Photographic History in Full Color

Colorizing vintage photographs is an intriguing practice among Civil War buffs—but it’s also a war of worth, where digital artists weigh potential historical inaccuracies against heightened storytelling.

For many colorization experts and historians, ineffective practice can jeopardize the representation of well-known figures, the common man, and both groups’ larger historical contexts.

And, so, it seems that, when evaluating a black-and-white image, there’s one fundamental issue at hand: Does color’s addition add heightened value to the image in question? And “value” isn’t necessarily weighed in terms of “pleasing asthenic.”

At the end of the sesquicentennial commemorations, Blood and Glory: The Civil War in Color revealed 500 transformed, cataclysmic conflict images, according to James Brookes, Emerging Civil War’s resident photography expert. The images, he said, displayed the triumphs and pitfalls of colorization.

“They provided a striking new lens with which to view many of the familiar photographs we associate with the conflict,” Brookes said. “But others seemed lackluster, stripped of the haunting detail that is offered so boldly in a monochrome image and replaced with broad brushes of flat color.”

Brookes mentioned that there’s a spectrum of ethical issues in the practice.

The discoloring of a watch or pair of socks might not change historical context in some cases, he said; however, unknowingly misrepresenting or altering skin tones is “a dangerous ethical practice to engage in,” as these racial differences often impact social contexts.

John Roche, the co-owner of Slingshot Studio, a professional colorization service, said skin toning can be one of the trickiest tasks to overcome for that very reason. In turn, “people watching” has become a regular pastime for him—and, presumably, many others in the field.

“If you just take pictures of faces, all of a sudden you’ll find out you have a catalogue of faces,” he said. “I don’t actually use the faces, but it’s a reference.”

It doesn’t stop with faces, though. Detailed colorizing entails reference points for every component of the image at hand — from the color of a soldier’s button to the shade of a civilian’s coat.

Roche added that he finds these references through simple Google searches, intensive research, or in one of the nearly 100 reference folders on his own personal computer—files comprised of sample images he’s taken from random encounters.

“I have folders for skies and then I break them down into cloudy skies, fluffy white clouds, stormy,” he said. “It’s like a diary.”

David Richardson, the owner of History in Full Color, another colorization service, said he’s created a log of sample photos, as well.

According to Roche, these sample images are taken in a number of capacities: on-sight from daily findings, from existing subjects in images and from curator-provided images of existing artifacts.

Richardson explained that in colorizing skin tone specifically, he starts with the same peach color in Photoshop—regardless whether one is of caucasian or other another descent. Then, creating a new layer in the program, he paints over subjects’ faces.

After, depending on the image, he chooses from a variety of options in Photoshop’s “blending mode,” which allows for the program to take into account variations in skin toning and, in turn, race.

The product: the colorization of a black-and-white image.

Some still find fault in the guesswork involved in colorizing the finer details, though, which, sometimes, can’t be entirely precise.

Alex Burnham, a UK-based wet plate photographer, said even the discoloration of leaves on a tree can misrepresent historical context, and that’s why he’s not sold on the value of this practice.

“Just to get the trees in the background of a photograph correct, one would need to research what species of tree they were, what time of year it was, what the rough rainfalls and soil quality for that location were, and even then, minute differences in location and atmosphere could change the shade that the leaves should be colored . . .” Burnham said. “This misinformed change of date could confuse a spectator who did not know when or where that photo was taken, so even slight discrepancies in colorization can have huge impacts on how the image is viewed.”

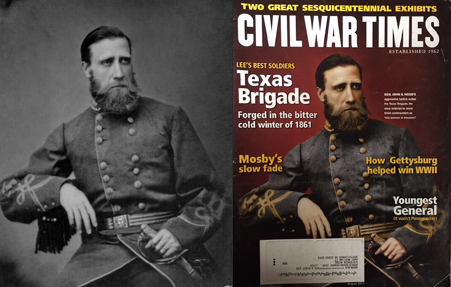

Regardless of discrepancies in factual accuracy, colorization—especially when “fronting” a publication (that is, appearing on the cover)—lends itself to heightened sales for publications existing in a digital age of saturated photo filters. And, perhaps, that fuels the modern push for this practice.

“Coloring images helps us develop bright images that ‘pop’ on the newsstand,” says Civil War Times editor Dana Shoaf.“Colorization has come a long way in the past few years, and a good colorist can accurately use color that feels authentic.”

Still, for Burnham, arguments of better storytelling and better sales don’t excuse the unwarranted adjustments often made to historic images. Burnham added that historians ought to scoff at and work against colorization.

“Historically, artistically and practically speaking, adding color to historical black-and-white photographs is potentially an irresponsible, unhelpful, misguiding and disrespectful practice,” Burnham said. “They cannot be used as true sources of historical evidence and may in the future cloud the interpretations of historians and the public alike.”

And, so, it seems that the argument over what constitutes “value” in colorization is best handled on a case-by-case basis—where more easily and accurately colorized images are published and those better fit for film remain in their original glory.

Interesting article that shed much light on the subject. Remember the old days with colorized movies by ted turner? glad the process has matured.

I had the same thought. However, like Turner’s colorization of Casablanca, I’m inclined to think that many of these colorizations simply mar the original.

The benefit of colorizations is to be able to view more distinct details that you can’t see in the original black and white photography

I like every step of the colorization process except the colorizing. All of the steps leading up to the coloring are about the picture itself. The colorizing is about the modern day artist’s interpretation of the photo.

I do not have an issue with colorized–or otherwise manipulated–pictures on magazine covers. Photographic research is expensive, and there has to be a way for some money to be made. If a colorized photo on the cover attracts more readers, that’s a good thing. I do not have a problem with them being on the page before the article starts However, i do have a problem with colorized photos being used or put in the body of an article.

It’s been interesting to see the colorized photos in the last few years, but I’m still a fan of the black/white/gray old style for Civil War photography.