A Sharpshooter’s Postscript to Gettysburg, Part Two: No Rest for the Weary

Part two in a series.

We welcome back guest author Robert M. Wilson.

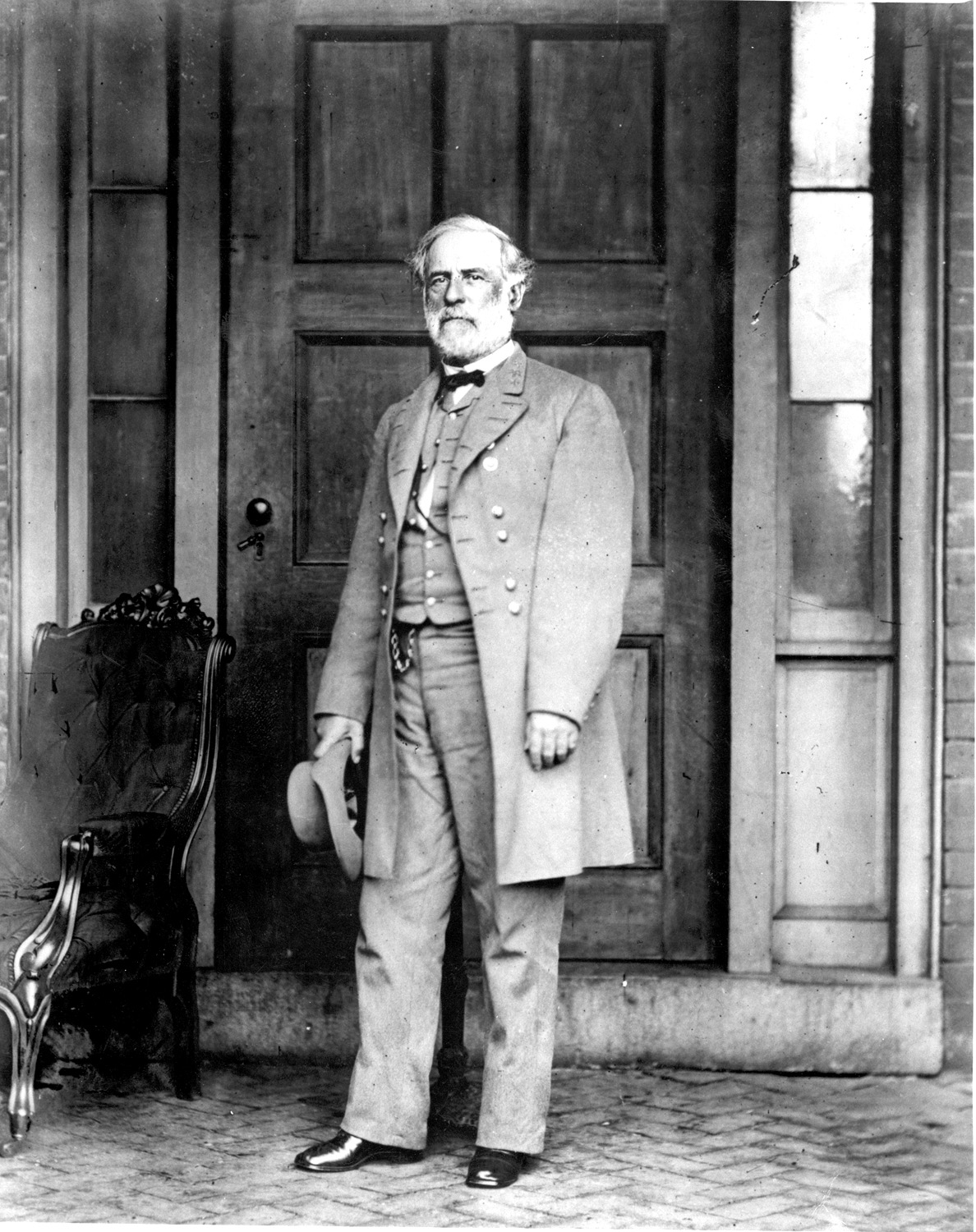

When Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began its retreat from Gettysburg and the Army of the Potomac, under command of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, started the pursuit, both armies were physically and mentally depleted. The soldiers had been marching or riding since the Gettysburg Campaign began in early June from their camps on opposite sides of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia. The Confederates moved first, as Lee launched the bold invasion north into Pennsylvania. Union troops mobilized and followed. After fighting broke out at Gettysburg on July 1, as advance elements of the armies collided at Gettysburg, each side began rushing troops to the town. Regiments on both sides converged on the town and flung themselves into the battle in progress.[i]

Not everyone reached the battlefield in time for the first day’s fight. United States Sharpshooter (U.S.S.S.) Wyman S. White described a 14 mile “forced march” over rough roads that started after noon and arrived after dark on July 1.[ii] He and comrades did not have to wait long for the battle to find them. A horrific and historic day of combat followed on July 2, as all of the Union Third Corps and other units fought hard to check a massive Confederate attack on the federal left flank that ended in the evening. Sharpshooters also helped to oppose the right flank of Pickett’s Charge on July 3.[iii] And for some, including U.S.S.S. Lt. George A. Marden, serving as the Assistant Adjutant General (AAG) for J. Hobart Ward’s Brigade, one more day of fighting followed on Independence Day. He and many others on the battlefield— regardless of their uniform’s color— were wearing down. As he observed in a July 5 letter: “I have not had my boots off for four nights and for forty eight hours of the time had not a mouthful to eat.”

Of those not employed in the fighting and reconnaissance activities of July 4 and 5, White and many others took on the somber task of bringing in, identifying and burying the dead, a physically and emotionally demanding task in itself. The Sharpshooter’s memoir of the war has a gripping description of his burial party crossing the battlefield on at night while on that mission, with no light to guide them save lightning flashes that illuminated the bodies and the ghostly features of their faces.

It was a journey I would not care to repeat and you can imagine our feelings as we were bearing the bodies of our dead comrades, often falling over the bodies of the slain, causing us to drop, for us, our sacred burdens…

When we got to the regiment, they had dug graves, not in the moonbeams’ misty light and lanterns dimly burning, but in entire darkness… [T]hese soldiers buried their comrades’ bodies as tenderly as their mothers could have done. Never was there a more weird funeral and burial ever done…”[iv]

United States Army Center of Military History

As exhausted as everyone was from the previous month’s marching and fighting, when the battle was over there was no rest for the Southerners, and little for their Union counterparts. The main body of the Army of Northern Virginia, centered on Seminary Ridge the night of July4, began its withdrawal that night and was completely gone by dawn the next morning, heading for Williamsport, a town on the Potomac River in Maryland. The federal troops moved out on July 5, 6, or 7 (depending where their Corps was assigned in the order of march). The armies took different routes toward the Potomac, Lee’s men moving to the west and then turning southwards and Meade’s traveling a more easterly series of roads. All the troops, save a relatively small number of Union medical personnel and soldiers staying behind in Gettysburg, were on the march again. Among the Confederate exodus were a number of “walking wounded,” casualties who had been crowded off their wagon train by the more seriously injured.[v]

Third Corps, including Marden’s brigade and Sharpshooters, were ordered to join the pursuit of Lee’s Army on July 7, marching about 17 miles before bivouacking near Mechanicsville, Pennsylvania.[vi] Despite their fatigue, and bouts of rainy weather that made miserable going, many of the Union troops expressed eagerness for battle and hopefulness for bringing an end to the war. Massachusetts artilleryman John Chase claimed he and his comrades were taking the rough going “like Martyrs saying if only we can get at them again before they get to Maryland…” Observing that those exposed to war were rarely “anxious to fight,” another soldier wrote that he and his comrades were “animated by the triumphs of Gettysburg” and wished “with a united voice to be led to the work of carnage” if that’s what it took to finish their foe.[vii]

Marden’s July 5 letter expressed similar conviction, and a hope for reinforcements: “If we don’t wipe out Lee this time it will be Uncle Sam’s fault. Every available man should be brought to bear upon him.” While the resolution remained to finish the job they had started, as the Union soldiers slowly approached Williamsport, terrible rain, mud and heat “like a furnace” took its toll. While the was Army of the Potomac eventually was resupplied and reinforced, it had not been able to refit before the pursuit, and now lacked the supplies needed to refit and nourish adequately its tired ranks. Hardship extended to the highest ranks. “I have not changed my clothes, have not had a regular night’s sleep… no regular food, and all that time in a state of great mental anxiety,” General Meade complained to his wife in a July 8 letter.[viii] When Lt. Marden wrote home about the march to Williamsport on July 13, he was even more dramatic:

I am disgusted. Here we are chasing about “from pillar to post”… with scarcely time to eat a square meal of victuals, if we had them, and not a clean shirt to my back… [T]here is not sustenance enough to keep the rabbits “to the manor born”. Oh! It is too bad!

You ought to see this army. Plenty of men are going along barefoot. My face is about the color of hemlock sole leather. My pants are begrimed with dust sweat and rain until they are nearly waterproof.[ix]

Bad as it may have been for the federal side, Lee’s men had it worse. They struggled with dwindling supplies, exhaustion, and rough roads. In Lee’s own words they had “neither rations or ammunition for the troops or prisoners, nor food for the starving animals, who could scarcely drag themselves through the mud.”[x] They also bore the demoralizing burdens of losing almost a third of their comrades on Gettysburg battlefield and the loss of the battle itself would be to the Confederacy. A southern artillery officer’s assessment of what his comrades were thinking and feeling: “[E]very one feels how disastrous to us our defeat at Gettysburg was, and the retreat has been almost as bad for us as the defeat.”[xi]

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW

To whatever weariness and demoralization the Southerners were feeling, add anxiety. The army marched south hearing that the pontoon troop bridge that some had used to pass over the Potomac to Pennsylvania for their invasion had been destroyed by marauding federal cavalry on July 4, and that the rain-swollen Potomac River was un-fordable. They faced the very real possibility that the place from which they planned to escape into Virginia might turn into a deadly trap.[xii]

Finally, there were the 12,000 Confederate wounded packed into hundreds of wagons and suffering greatly on the bumpy road to Williamsport. There had been no time on July 4 for Lee’s medical staff to properly administer to the wounds of many of the casualties before they were loaded for the journey. The train of wagons in retreat proceeded west and then south, stretching from 15 to 20 miles depending on road conditions, with an escort of cavalry and infantrymen placed under the command of Brig. General John D. Imboden. Along the way, it would be attacked by Union cavalry and in the town of Greencastle, by angry mob of Pennsylvania civilians wielding axes.[xiii]

Endnotes:

[i] Allen C. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (New York: Random House Vintage Civil War Library, 2014) 139-159

[ii] Wyman S. White (Ed. Russell C. White) The Civil War Diary of Wyman S. White: First Sergeant, Company F, 2nd United States Sharpshooters (Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 1993) 161-162

[iii] Ibid., 162-172; Orr, On Such Tender Threads… 126-142; Bradley M. Gottfried, Brigades of Gettysburg: The Union and Confederate Brigades at the Battle of Gettysburg (New York, Skyhorse Publishing, 2002, 2012) 194-201

[iv] White The Civil War Diary 172-173

[v] Allen C. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (New York: Random House Vintage Civil War Library, 2014) 433-437

[vi] White The Civil War Diary 175

[vii] Guelzo, Gettysburg, 446

[viii] Richard F. Welch, Battle of Gettysburg Finale, “America’s Civil War” magazine, July 1994, re-published online at http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-gettysburg-finale.htm, Retrieved June, 10 2016

[ix] Marden, Civil War Letters, July 13

[x] Robert E. Lee, quoted in Guelzo, Gettysburg 437

[xi] General Edward Porter Alexander, Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998 [first published 1989] 269, quoted in Guelzo, Gettysburg, 446

[xii] Tim Rowland, Lee Escapes from Gettysburg originally published in “America’s Civil War” July 2014, HistoryNet http://www.historynet.com/lee-escapes-from-gettysburg.htm retrieved June 30, 2016

[xiii] North Against South, “Imboden’s Wagon Train of the Wounded” http://northagainstsouth.com/imbodens-wagon-train-of-the-wounded/” Retrieved June 20, 2016; Eyewitness to History, “Lee’s Retreat from Gettysburg, 1863”, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/pfgtburg2.htm Retrieved June 10, 2016

Eric Wittenberg’s and JD Petruzzi’s “One Continuous Fight” is a must read if you are interested in the retreat. There is also Kent Masterson Brown’s book on the retreat. Steve French has a great book on Imboden’s brigade which talks about that retreat route. I thought that it was interesting that the soldier had Mechanicsville as being in Pennsylvania when it is in Maryland (present day Thurmont). Both retreat routes are so interesting if you have the chance to follow them along with the Union March.

Thanks for the recommendation on “One Continuous Fight.” I read about it when researching this series and am ordering it. And thanks for the correction on where Mechanicsville is. Wyman White actually didn’t say which state it was in, so I can’t let him take the blame. That was my mistake!

Rob Wilson

Rob. Email me at crdowns@hotmail.com. Would love to talk to you more about the retreat. The town of Wlilliamsport had a bus tour of Imboden’s retreat you’re in 2012 done by Steve French and the Monterey Pass route by Eric Wittenberg. I was able to do both and learned a lot. The Imboden route is toughest to follow. By the way John Miller had done a great job at Monterey Pass (now Blue Ride Summit).

Charlie