western Massachusetts and works as a part-time consultant for the National Park Service at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site in Springfield, MA. He recently retired from a 20 year career at the Veterans Education Project (VEP), a non-profit group that trains military veteran volunteers from WWII through to Afghanistan and Iraq to share their oral histories in Western Massachusetts schools. He was VEP’s Executive Director. Prior to VEP, he worked at different times as a teacher and a newspaper reporter.

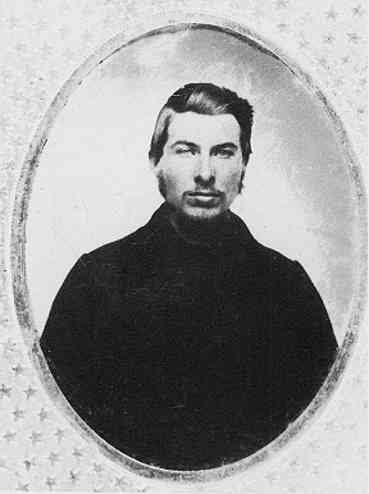

Currently Rob is in the process of reading, transcribing and writing about his great grandfather’s unpublished Civil War correspondence. His ancestor, George Augustus Marden, volunteered for the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters Regiment, served from late 1861 to late 1864 in the Army of the Potomac, and wrote home about seminal events of the war such as the Peninsula Campaign, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

The three days of major hostilities around Gettysburg ended on the July 3, 1863, with the bloody repulse of Pickett’s Charge on the Union center and two unrelated cavalry engagements. Each side registered what would stand as the longest casualty list of the war: The Army of the Potomac lost 28 percent of its force as dead, wounded or missing, while the Army of Northern Virginia suffered a 37 percent loss.[i] The Union had won the war of attrition, fought exceptionally well for the majority of the three days, and emerged from the dust and smoke of Gettysburg the victor. Yet fighting on patches of that iconic battlefield persisted on Independence Day, the day after the famous charge. As 24-year-old U.S. Sharpshooter and brigade Assistant Adjunct General (AAG) Lt. George Augustus Marden described it in a July 5 letter to his mother, he was on a break from an ongoing fight, not celebrating a victory. Sheltered in his tent from a downpour he wrote[ii]:

After three days hard fighting during which time our [Third] Corps has been constantly under fire, and our Brigade especially, I am safe and sound. A piece of shrapnel struck my stirrup yesterday [July 4] but it was so spent it did not penetrate but only gave me a slight bruise. Although our loss has been heavy, the wonder is so few have been killed… But I cannot stop to write more– the fighting is not over yet, apparently, but stop has been put to it by the rain.

Although soldiers of the Third Corps 1st and 2nd Regiments of United States Sharpshooters (U.S.S.S. or Sharps) had been among the units engaged on the Fourth of July as skirmishers and pickets, with 11 wounded and three killed, the July 5 combat Marden anticipated in Gettysburg never materialized.[iii] Having left nighttime campfires burning along Seminary Ridge to deceive its foe, the main body of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s battered Army of Northern Virginia stole away before dawn on the morning Marden sat writing his letter, beginning its retreat home. The planned escape route ran west over the Blue Ridge Mountains, south towards the Maryland town of Williamsport, then over the Potomac River into Virginia. [iv]

The Southerners would not travel alone. When a reconnaissance party of Marden’s Sharpshooter comrades confirmed the morning of July 5 that the main enemy force had withdrawn, Maj. General George G. Meade began to dispatch his army in pursuit, leading with 6th Corps. Over the next two days the remaining Army of the Potomac Corps were ordered to march south. Having been surprised in previous engagements by Lee’s bold tactics, the Federals stayed on roads to the east of the Confederate columns as they tracked their foe, ready to block any move towards Washington and/or Baltimore. Meade relied on his cavalry to harass and slow his enemy’s progress.[v]

The North had won what Marden called “the greatest battle,” yet the Gettysburg Campaign would continue with sporadic fighting for 18 days. This article and a series of related Emerging Civil War blog posts will focus on the time the two armies spent in Gettysburg after the battle and the 110 mile Union pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia. To examine this postscript to Gettysburg, the posts will draw heavily on the July letters home from the above-quoted George Marden, my great-grandfather. Other primary and secondary sources, citing both Union and Confederate soldiers, will fill out the story.

The events of Gettysburg’s postscript receive much less attention than the battle itself. No wonder: the fighting on Independence Day and the combat during the pursuit pale in comparison. More than 51,000 blue and gray soldiers were wounded, dead or missing after the three days of fighting, nearly one third of the men who marched or rode into battle.[vi] And the story of the pursuit is laden in controversy over General Meade’s leadership and “what ifs” about his strategic decision-making after the stunning victory in Pennsylvania. As the chase dragged on for nearly three weeks, with the Union force sometimes five miles or less from Lee’s lines, why were there no decisive attempts to attack? Could Meade’s force have finished off or dealt a crippling blow to the Army of Northern Virginia? There is much to examine in that direction, and writing about the pursuit easily drifts to that aspect of the story.

Yet the story of the battle’s postscript extends beyond battlefield statistics and questions about Meade’s post-Gettysburg generalship. Along with blood and sweat, there are moments of brilliance and ingenuity (mostly on the Southern side), bravery (by cavalry and infantry of both armies, as well as angry Pennsylvania civilians who attacked a train of retreating Confederate wagons with axes), the suffering of wounded Southern troops being evacuated on wagons, miscalculation, and lost opportunity. There is the story of Marden’s unit, the United States Sharpshooters— at Gettysburg and in the pursuit of Lee— that showcases who and what they were and the unique and important role they played in the Army of the Potomac. And thanks to the 47 pages of unpublished letters my ancestor mailed home over the month of July, there is new detail and insight into the story of the chase.

Lieutenant George A. Marden came from Mont Vernon, New Hampshire. The towns, population of just 700, had fewer residents than the number of soldiers in a standard U.S. Army regiment. The first in a large family of very modest means to go to college, Marden graduated in spring of 1861, and volunteered in November for duty in the Sharpshooters. Over the winter of 1861-62 he trained at the U.S.S.S. Camp of Instruction in Washington, D.C. with the 2nd Regiment, then transferred to the 1st for the spring and early summer Peninsula Campaign. After the Battle of Fredericksburg he was promoted to lieutenant and reassigned back to 2nd Regiment. He also was appointed as Assistant Adjunct General (AAG) for the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Division of III Corps (Called “Ward’s Brigade” after its commander, Brig. Commander John H. Hobart Ward: both 1st and 2nd Sharps served in that eight-regiment brigade). An AAG was a vital link in the brigade’s headquarters (HQ) communications and its chain of command. During marches and on the battlefield, he delivered HQ’s orders to his brigade’s regiments, visited and inspected outposts and lines to assure orders were executed, conducted reconnaissance and compiled and wrote operations reports.[vii] Because of Marden’s training and connections to the Sharpshooters, he occasionally was assigned a combat role, in his words “superintending” U.S.S.S. skirmish lines. His post as AAG provided him a panoramic view of division and brigade plans and actions, much more so than if he spent all his time with one regiment. He vividly translated his eclectic experiences—in camp, on the march and in battle–into his letters home.

![November 15, 1862 Harper's Weekly leaf entitled, "The Army of the Potomac – A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty [from a painting by Winslow.]](http://emergingcivilwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/the-sharpshooter.jpg?w=300)

A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty [from a painting by Winslow.]

The Sharps trained extensively as skirmishers, learning a variety of complex battle maneuvers and formations that multiplied their offensive and defensive capabilities. They often operated well in front of Union lines, acting as pickets and snipers as well as skirmishers. Some used rifles equipped with telescopic sites. The Sharps wore distinctive green uniforms that set them apart from their blue-jacketed comrades. The green served as camouflage in trees and underbrush. On an open battlefield, Sharps’ uniforms made them easy to identify and quickly assign where needed most. Their green clothes also marked them as priority targets for enemy riflemen, who viewed the marksmen, their weapons and their clever and effective tactics with measures of respect, fear and contempt. Some called the Sharps “snakes in the grass” and “green demons.” One Southern newspaper proclaimed that captured Sharpshooters should be hung as common murders.[viii]

On July 6, Third Corps was ordered to the south of Cemetery Ridge, in front of Little Round Top and the vicinity of Devil’s Den where Ward’s Brigade and other units had paid a high human cost on the second day of fighting to delay the Confederate advance long enough for reinforcements to arrive and prevent a total rout of the Union left flank.[ix]

Marden, who prior to the engagement had inspected his brigade’s positions near one of the farms standing in the way of the onslaught, wrote the area turned into “perfectly a little hell” during the battle. When the Corps was ordered to wait a day before marching south, New Hampshire Sharpshooter Wyman S. White, another 2nd Regiment Sharp who had fought on that left flank, visited some of the spots where he’d fought just four days before. As he described it in his Civil War memoir, Gray uniformed bodies still were strewn about in awkward positions where they had been killed, in some cases near the carcasses of dead horses.[x]

The next day, July 7, the Third Corps formed up and began their journey, leaving behind and the grisly surroundings and the stench of the battlefield dead. The rain cleared off by afternoon and the sub began shining. In contrast to his reflection on the battlefield visit the previous day, White’s description of passing through Fredericktown, Maryland, at sunset took on an almost ethereal tone. “[W]e were delighted with the beautiful scenery of the broad green fields dotted by fields of grain and orchards; fair as the garden of the Lord,” he wrote.[xi]

Not far down the road, however, a gruesome sight shattered that moment of peaceful beauty. The men passed “the body of a rebel spy, hanging to a tree,” White wrote. “I still remember how out of place a hanging body seemed in the midst of this beautiful landscape.”[xii] And so the soldiers marched on, reminded once again that this cruel war’s reality was not confined to the battlefield only: it could be waiting for them around the next bend or over the hill ahead.

Endnotes:

[i] Gettysburg Casualties, HistoryNet http://www.historynet.com/gettysburg-casualties Retrieved May 15, 2016

[ii] The Civil War letters of George Augustus Marden, July 11, 1863. Courtesy of Rauner Library Special Collections, Dartmouth College, Hanover NH

[iii] Official U.S.S.S. reports of Lt. Col. Casper Trepp (July 29, 1863) and Maj. Homer R. Stoughton (July 27), Berdan Sharpshooters website, http://www.berdansharpshooters.com/links.html, retrieved Nov. 15, 2015;

Allen C. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (New York: Random House Vintage Civil War Library, 2014) 436

[iv] Guelzo, Gettysburg, 430-31; Richard F. Welch, Battle of Gettysburg Finale, “America’s Civil War” magazine, July 1994, re-published online at http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-gettysburg-finale.htm, Retrieved June, 10 2016; Shelby Foote “The Stars in Their Courses: The Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863” (New York: The Modern Library, 1994) 267-68

[v] Guelzo, Gettysburg, 433-36

[vi] Gettysburg Casualties, HistoryNet http://www.historynet.com/gettysburg-casualties Retrieved May 15, 2016

[vii] “The 1862 [US] Army Officer’s Pocket Companion – A Manual for Staff Officers in the field : Article 20” quoted by M.E. Wolf, CIVIL WAR TALK [forum]: http://civilwartalk.com/threads/adjutant-and-aide-de-camp.24884/ Retrieved June 29, 2016

[viii] Timothy J. Orr, On Such Tender Threads does the Fate of Nations Depend: The Second U.S. Sharpshooters Defend the Union Left 122-124 in Papers of the 2006 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar (National Park Service, 2008), http://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/11/index.htm Retrieved November 15, 2015; Ray Marcot, U.S. SharpShooters: Berdan’s Civil War Elite (Mechanicsburg PA: Stackpole Books) 9-15; Drew G. Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and Dying in the Civil War (New York; Vintage Books, 2008) 42

[ix] Orr, On Such Tender Threads… 126-142

[x] Wyman S. White (Ed. Russell C. White) The Civil War Diary of Wyman S. White: First Sergeant, Company F, 2nd United States Sharpshooters (Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 1993) 174-175

[xi] Ibid, 175

[xii] Ibid, 176

There was no “Pickett’s Charge.” It was Robert E. Lee’s Charge, killing a lot of other generals’ people. A large part of the Army of No. Virginia KNEW they were charging into a suicidal position. The South has deliberately mis-named that calamity from then til now.