Longstreet Goes West, part nine: The November of our discontent

Both Bragg and Longstreet – indeed every Confederate from Richmond on down – understood that to be successful, any movement into East Tennessee must be conducted quickly, and in sufficient strength. The idea was to deliver a rapid knock-out blow against Ambrose Burnside, and then turn and deal with Grant.

Both Bragg and Longstreet – indeed every Confederate from Richmond on down – understood that to be successful, any movement into East Tennessee must be conducted quickly, and in sufficient strength. The idea was to deliver a rapid knock-out blow against Ambrose Burnside, and then turn and deal with Grant.

The fundamental military advantage gained by interior lines, however, is negated if the requisite speed and force needed to gain that knock-out blow are not also part of the equation. In East Tennessee, Longstreet was neither fast enough, nor strong enough.

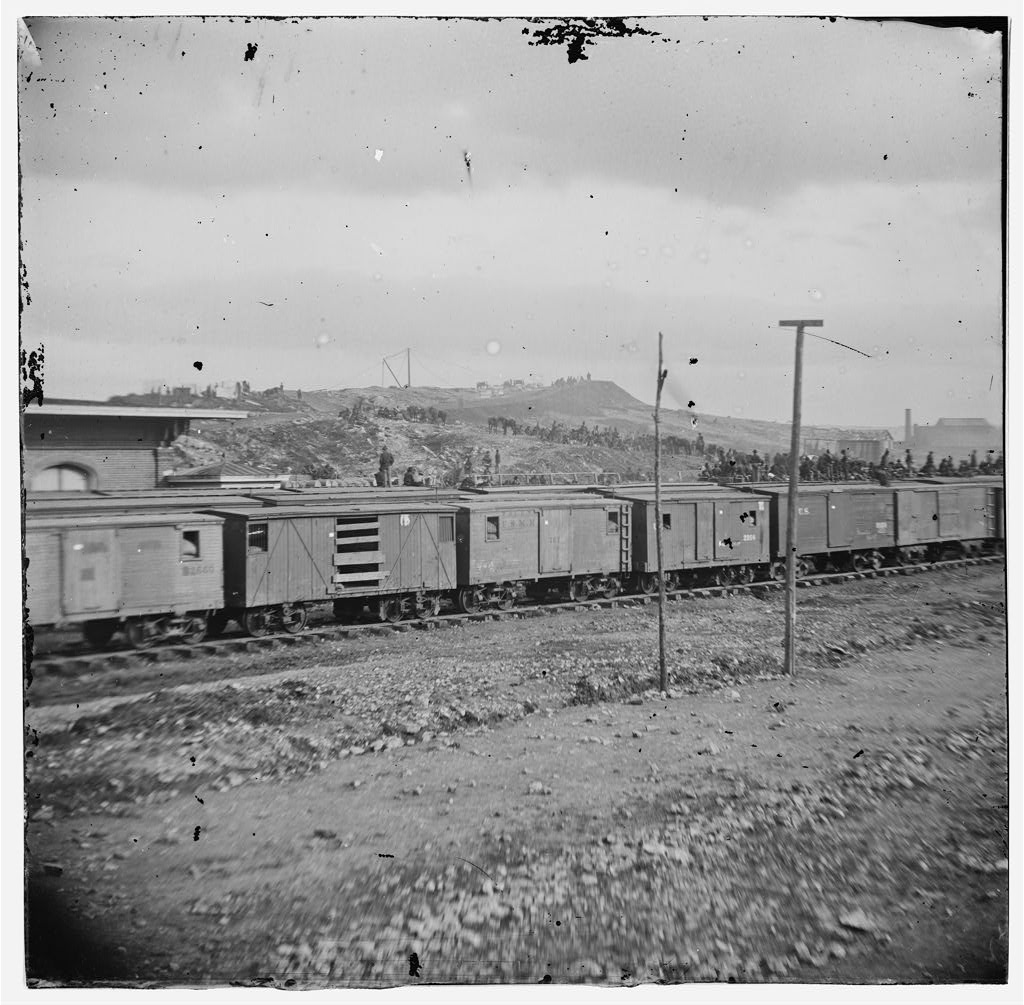

We have already touched on the logistical complications of Longstreet’s movement to Sweetwater. The rail move, which was theoretically the easiest portion of that redeployment, proved a nightmare. The condition of the locomotives, the cars, and the track were all dire. Engines couldn’t haul the loaded cars up certain grades, forcing the men to halt and march alongside the tracks while the empty trains wheezed alongside. Wood was in short supply, forcing troops to halt and forage for timber – often at the expense of nearby farm fencing. Not until November 12 were the bulk of Longstreet’s men assembled at Sweetwater, with his artillery and supply trains (such as it was) still coming up.

By the 12th, Longstreet’s force numbered 12,000 infantry and artillery. It also included “portions” of four brigades of cavalry (roughly 5,000 men) commanded by Joseph Wheeler, who further described his force as “much worn and depleted by . . . arduous service.” Though the overall Federal force was considerably larger (25,600, by the November 30 return) they were also more scattered; against Longstreet Burnside could only concentrate about 12,500 infantry and no more than 3,000 of his 8,000 available cavalry.

Union intelligence also greatly exaggerated the Rebel threat. Charles A. Dana, who Grant dispatched to Knoxville in mid-November to report on conditions there, wired at 4:00 p.m. on the 12th that “it is certain that Longstreet is approaching from Chattanooga with from 20,000 to 40,000 troops. Though his numbers were not terribly inaccurate (Longstreet had 12,000, Stevenson mustered about 10,000, and Wheeler was estimated at 7,000; all told, 29,000 men)

What Dana could not know was that that Stevenson was being recalled, or that Wheeler’s cavalry were in such a parlous state.

Despite all these difficulties, Longstreet resolved to move on November 13. The big Georgian wanted to sidle up the south bank of the Tennessee River, outflanking Burnside’s advance guard, and fall on Knoxville unexpectedly. Once again, his plans foundered on logistics.

Moving up the south bank would require three major river crossings. First came the Little Tennessee River, then the Little River, and finally, Longstreet would have to cross to the north bank of the Tennessee River somewhere close to Knoxville – all of which would require pontoons. While he had sufficient pontoons, Longstreet lacked the animals to draw them. His pontoon bridge could only be moved by rail; no rail line, operable or otherwise, ran along the south bank.

Longstreet could float the pontoons directly off the train cars downstream to cross to the north bank of the Tennessee near Loudoun, which would then put him on the same side of the river as Knoxville (and the rail line he was charged with repairing) but it would also mean confronting Burnside’s main strength head-on, instead of turning Burnside’s flank. He had little other choice.

Not prepared to entirely give up on his preferred strategy, Longstreet settled for sending Wheeler up the south bank. The Rebel cavalry was to capture the town of Maryville, and then at least threaten Knoxville from the south. Even if he failed to take the city, Wheeler might draw off some of Burnside’s force.

At dusk on November 13 South Carolinians from the Palmetto Sharpshooters crossed the Tennessee at Hough’s (or Huff’s) Ferry. By dawn on the 14th, a bridge – of sorts – was up. Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet’s chief of staff, described that rickety structure as “a sight to remember. The current was strong, the anchorage insufficient, the boats and indeed entire outfit quite primitive, and when lashed finally to both banks it might be imagined . . . [to be] a huge letter ‘S.’”

Still, it served. Longstreet’s main body crossed on November 14, though navigating that torturous bridge took most of the day. Alerted by the activity, General Burnside rode the rails to Lenoir Station, where he was assembling about 9,000 troops. He hoped to catch Longstreet while crossing, but that did not happen. Instead Burnside cautiously advanced in the afternoon, but the only conflict came when a small Union force skirmished with Bratton’s brigade of Confederates. Eschewing any larger assault, Burnside decided to fall on Lenoir’s Station; and ultimately, retire to Knoxville.

On November 15, Longstreet pursued to Lenoir’s, attempting to flank Burnside before he could retreat. That maneuver failed. Longstreet had no useful maps, his guides (provided by Bragg) seemed inept, and his remaining cavalry (John Hart’s Georgia Brigade, of Wheeler) provided no useful reconnaissance. The weather was also a factor, though it effected both sides: the mud was so bad that Union guns could only be moved by assigning platoons of infantrymen to help push them along. Burnside, however, possessed the direct road to Knoxville, and the railroad besides; any flanking effort Longstreet could mount – even assuming he figured out the roads – would require longer and even more arduous marches than Burnside’s men faced.

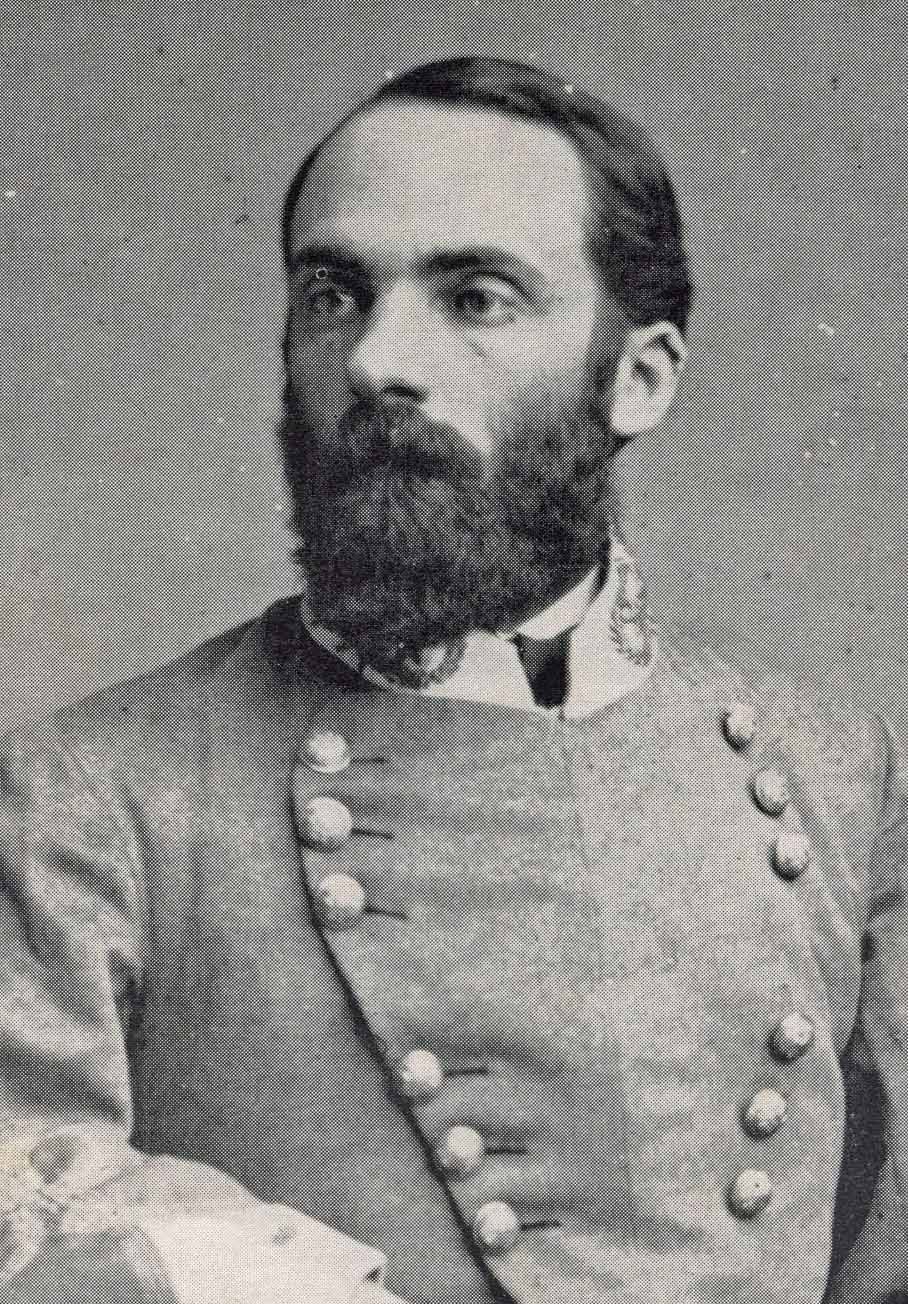

Unsurprisingly, Longstreet failed to catch the Federals, though they did fight a sharp action at Campbell’s Station on November 16. There Longstreet’s column caught up with the Union rearguard and attacked. Aggressively, Longstreet attempted a double envelopment. McLaws’ division delivered a spirited attack, but Jenkins’ division failed to come up on time. The Federals got away, while the Rebel miscue only fed more internal dissent between Jenkins and Evander Law.

In the meanwhile, Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry captured Maryville, and, with Union cavalry skirmishing along the way, reached the south bank of the Tennessee opposite Knoxville by the afternoon of the 15th. There Rebel cavalryman probed the Federal defenses, well-sited on the town’s southernmost heights, both that afternoon the next morning, but failed to achieve any real result. Late on the 15th Wheeler received a dispatch from Longstreet, who wrote that “unless you [Wheeler] are doing better service by moving along on the enemy’s flank than you can do here, I would rather you should join us and co-operate.”

Despite later reporting that he had routed the opposing cavalry quite handily (seemingly an exaggeration) Wheeler was clearly stymied by the Union defenses, and elected to instead move back downstream, where on November 17 he crossed to the north bank of the Tennessee at the town of Louisville (about halfway between Knoxville and Campbell’s Station.) He rendezvoused with Longstreet at 3:00 p.m.

By that time, Burnside’s entire force had successfully fallen back within the defenses of Knoxville. Behind Union Engineer Orlando Poe’s excellent works, Burnside’s army now outnumbered Longstreet’s expeditionary force, was better provisioned, having been preparing for a potential siege for some weeks, and possessed of far more decent living quarters than the Confederates were likely to find – a significant factor in during the cold, rainy November ahead.

Despite the logistical difficulties, Longstreet’s small army made surprisingly good time covering the distance between Sweetwater and Knoxville, roughly 45 miles apart – approximately 72 hours, including skirmishes at Lenoir’s and a stiff fight at Campbell’s Station.

It was all for naught. Longstreet lacked the force to completely encircle Burnside, meaning that the Federals were never cut off from re-provisioning, and his 9,000 effective infantry (the Rebels suffered nearly 600 casualties so far, and illness was also taking a toll) were too few for a direct assault. He postponed just such an effort on November 20. Somewhat surprisingly, over the course of the next week, Bragg proposed to send him another 3,500 men under Bushrod Johnson; and, more daringly, one of the Army of Tennessee’s finest commands, Patrick Cleburne’s division. The lead elements of Johnson’s force departed for Knoxville on November 23rd.

Then disaster struck, in the form of Ulysses S. Grant. Opening with an advance to Orchard Knob on the 23rd, following with an attack on Lookout Mountain on the 24th, and concluding with a series of devastating assaults against Missionary Ridge on the 25th, Grant shattered Bragg’s army and drove it back to Dalton in disorganized, chaotic retreat. If Bragg had not stopped Cleburne’s departure in the nick of time, that officer would not have been present to first stop William T. Sherman’s attack on the 25th, and then save Bragg’s whole army with a valiant rear-guard action at Ringgold on the 27th.

One of the lesser-known but important actions of Grant’s plan involved sending 1,500 Federal troopers under Col. Eli Long of the 4th Ohio Cavalry to destroy or damage the East Tennessee Railroad at Cleveland. Long reached Cleveland on November 26, and after driving off a brigade of Confederate horsemen, proceeded to wreak considerable havoc. Long’s men destroyed a copper rolling mill, large quantities of foodstuffs and ammunition, and tore up considerable track. This last bit of destruction was the most important; doing so rendered it impossible for Longstreet to return to Chattanooga, either to help Bragg or to fall on the Union flank.

On November 23rd, Longstreet also received Brigadier General Danville Leadbetter, chief engineer for the Army of Tennessee, who had originally laid out the Confederate defenses at Knoxville. Leadbetter was there to convey Bragg’s views. He was to help Longstreet find a way to attack Knoxville and overwhelm the defenders, thus avoiding a long siege; or if that was not possible, instruct Longstreet to rejoin Bragg.

Leadbetter’s effect on the campaign was curious. His advice to Longstreet was ambiguous, waffling between two objectives. On the northwest corner of the Union line stood Fort Sanders. On the northeast corner, Mabry’s Hill. Leadbetter couldn’t decide which was more vulnerable. The truth was that there were no good approaches, which several days of scouting revealed, but Fort Sanders was the most likely of a bad bunch. On November 28, Longstreet ordered McLaws to make the attack.

The assault on Fort Sanders represents a nadir of both Confederate planning and execution. One key issue, for example, was the depth of the ditch in front of the fort’s glacis. Leadbetter told Longstreet that the Confederate Fort Loudon (upon which Sanders was built) had no ditch at all. Confederate observers saw men and animals routinely crossed the ditch easily, suggesting that it was no more than waist-deep on a man. McLaws’s staffers dismissed the ditch as ‘a mere scratching.” It wasn’t.

Of course, the Confederates had little else to go on but wishful thinking. McLaws himself proposed building fascines out of shocks of wheat, but the Confederates could find no wheat. Scaling ladders were similarly proposed; but the troops had no tools with which to make them. Once again planning foundered on a lack of even the simplest resources.

The attack was a bloody failure. The Rebels lost 813 men; the Yankees, 13. The ditch was 12 feet deep and 8 feet wide. Longstreet’s suggested idea that the attackers could dig hand- and foot-holds in the fort wall in lieu of ladders was clearly impractical.

Adding to the pressure to make the assault was the understanding that Bragg had been badly defeated at Missionary Ridge. First intimation that affairs at Chattanooga had taken an active turn came with Leadbetter. Barely an hour after the repulse at Fort Sanders, Longstreet received a relayed telegram from Jefferson Davis, ordering him to break of the siege and march immediately to rejoin Bragg, who had been badly defeated.

Longstreet took steps to comply the next day, but soon had second thoughts. Even Bragg had doubts that Longstreet could join him at Dalton. Bragg’s force numbered no more than 40,000. Longstreet had perhaps 18,000, counting the reinforcements and cavalry. Grant’s army, now numbering an estimated 80,000 or more, lay directly between Longstreet and Bragg, controlling the only good route through East Tennessee. The railroad was no help, badly damaged and now in Union hands. Longstreet’s options would be to march against Grant head-on with a vastly inferior force, or to slip southwest through barren mountain country, without adequate wagons and no hope of forage along the way. Davis’s order was an invitation to complete disaster.

Instead, after several more days of siege, Longstreet retreated farther to the northeast, towards Virginia, where he still had a viable rail connection. His decision to linger at Knoxville also drew some benefit; for as soon as Bragg retreated Grant dispatched 25,000 men northward to succor Burnside and lift the Knoxville siege, though as it turned out Burnside was never in any real danger of starvation or surrender. But those 25,000 Federals would not be moving against Bragg’s badly disorganized force at Dalton.

Longstreet’s small army lingered in East Tennessee until the end of February. They eventually rejoined Robert E. Lee in Virginia. Throughout the winter, Longstreet’s presence continued to be a thorn in Grant’s side, with the Union commander under pressure to clear East Tennessee of Rebel troops once and for all. Threatening moves and at least one more battle – Bean’s Station, on December 14, which produced 700 Union and 900 Confederate casualties – marked the rest of the campaign, but nothing much came of any of it. When, on March 8, 1864, Longstreet boarded a train taking him east to confer with Lee at Orange Court House, Longstreet’s sojourn in the west was over.

So, too, was Braxton Bragg’s tenure as commander of the Army of Tennessee. Bragg offered his resignation on November 29, the same day McLaws’ men were unsuccessfully storming Fort Sanders. Davis accepted Bragg’s offer immediately. Within two months, Joseph E. Johnston – the man Longstreet had agitated for so long to serve under – took command at Dalton.

Dave:

You are to be congratulated on your excellent 9-part series. I especially liked your emphasis on logistics. I now have a much fuller understanding of the formidable obstacles faced by Union and Rebel generals in barren East Tennessee.

Have you thought about incorporating this series into book form?

Bob, much of this will be in my book on Chattanooga for the Emerging Civil War Series. There is no campaign of the war, IMO, that is more driven by logistical limitations than that of trying capture/defend Chattanooga.

Absolutely, Chattanooga was never going to be taken by Bragg by direct assault. Rosecrans had built a formidable position at Chattanooga with his flanks anchored to the river. It had to be unhinged indirectly. The decisive point to do this was Bridgeport, AL, which was what we call in the Army the “force flow entry point” for the Union logistics into the operational area. Longstreet tried to get Bragg to understand this, but to no avail. Had they gone after Bridgeport in time, i.e. before Hooker moved into Lookout Valley and shut down Bridgeport, then Chattanooga would have had to be abandoned by then Thomas.

The first mistake in the events at Chickamauga and Chattanooga was for Bragg not to reinforce Longstreet after his breakthrough in order for him to force Snodgrass Hill and get the gaps in Missionary Ridge closed – and bag the whole lot of the Army of the Cumberland (as well as use his cavalry arm to help with this such as tell Wheeler and Forrest to get to those gaps ASAP). The second mistake (the second chance) was not to seize Bridgeport, AL early enough so that Chattanooga could be unhinged and Grant could not gather the forces in the area and ultimately overmatch Bragg.

The Knoxville expedition had its purpose, which was primarily to get Longstreet on his way back to Lee since the 1st Corps Army of Northern Virginia was OPCON (Operational Control) to Bragg for the western concentration attempt in September and make an effort to seize Knoxville if possible during the repositioning. This, in turn, might prevent Grant from attacking Bragg, in that he might have to send Sherman to go after Longstreet if Knoxville fell. Logistics would hobble Longstreet’s movement to Knoxville (he came to GA without wagons). Despite a difficult movement and almost catching Burnside outside his defenses at Campbell’s station, Longstreet was able to tie down Burnside and attempted an assault on a corner of Ft. Sanders. The angle he attempted was correct, but McLaws was right they should have had scaling ladders. At least made something out of branches to walk on. The much higher sides than estimated of Ft. Sanders had frost on them during the attack and the men could not get up its side in their smooth soled shoes.

Longstreet knew a Ft. like this was not easily taken, and normally would not have risked it, but he felt he had to try, as Bragg was now in serious trouble with Grant seizing the initiative. An attack on Bragg would come anytime, and if he could penetrate the defenses and take Knoxville, Grant might have to divert his focus to Knoxville instead of Bragg for a while.