Civil War, Chemistry, and Football?

Civil War battles are complex things. When leading folks around a battlefield, I (as I’m sure all of you do) try to make complicated movements of thousands of men simple, and draw ideas from these places that they can relate to in their own modern lives. One line I tend to draw quite often between Civil War battles and today’s world dives into football. Yes, you read that correctly. So how is chemistry a part of any of this? Bear with me.

In the middle of every summer, while many of you are, like me, out hoofing endless miles on battlefields across the nation, 32 teams in the National Football League begin their respective training camps, gearing them up for the season to come, getting in shape to prevent injury, and working to reach their peak performance when it really matters. Training camps are helpful for all, but the quarterbacks and wide receivers especially benefit from these countless hours of practice. Here, it’s all about timing and chemistry.

The two go hand-in-hand. Good timing allows for those precision passes that we all marvel at, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, wondering how such a play is humanly possible. Good timing means good chemistry (a relationship, not the science) between the quarterback and the receiver. The quarterback will know exactly when to throw the ball and where to throw it because the two of them have practiced running the route, tossing the pigskin, making the catch in stride, and so on over and over and over to ensure maximum execution on game day. Practice makes perfect.

Are you still with me? So, how does any of this have anything to do with a Civil War battle?

One of my favorite things to look at when viewing battles and armies from over 150 years ago is to look at relationships–relationships between commanders and the relationships between commanders and the soldiers serving under them. How well did an army commander know and work with his corps commanders? How many battles had they served in together in their respective capacities? Did the soldiers trust their commanders, and did the commanders trust their soldiers? Was there any chemistry between them, and how did that affect their performance on the battlefield? To demonstrate, let’s return to another one of my favorite things to follow, the Maryland Campaign.

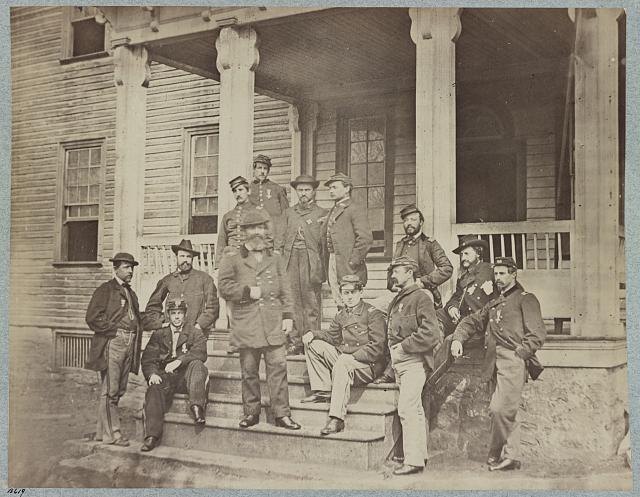

A while ago, I compiled some sabermetrics (baseball, anyone?) about the Army of the Potomac’s commanders from brigade level up to army command. I have charts breaking down prior military experience, West Point trained or not, how long they have commanded at the level they do at Antietam, and so on. From this statistical viewpoint, Edwin Sumner’s 2nd Corps was the Army of the Potomac’s best. It’s within that corps’ experience in the campaign that you can see how my wild football analogy comes back to the Civil War.

By September 17, John Sedgwick commanded the division under him at Antietam for 210 days. Together, he and his men used this time to train, gain experience, and become one of the best and most confident divisions in the army.

The division’s success caught the eyes of many, and army high command eyed Sedgwick for command of the 12th Corps early in the Maryland Campaign. Sedgwick, however, declined the offer, feeling “that he could do better service with the troops which he knew and which knew him” (emphasis added). That’s the army’s version of chemistry.

Despite the experience of Sedgwick’s division, there were some newcomers to the “team.” When Sedgwick’s command entered the West Woods on the Antietam battlefield and found itself caught in a very bad situation, Oliver Otis Howard had only been in charge of his Pennsylvania brigade for 21 days, and this was his first chance to lead it in a fight. Corps commander Edwin Sumner attempted to tell Howard to change the facing of his men so as to stem the Confederates surging towards the weak point of his line. Howard tried his best, but confusion reigned. The Pennsylvanians did good work in their chaotic situation. They slowed the Confederate attack, but could not stop it.

The maneuver of the Pennsylvanians was not flawless, however. In 1884, Howard wrote: “I think, even then, I could have executed such an order with troops which, like my old brigade, had been some time commanded by myself, and thoroughly drilled; but here, quicker than I can write the words, the men faced about and took the back track in some disorder, but not at first very fast” (emphasis added).

His brigade did fight well, but the implication is clear. If Howard had more time to familiarize himself with his regiments and their officers, it could have fought more effectively.

While comparing a game of football to the battlefield of any war is not a perfect analogy, the comparisons and importance of chemistry have always resounded loudly with me when I look at the ebb and flow of battle lines across a landscape. Fighting a battle with the fate of your country on the line and trying to score the game-winning touchdown with seconds left on the clock each do benefit tremendously from having good chemistry from top to bottom. Lacking that can leave an army, or a football team, on the wrong side of an outcome.

Nowhere is this more evident than in First Bull Run! Union commanders were only on page 5 of “the book” and barely knew where their encampments were.Confederate commanders were only a little bit better. Soldiers on both sides were depending on little more than luck and bravado, as they had only been soldiers for a few weeks.

It seems apropos to look at this now, on the 100th anniversary of the US’ entry into WWI. Thayer’s concept of the Military Academy was to create a “habit of thought” in officers, the idea being that the individual was unimportant as each was replaceable with no change in how the system would operate. The problem of course was that the standing (regular) army was way too small to ensure a critical mass of officers had that background in a major mobilization.

Experience made it clear that rapid expansion in wartime was horribly inefficient/ineffective. Thus beginning with the reforms of Root and extending through the National Defense Act of 1916 the army was transformed. The proof of concept would come in 1917.

Something else that may be worth looking at is the change of Marines from “sailors-with-guns” into a true “Marine Corps”.