“No Time for Dallying”: “Grumble” Jones and the Battle of Brandy Station

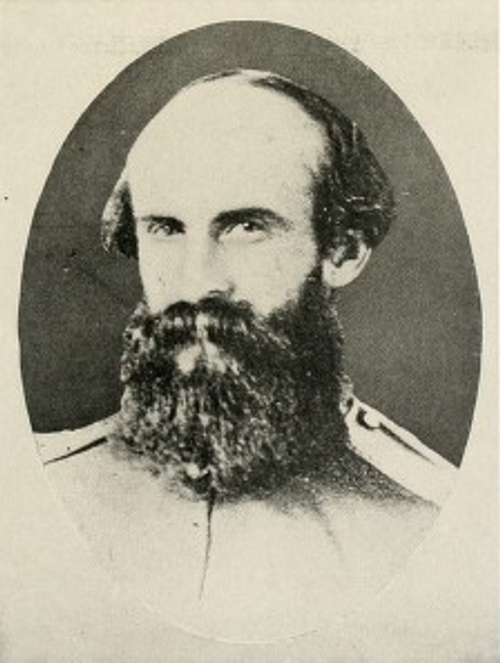

Next weekend marks the Fourth Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium. Each year to close out the activities, we have conducted a tour on Sunday of a battlefield which fits the scope of the weekend’s theme. This year, attendees will explore Brandy Station. A prominent character in the battle’s story is Brig. Gen. William E. “Grumble” Jones, a man J.E.B. Stuart described as the “best outpost officer in the army”.

Jones was a Virginian and had attended Emory and Henry College prior to entering West Point. He graduated in the Class of 1848. Jones received a commission in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles and served in the Pacific Northwest. He resigned in 1857 to take up farming near Glade Spring Depot, Virginia.

When war broke out, Jones raised a cavalry company and later commanded the 1st Virginia Cavalry. He headed the 7th Virginia Cavalry prior to his promotion to Brigadier General in September, 1862. In November, he took over a brigade of Virginia horsemen formerly led by Turner Ashby. Despite his rise, Jones was irritable and difficult to get along with. His disposition stemmed from the loss of his wife in the antebellum years.

In the first week of June 1863, Jones joined the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry division northeast of Culpeper Courthouse. Gen. Robert E. Lee was planning his second Northern invasion and had ordered Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart to concentrate west of Fredericksburg. Jones’ brigade, which consisted of the Sixth, Seventh, Eleventh, and Twelfth Regiments, along with the Thirty-Fifth Battalion, camped along the Beverly Ford Road near a stop on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad known as Brandy Station. He had orders to cross the Rappahannock on the morning of June 9 and begin the process of screening the infantry march.

Unbeknownst to Jones and the Confederates, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s Union cavalry lurked on the north bank. Stuart’s presence had not gone unnoticed by the Federals. Alarmed by the possibility that Stuart intended to launch a raid into his rear, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac, directed Pleasonton to initiate an expedition of his own and destroy the Confederates.

Around 4:30 a.m. on June 9, 1863, Pleasonton’s Right Wing under Brig. Gen. John Buford, a former West Point classmate of Jones, splashed over Beverly’s Ford. Colonel Benjamin “Grimes” Davis’ brigade led the advance. Although surprised and outnumbered, elements from the 6th Virginia under Bruce Gibson and Cabel Flournoy put up a stubborn resistance. During the ensuing fight, Davis was killed by an officer from the 6th Virginia, Robert Allen. By now, the sound of gunfire and frantic couriers had alerted Jones and the Confederate cavalry to the threat. “There was no time for dallying” wrote the historian of Jones’ brigade. Riding to the aid of their comrades was Lt. Col. Thomas Marshall’s 7th Virginia. Collectively, the fighting by Jones’ regiments brought the enemy column to a halt, secured Maj. Robert Beckham’s horse artillery camped nearby and gave Stuart an opportunity to reform on a ridge occupied by St. James Church. Jones occupied the center of the line. Brig. Gen. William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee took up position on Jones’ left while Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton held the right.

To get a sense of what stood in front of him, Buford decided to send the 6th Pennsylvania to probe Stuart’s line. The Pennsylvanians charged valiantly into the teeth of Beckham’s guns, supported by the 35th Virginia Battalion. Positioned above St. James Church, the 12th Virginia also joined the fight, launching an attack into the flank of the 6th Pennsylvania and engaging the 6th U.S. Cavalry which had moved forward to support the Keystone Staters. Stuart’s line held and the two sides were content to engage in long range skirmishing in the St. James Church sector for the next several hours.

Late in the morning, a new threat developed in Stuart’s rear. Pleasonton’s Left Wing under Brig. Gen. David Gregg had crossed the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and had made their way to Brandy Station to link up with Buford. Gregg’s arrival presented a serious threat to Stuart’s position. If Gregg could take and hold Fleetwood Hill, a long ridge that rose up from Brandy Station, Stuart would be trapped between the two Union commands.

Cautiously, Stuart began to pull regiments from St. James Church to contend with Gregg. The 12th Virginia and the 35th Virginia Battalion opened the struggle for Fleetwood Hill when they encountered Federals under Col. Percy Wyndham at the crest. The fighting escalated as more gray regiments reached the scene. Joining in the Union attack was a section of Capt. Joseph Martin’s 6th New York Independent Battery, which unlimbered at the base of the hill along Flat Run. Martin soon attracted the attention of the Confederates. Several charges by the 6th Virginia and 35th Virginia Battalion inflicted severe casualties on the artillerists and eventually the guns were out of action. Fortunately, Stuart’s troopers were able to hold on to Fleetwood Hill.

Late in the afternoon, Pleasonton, who had come across the river to observe the battle, elected to disengage and withdraw. Despite the day long drubbing at the hands of Pleasonton, Stuart remained in control of the field. Much of Stuart’s success was in part due to the efforts of his subordinates. Jones’ brigade was heavily involved in the morning and afternoon stages of the engagement on the northern end of the field. Throughout the battle, his troopers helped repulse attacks on the Beverly Ford Road, at St. James Church and atop Fleetwood Hill. As can so often be the case, Jones’ contributions have overshadowed those of his brother officers. Rooney Lee, for instance, waged a desperate fight against Buford on the farm of Richard Cunningham and again on Yew Ridge. Like Lee, Jones’ actions would soon be forgotten, especially in the eyes of his commander.

Jones’ ill-temperament and prickly disposition had alienated a number of those around him, particularly Jeb Stuart. Although Stuart thought highly of Jones’ skill, the two clashed on a personal level. Later in 1863, following a dispute with Stuart, Jones was transferred to command the Department of Southwest Virginia and East Tennessee. In this capacity, Jones supported James Longstreet Knoxville efforts and fought at Cloyd’s Mountain. Almost a year to the day after Brandy Station, Jones was killed at the Battle of Piedmont. He rests today in the cemetery of Old Glade Spring Presbyterian Church in Washington County, Virginia.

Jones was posted to the Northwest (Oregon) after he left West Point. After a short period he was posted to Texas. After a period, he went on leave to return home to married his fiancee. Traveling by ship back to Texas, she was washed overboard and drown. No wonder he was he was known to “Grumble”,

Yes and it appears he never recovered from it.

Cavalry actions are always an enjoyable read !

Thanks, David!

I enjoyed your article. I know some about Jones from reading about Gettysburg and the Battle of Fairfield on July 3, and about the fighting that occurred during the Confederate retreat from Gettysburg. You provided a nice primer for me for the Brandy Station tour.

Thanks, Rob!

I feel like Jones’ wife death is over connected to his nickname Grumble and his ability to interact with others. No doubt it affected him deeply, but I discount its lasting effects on his interactions with others. He rose to become a general and that wouldn’t have happened if he was some angry wreck of a man.

Stuart seems to have been judgmental of Jones’ lack of a cavalier style and differences in personality, which led to Jones’ being offended and causing dislike between the two. That said, Stuart somehow got along with Stonewall Jackson, who was notoriously plain and ornery but who did make an early name of himself, which I suspect supports Stuart admiring Jackson.

We are missing so much information about these peoples’ personalities and relationships.

I think Eliza Jones’ death had a lasting impact on her husband. One individual wrote after the war that the event left Jones with a “sad and broken heart”. A relatively recent biographer of Jones states that his life “was changed forever” after her death. Jones may have also carried a strong sense of guilt. While he was unable to save her during the wreck, one of his cousins managed to rescue him.

Although the two men possessed markedly different personalities, it seems that Stuart and Jones got along very well in the early stages of the war. By the spring of 1862, the relationship had taken a downward turn, although the circumstances surrounding the collapse are unclear. The animosity between the two men likely dates from April 1862 when Jones was Colonel of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. There is still some question as to the exact events, but Stuart managed to supplant Jones with the regiment’s Lieutenant Colonel and a personal favorite of his, Fitzhugh Lee. Jones vehemently protested to the Secretary of War and the Confederate War Department transferred him to command of the 7th Virginia Cavalry.

Following Jones’ promotion to Brigadier General, Stuart wrote directly to the War Department informing them that he was unfit for command. When Jones was assigned to Stuart’s cavalry division, Stuart requested that Robert E. Lee transfer Jones to the infantry. Lee deferred the decision to Jones. Jones responded by tendering his resignation which Secretary of War James Seddon refused to act on.

Following the Gettysburg Campaign, Stuart finally took action himself and relieved Jones of command for his actions at Monterey Pass. Stuart contended that Jones had failed to protect Richard Ewell’s wagon train. Jones responded by personally attacking Stuart in a scathing letter for which Stuart placed him under arrest and preferred three charges against him: disobedience of orders, conduct prejudicial to military order and discipline and behavior with disrespect to his commanding officer. A subsequent Court Martial found Jones guilty of only the last charge and he was transferred out of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Yep, I’ve read all this. This is just the Jones-Stuart conflict. IIRC, there are Confederates are on record admiring Jones in some ways. I also have the impression that Lee and Stonewall Jackson liked Jones.

And if someone wants to suggest that Jones suffered from depression, I think I would believe it. What depression he had didn’t stop him from commanding cavalry. If he was really mentally debilitated he wouldn’t have even served.

Wade Hampton is another example of someone Stuart didn’t like. Stuart had prejudices.

Oh yes! Beverly Robertson is also in that category.

Yep, Beverly Robertson too.

Robertson, however, wasn’t seen as a competent field officer, whereas Jones and Hampton were (by others or even Stuart). D.H. Hill, for example, from there time together in North Carolina, thought Robertson was a poor field officer.