Forging a State: The Western Virginia Campaign of July 1861–Part I

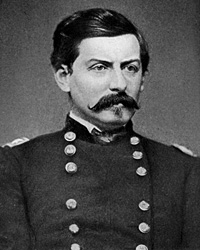

The 1861 Western Virginia Campaigns are a fascinating but vastly overlooked piece of Civil War campaign history. Like many battles fought in that first year, they pale in size when stood up next to Antietam, Gettysburg, or Vicksburg. The battles fought in western Virginia in early July 1861 featured a host of soon-to-be household names, such as George McClellan and William Rosecrans for the Federal side and John Pegram and Robert Garnett for the Confederates. Rugged terrain and poor roads defined the campaign, but drawn out of the campaign’s mud and mountains came the only state to be formed as a direct result of the Civil War.

Three battles: Laurel Hill (July 7-11), Rich Mountain (July 11), and Corrick’s Ford (July 13), made up the fighting for possession of a major east-west route through the mountainous western part of Virginia, the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. This important route was one of the few connections between Virginia’s eastern and western halves in 1861. Completed in 1847, the turnpike tied the Shenandoah Valley to the Ohio River to its west. Parkersburg, the road’s western terminus, sat on the Ohio River and was connected to the ever-important Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad.

Following the Federal victory at Philippi on June 3, 1861, Robert E. Lee, commander of all Virginia forces, appointed Robert Garnett to command the Southern armies in northwestern Virginia. Garnett, 41 years old and a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1841, had an impressive resume. A man whose “every trait was purely military,” Garnett received the dual task of halting the Union advance into western Virginia and striking the B&O Railroad with trepidation. “They have not given me an adequate force. I can do nothing. They have sent me to my death,” he supposedly said before departing for the front.

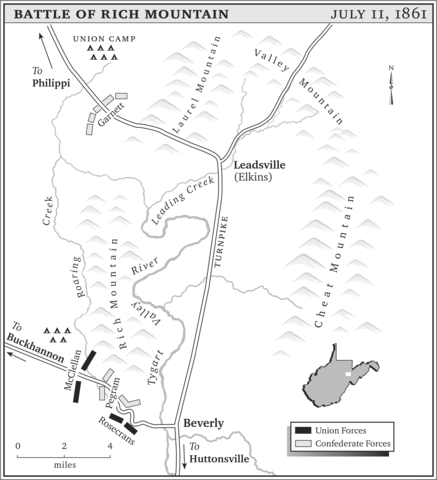

To carry out his goals, Garnett chose to defend two mountain passes. Garnett placed 4,000 men at Camp Laurel Hill northwest of modern-day Elkins, West Virginia, while he dispatched 1,300 men sixteen miles south to Rich Mountain abreast the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. These passes were the “gates to the northwestern country,” said Garnett. He set his men to work fortifying the passes immediately.

George McClellan set to work planning how his Army of Occupation would continue its success in western Virginia. Examining the enemy positions, McClellan determined to turn Garnett’s left flank at Rich Mountain, while holding the rest of the enemy force in place at Laurel Hill with a diversionary attack there. “[I]f possible I will repeat the manoeuvre of Cerro Gordo,” McClellan informed Winfield Scott on July 5. It was a textbook plan.

McClellan tasked Thomas Morris and his Indianans with holding Garnett’s attention at Laurel Hill while he personally took 6,000 men south to the foot of Rich Mountain. Morris arrived opposite the Laurel Hill defenses on July 7 and McClellan reached the foot of Rich Mountain two days later. The stage was set.

I just finished Rebel Yell, by S.C. Gwynne, and this post piggybacked nicely! Good job!

Kevin, Interesting post. I hope you will also cover the parallel campaign in those early days carried out by Jacob Cox which took Charleston and Gauley Bridge.

Nice to hear about Western Virginia in ’61. I enjoyed this post and look forward to learning more as the series continues!

My ancestors lived on the Ohio River near Moundsville and named one of their sons George B. McClellan Hartley and named another Garnett. I always thought Garnett was an unusual name and now I’m wondering if my ancestor fought for the Union under these men…