A Visit to the Gettysburg Cyclorama

I’d seen the Gettysburg Cyclorama once before — while in high school and on my way to Washington, D.C.—but had virtually no appreciation for the events it displays. Suppressed by a senior trip agenda, my last stop in Gettysburg was nothing short of a quick stroll around the battlefield’s grounds. There was little time for reflection and, in turn, understanding.

I’d seen the Gettysburg Cyclorama once before — while in high school and on my way to Washington, D.C.—but had virtually no appreciation for the events it displays. Suppressed by a senior trip agenda, my last stop in Gettysburg was nothing short of a quick stroll around the battlefield’s grounds. There was little time for reflection and, in turn, understanding.

This time, though, I’m coming with a purpose: to meet a man who can arguably answer any cyclorama-based question I can conjure. And so, I approach Gettysburg National Military Park’s red, barn-looking visitor center, which houses the cyclorama, to find Chris Brenneman, co-author of The Gettysburg Cyclorama, waiting for me outside the building’s entrance.

Chris’ storytelling begins immediately, as his steady hand reaches out for an affirming handshake. “You must be Liam!” he says.

Wearing a Gettysburg baseball cap, a navy windbreaker, and khakis, Chris leads me up a winding ramp towards the facility housing what I’ve driven nearly five hours to see: the cyclorama. Chris walks with a sense of purpose. It’s clear he cares about educating me and, presumably, others.

While I expect the cyclorama will be “cool,” over the next hour, Chris will give me a far-deeper appreciation for it—its astounding composition, educational offerings, historic background, and well-planned restorations.

As we walk through the visitor center’s entrance and into what’s quite literally the headquarters for his life’s work, Chris describes the history of the building and all the exhibits it houses. He explains that, within that single building, there are 12 Gettysburg-related museum exhibits, along with a large theater, the cyclorama, and (of course) a gift shop. There, Chris’ definitive cyclorama book sits upright on a table within eyes’ sight, right where he’d been doing signings just before our meeting.

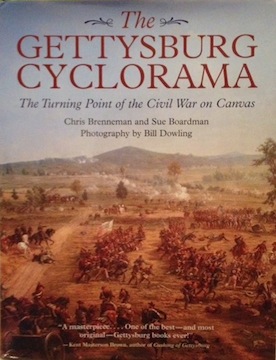

The Gettysburg Cyclorama, co-written with Sue Boardman—who, like Chris, is a licensed battlefield guide—takes a critical look at this historic piece of artwork in not only literal terms, but in light of its messages and the artists’ intentions, too.

Beginning with an explanation of the painting’s creation—from drafts of the painting to the preparation of the canvas to the transfer of the image to the transportation of the final product—readers get a full understanding of the work involved. The authors also delve into the history of cycloramas in the United States, restorations made to this specific cyclorama, and an array of other topics that provide a fully comprehensive context.

In their most fascinating move, the authors sectioned the painting into 10 frames—with the help of photographer Bill Dowling—in order to deconstruct the painting’s depictions from left to right. Dowling even took modern-day photos of the battlefield, intended to mirror the author’s discussions of the grounds at the time.

Needless to say, with knowledge of Brenneman’s extensive research on this singular piece of art, I can’t help but feel I’m standing with some sort of Gettysburg superhero. And with nothing more than elementary knowledge of the war, I perspire, hoping to sound competent enough to have a meaningful conversation with Chris.

Within our first five minutes together, Chris has already let me know he might have to cut our time together short: as a license battlefield guide, he might be scheduled to give another tour of the battlefield. I also quickly come to understand that Chris lives and breathes Gettysburg. Really, Gettysburg’s his child, in a sense. He’s spent years acquainting himself with it and, now, helps maintain and preserve the ground’s story.

Despite this hectic schedule, Chris has still made time to enlighten me. And so, we make our way through some sort of top-secret employee entrance and underneath the cyclorama’s observation deck.

* * *

For the majority of our time in the exhibit, Chris and I stand along the bottom edge of the painting, out of observers’ point of view and, ironically, at the best viewpoint to fully understand the intricacies of the operation.

For the majority of our time in the exhibit, Chris and I stand along the bottom edge of the painting, out of observers’ point of view and, ironically, at the best viewpoint to fully understand the intricacies of the operation.

Pulled downwards by 35-pound weights that hang along its bottom every three feet and hung above from industrial clamps, the Gettysburg Cyclorama towers over us. The 360-degree, climatic panorama depicts Pickett’s Charge on July 3, 1863. at the so-called “High Water Mark.”

It’s strange to think one of the most impactful, storytelling depictions of a major historic event is within arms’ reach.

I can’t help but recall the many museums I’ve visited in my lifetime. Traditionally, artwork is shielded by a glass case, high-tech sensors or security guards. Here, history’s out in the open, begging to be explored.

Chris, like some sort of mad-scientist historian, takes me back in time, explaining the painting’s history.

Commissioned by Chicago merchant Charles Willoughby, the piece is the only surviving in a collection of four paintings, he tells. And, somehow, although it’s 377 feet in length—and almost displays greater detail than a portrait—the piece only took a year and a half to complete.

“Only just over a year?” I ask, almost cutting him off out of amazement. I can hardly believe him. It used to take me weeks to complete an acrylic, 8×10 painting in my high school art classes.

It turns out Paul Philippoteaux, the artistic mastermind behind the work, commissioned 15 to 20 artists for the effort. Still, I’d imagine that selection process could have taken a year itself.

As far as the piece’s creative quality goes, it’s a knockout. I’ve never been drawn to realist artwork—I’m more of a MoMA type of guy—but this piece is arguably more captivating than any Dali or Picasso I’ve laid my eyes on. And, for that reason, I can’t force my gaze away from the painting, as if I’m under some sort of damsel-in-distress curse.

I’m wonderstruck.

Whether viewed from underneath or at eye-level, from arm’s length or the actual observation deck, the panoramic-style piece feels mobile. The 20,000 oil-painted horses and men appear to jump off the canvas, all with stories of their own.

This sense of mobility, Chris says, leads some patrons to question what they’re seeing.

“In this, it really makes you feel like you’re a part of the action,” he says. “Some people don’t believe it’s a painting.”

The painting was made to be viewed in its current capacity, from a deck and with sonic and visual aids, Chris explains. The painting becomes a stationary movie, idle but appearing active with the addition of spotlights to illuminate both fallen and triumphant men, smoke to exaggerate explosions and sound effects to bring the high-intensity action to an otherwise dull room. That’s Chris’ favorite part of the cyclorama.

“The horses look like they could leap right out at you,” he continues. “The guys are running, they’re helping a buddy, giving aid to wounded guys, capturing prisoners. Everyone in the painting is doing something, yet I don’t see two guys doing the same thing.”

Inevitably, after giving me a look at the piece from underneath the viewers’ lines of sight, Chris must take off for his next tour. He leaves me, however, with a better understanding of the cyclorama’s history—and a ticket to see the action as a regular observer.

* * *

I make my way to the visitor center’s theatre for a viewing of “A New Birth of Freedom,” which precedes the full, cyclorama experience. The 20-minute film, laden with old photographs and accounts—and narrated by Morgan Freeman—explains southern tension during slave-holding times. The narrative moves through slavery’s beginning, ethical questioning, and clear hand in the start of the Civil War. It then summarizes the war up to Gettysburg before focusing in on the three-day battle itself.

I make my way to the visitor center’s theatre for a viewing of “A New Birth of Freedom,” which precedes the full, cyclorama experience. The 20-minute film, laden with old photographs and accounts—and narrated by Morgan Freeman—explains southern tension during slave-holding times. The narrative moves through slavery’s beginning, ethical questioning, and clear hand in the start of the Civil War. It then summarizes the war up to Gettysburg before focusing in on the three-day battle itself.

The movie ends and I’m impassioned.

Now, it’s time for me to see the cyclorama’s action for the first time in nearly three years—with a very different understanding this time.

I follow the flood of the crowd up a dimly lit escalator and into the cyclorama. Immediately, I get a sense of elevation. I must be standing at least 15 feet above my prior location, when I stood at the painting’s bottom, yet the piece’s overwhelming, wrap-around nature is just as affecting.

The show begins at dawn, and I’m right in the action—thankfully not fighting, but instead appreciating the experiences of the men on that battlefield. I think of the families of those men, their pasts and, for some, the futures they’d never see.

It clicks. The cyclorama is an all-inclusive experience.

Sure, my behind-the-scenes look helped heighten my appreciation for the piece. But the set-up provided by the preceding film and the visual and sonic aides within the cyclorama itself bring viewers onto the battlefield—and not in the modern day, but rather, during those days when blood was shed, lives were lost, and history was made.

If you are in Gettysburg on a date when the Gettysburg Foundation offers the special tour “An Evening With The Painting,” do plan to attend. The session we attended, a lecture and tour led by Mr. Brenneman’s co-author, Ms. Boardman, was enthralling. It’s a must-see program for anyone interested in the Gettysburg Cyclorama or in Civil War art in general.

Excellent post. I posted the entire cyclorama several years ago online using an old foldout postcard book that bought as a souvenir as a young boy. Scroll to the right to view the entire piece: http://www.pinstripepress.net/CycloramaScroll.htm

– Michael Aubrecht