The Turkish Grant

(Library of Congress)

Emerging Civil War welcomes back Frank Jastrzembski

In May 1897, the eminent Major General Nelson A. Miles departed from the United States to observe the Greek and Ottoman armies at war. The 57-year-old Miles was almost boyish in his enthusiasm to travel abroad. During the American Civil War, Miles rose from a lieutenant to the rank of major general by the age of 26-years-old, suffering at least three wounds in battle and fighting in most of the Army of the Potomac’s fiercest battles– He earned the Medal of Honor for his exploits at Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. Miles received the official consent from President McKinley, addressed in a letter from Secretary of War Russell A. Alger. The order permitted him to tour both the Ottoman and Greek armies to better understand their military operations, organization, equipment, arms and tactics.

With one aide-de-camp and clerk, Miles hurried to the Greco-Turkish front. He took a ship to London, and then on to Paris. He arrived to Constantinople on May 14 and was met by the acting American minister and ex-Confederate general, Alexander W. Terrell. Regrettably, Miles’ trip was cut short when he received an order from Washington to report back to London by June 15. Most of his observations related to the Ottoman Army would be made while quartered in the vicinity of Constantinople.

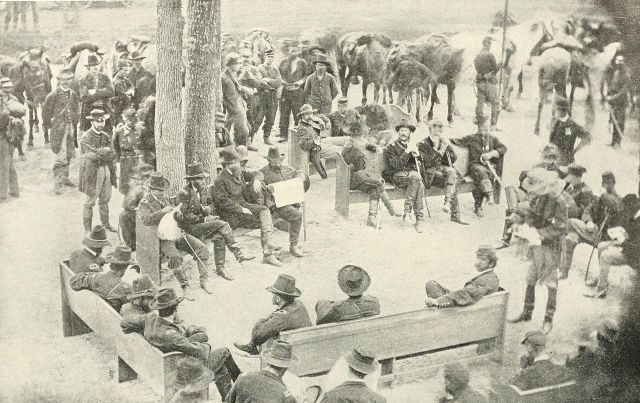

With the blessing of Sultan Abdülhamid II, he toured portions of the 30,000 Ottoman soldiers garrisoned in and around the Ottoman capital before departing on May 25. Even though he was unable to spend any quality time on the Greco-Turkish War front, he took much away about the Ottoman Army during his short tenure in Constantinople. Miles was much impressed by the regular Ottoman soldiers, applauding them for their temperance, faith, perseverance and flexibility to be molded into enduring soldiers – He even went far as to conclude they were “among the most effective in the world.” The Ottoman Army, to Miles, was “completely modernized” and no longer “antiqued” as many experts still believed, accrediting the labors of leased German officers who imposed strict discipline, well-structured organization, and ceaseless training on the regular soldiers following the Russo-Turkish War.

Of all the military men Miles met in Constantinople, and on his travels in Europe, he was most impressed with the 66-year-old Osman Nuri Pasha, commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Army. Miles described Osman as “a man about sixty-six years old, well built, of medium height, strong in physique, and intellectually the peer of any of the field-marshals that I subsequently met in Europe.” Osman graduated from the military academy of Constantinople in 1853, seeing extensive service during the Crimean War, where he netted a solid reputation for his aptitude for command and bold tactics.

Osman is best remembered in history for his tenacious defense of the village of Plevna during the Russo-Turkish War. Miles considered this siege as “one of the most brilliant defensive campaigns of modern times,” validating Osman’s “skill and tenacity” as a general. Osman stalled the Russian offensive for 143 days during the grisly siege, tying up over 100,000 Russian and Romanian soldiers and hundreds of guns from moving south toward Constantinople. His stubborn defense inflicted tens of thousands of casualties on the Russians. With dwindling provisions and pressure from daily bombardments, Osman attempted to break out of the Russian siege by early December with his 50,000 defenders, but it failed, leading to his capitulation.

To Miles, this Muslim general’s stature, manner, and dialogue emulated one his old superiors from his American Civil War days – the unforgettable Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant. Miles explained that, “Osman Pasha reminded me of General Grant more than any other man I saw on that side of the Atlantic. His manner is very much like that of Grant; man of few words – in these expressing condensed thought.” During the siege of Plevna in 1877, the taciturn Osman was found strolling along the trenches wearing a soiled federal blue jacket that reached down to his knees, unadorned with any rank or insignia – Much like Grant during his Overland Campaign, but without the cigar dangling from his lips. Osman shared with Miles a proverb that he lived by, one that likewise propelled Grant to his greatest victories and got him through the lowest points of his army career: “Persistency is the great secret of success in war. If an army is not successful one day, tenacity of purpose and persistency will in the end bring victory.”

The champion of Plevna would die on April 5, 1900, only three years after meeting Miles. Upon his return to the United States, General Miles recorded this meeting with this Ulysses S. Grant-styled Ottoman general in his official report. Miles’s observations exposed an interesting component. Despite distinct religious and cultural differences between Grant and Osman, both shared the same methodology for obtaining success in war. Tenacity of purpose and persistency on the battlefield not only helped Grant to prevail throughout the American Civil War from 1861-1865, but it also did the same for Osman nearly a decade later and roughly 5,000 miles away in Bulgaria in 1877.

Further Reading

Jastrzembski, Frank. Valentine Baker’s Heroic Stand at Tashkessen 1877: A Tarnished British Soldier’s Glorious Victory. Barnsley: Pen &Sword Books, 2017.

Miles, Nelson A. Military Europe: A Narrative of Personal Observation and Personal Experience. New York: Doubleday and McClure Co., 1898.

Miles, Nelson A. Report of Major General Nelson A. Miles, Commanding U.S. Army, of His Tour of Observation in Europe: May 5 to October 10, 1897. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899.

Great article. Here is a Civil War irony. There were foreign military observers at the Battle of Cold Harbor and the 1864 Petersburg Campaign. These officers saw what trench warfare could do, and the high casualties suffered by attacking entrenched positions. The reports they wrote must have been ignored and filed away. Trench warfare in World War I started approximately 50 years to the day after Cold Harbor

I write this reply because there is no “Like” button or something to that effect.

Excellent piece. Thank you.

Thank you! As you can tell, I am a Russo-Turkish War junkie.

That series of wars have so many stories, actually. It is a shame that the academias of both sides (Turkish and Russian) do not put enough attention there.

Thank you for your care. I’m looking forward to reading your new articles.