1860’s Politics: Why Do We think McClellan Was the “Peace Candidate”? Because the Rebels Thought So

A thoughtful respondent to my recent submission to the ECW blog, “1860’s Politics,” wondered why Gen. George McClellan, Democratic nominee for U. S. president in 1864, waited until after Sherman’s troops captured Atlanta, Sept. 2, 1864, before he announced his position on the war: no peace unless the Rebels agreed to return to the Union.

A thoughtful respondent to my recent submission to the ECW blog, “1860’s Politics,” wondered why Gen. George McClellan, Democratic nominee for U. S. president in 1864, waited until after Sherman’s troops captured Atlanta, Sept. 2, 1864, before he announced his position on the war: no peace unless the Rebels agreed to return to the Union.

I answered from Stephen Sears’ George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (1988): that the Democratic convention in Chicago did not open until August 29; that McClellan was not nominated until August 31 (the day Sherman’s infantry cut the last railroad into Atlanta); that Mac went through six drafts of his statement accepting the nomination; and that “from first to last he consistently rejected an unconditional armistice and made reunion a precondition for any peace settlement with the Confederacy” (pp. 373-75).

Clearly the Young Napoleon was the Democratic convention’s “war candidate for president” all along, as Sears writes (374).

So how did he get the rep that he favored peace with the Rebels, and that if elected, he’d pursue an armistice to end the bloodshed after four years of it?Part of the answer, as I wrote last time, was that Republicans’ political propaganda successfully tarnished McClellan with the smear of treason, effectively conveying the idea that a vote for the Democrats was a vote against the Union, and a betrayal of all war-sacrifice to date (J. G. Randall and David Donald, The Divided Union [1961], 477-78).

Another part of the answer was that Confederate Southerners after three years of war so fervently hoped for a negotiated end to it, an armistice with the North which would grant their political independence, that they willed themselves into exaggerating Northerners’ war-weariness. Misinterpreting the Democratic Party’s role in the Northern body politic and the party platform itself proved, ironically, a reflection of Rebels’ own war-weariness.

Confederate awareness of goings-on in Yankeedom was not new in 1864. “From the beginning of the war,” writes Larry E. Nelson in his excellent Bullets, Ballots, and Rhetoric: Confederate Policy for the United States Presidential Contest of 1864 (Tuscaloosa, 1980)…

…reports had reached the Confederacy of tension and malaise in the North: fluctuations in the value of greenbacks, draft resistance and riots, cries of outrage and protests against the emancipation policy, political defeats suffered by the Republicans in the elections of 1862, and growing alienation and discontent in the border states and old Northwest.

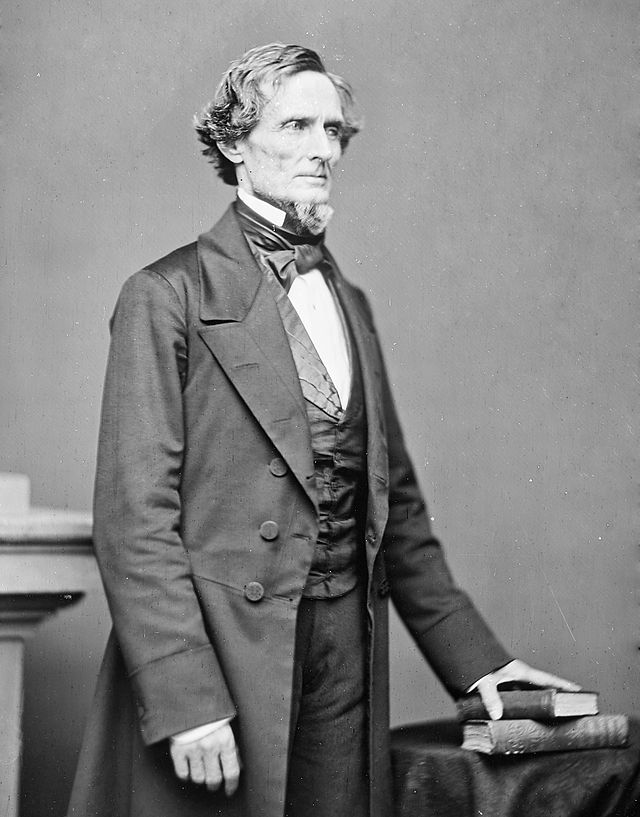

Jefferson Davis early on sensed that the Northern presidential elections of 1864 might offer political opportunities for the Confederacy. He was not alone. Exhausted Southerners built up hopes that, as Nelson writes, “somehow, some way, the election would bring an acceptable peace” (pp. xi-xii).

Understandably, those Northerners starting to bellow “peace” in 1864—Democrats, Copperheads, whoever—attracted Southerners’ attention. One such was Benjamin Harris, peace Democrat from Maryland, who declared on the floor of the U. S. House of Representatives, April 9, 1864, “I am a peace man, a radical peace man; and I am for peace by the recognition of the South, for the recognition of the southern confederacy” (Nelson, p. 6). Just the day before, an Ohio Copperhead, Rep. Alexander Long, asserted in a similar speech, “I am reluctantly and despondingly forced to the conclusion that the Union is lost never to be restored.” Long’s address, including his belief that “the masses of the Democratic party are for peace,” was of course eagerly reprinted in Southern newspapers. One, the Augusta (GA) Chronicle & Sentinel, jumped to the conclusion that Long’s speech would become a basis for the “platform upon which the Democratic party of the North will make the issue in the coming Presidential election” (pp. 5-7).

Confederate soldiers, always avid newspaper readers, picked up on all of this. “The Presidential Campaign is already beginning to open in their papers,” wrote Louisiana Sgt. Edwin H. Fay to his wife Sarah as early as Jan. 9, 1864. “We may be able to hold out Twelve months longer,” he opined,” but I don’t think the Yanks can with the pressure on them” (Bell Irvin Wiley, ed., This Infernal War: The Confederate Letters of Sgt. Edwin H. Fay [Austin TX, 1958], p. 385).

As far away as Paris, Confederate envoy to France John Slidell reported talk he had heard in April 1864 from a French diplomat, who “speaks in strong terms of the growing lassitude of the North and anticipates a general breaking up of the Lincoln Government before the end of the year” (Slidell to Judah Benjamin, Apr. 7, 1864, OR Navies, Ser. 2, vol. 3, 1078).

Leading Confederates even proposed that military operations in 1864 be conducted with an eye to winning victories that would demoralize the Lincolnites and bolster the peace Democrats. In my survey of the Atlanta Campaign, I make much of President Davis’ sending Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton to Dalton in April 1864 to impress upon Gen Joe Johnston the need to take the offensive against the Yankees in the spring campaign. Pendleton stressed the importance of aggressive action against the enemy in Tennessee: “to break up his plans….to press him….to beat him” (Davis, Atlanta Will Fall: Sherman, Joe Johnston, and the Yankee Heavy Battalions [2001], p. 31). After meeting with Johnston on April 15, Pendleton wrote a long memorandum to the president recording his conversation. The general had made clear to Johnston that a proposed offensive, if launched, would have important psychological benefits: it would “inspirit” Johnston’s army and the Southern people, as well as “depress the enemy, involving greatest results” (Dunbar Rowland, ed., Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist [Jackson MS, 1923], vol. 6, 228). Nelson sees Pendleton’s mission to get Johnston moving forward as having both military and political purposes. As he puts it, it was “an illustration of the president’s confidence in the coincidence of objectives for the Northern election and existing Confederate military policy” (Bullets, Ballots, and Rhetoric, 26).

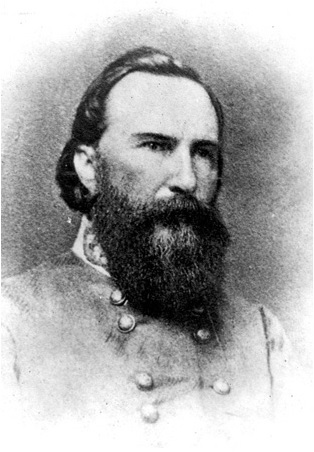

As President Davis and General Johnston (joined by Secretary of War James A. Seddon and Gen. Braxton Bragg) sent letters back and forth in the winter of ’64 on the hope that Johnston could march into Tennessee, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet thought he had a good idea and laid it out in a letter to General Beauregard in March 1864. Longstreet at the time commanded a small army in east Tennessee, which he proposed to lead forward even into Kentucky in concert with Johnston. Pete, like other Confederates, had Northern politics in mind:

If we go into Kentucky, and can there unite with General Johnston’s army, we shall have force enough to hold it. The enemy will be more or less demoralize and disheartened by the great loss of territory which he will sustain, and he will find great difficulty in getting men enough to operate with before the elections in the fall, when in all probability Lincoln will be defeated and peace will follow in the spring.

(Longstreet to Thomas Jordan, Mar. 27, 1864, OR, vol. 32, pt. 3, 679; see also William Garrett Piston, Lee’s Tarnished Lieutenant: James Longstreet and His Place in Southern History [Athens GA, 1987], 83-85).

Jefferson Davis once famously declared to the Southern people, “We have but to will it and we will be free.” Well, given what we know today, it would have taken a whole lot of willin’ for Confederate Southerners to turn Lincoln’s defeat and George McClellan’s electoral victory into peace and independence for themselves in the spring of 1865.

But, boy, did they try.

Because . . . Confederates.