A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 1

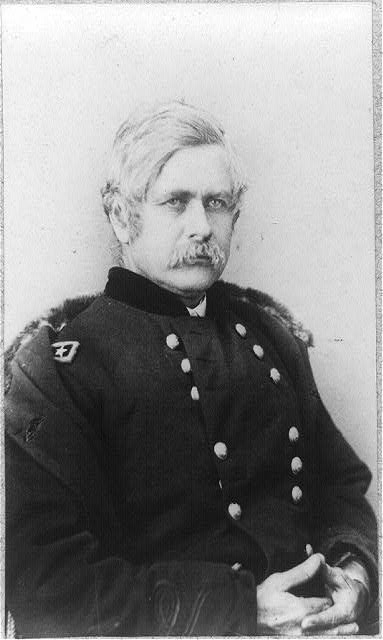

In March 1865, a conference was planned where the leading officers on both sides—and their wives—would have played a significant role in brokering peace. It was Maj. General Edward O.C. Ord’s idea, proposed in the wake of the failure of the Hampton Roads peace conference on February 3rd. He had a plan to bring Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee together in a military convention to do what the politicians of the time were unable to do, that is, find a path to peace. His plan also had a surprising twist. He wanted to bring old friends Julia Dent Grant and Maria Louisa (“Louise”) Longstreet together for a cordial reunion that could become a model for friends and families long divided by war. It was a remarkable idea for its time.

Although the proposed conference never materialized, the plans surrounding it help us to better understand the critical period shortly before the surrender of the Confederate armies that led to the end of the Civil War. Falling between the Hampton Roads negotiations and Appomattox, it illuminates the role of military leaders on both sides who saw an opportunity where politicians had failed to try and end the conflict without having to engage in any more bloodshed. By opening up channels of communication between old friends, simply talking to one another, these military leaders, namely Union General Edward O. C. Ord and Confederate General James Longstreet, thought they could pave the way for Generals Grant and Lee to open peace negotiations in a military convention. Then, when the fighting had stopped, the political leaders could iron out the terms for restoring the Union.

What especially made this proposed peace conference different from the ones that preceded it was the inclusion of the officers’ wives in the reunion process. It was a visionary idea that would have empowered women, recognizing their significant role in fighting the war on the homefront, and acknowledging their participation in reconstruction. The women would have become important cultural symbols of reconciliation, setting the stage for friends and families long divided by war, and perhaps alleviating some of the bitterness engendered after four tragic years of sacrifice and loss.

In the end, the proposed peace plan also creates an interesting counterfactual narrative. It is intriguing to think what would have happened if the plan had been carried out as Ord and Longstreet had imagined. Could they have successfully opened the road to peace where others had failed, and ultimately saved lives from a cessation of hostilities in the process? Unfortunately, we will never know what would have resulted from this creative proposal. But the plan itself provides a window into the extraordinary dynamics behind Union and Confederates lines in the waning days of the war.

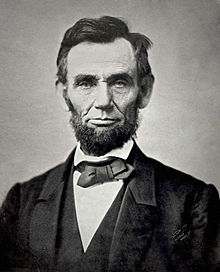

The roots of the March conference grew out of the failure of the meeting at Hampton Roads, Virginia, where three Confederate commissioners—Vice President Alexander Stephens, former Supreme Court Justice John Archibald Campbell, and Senator Robert M.T. Hunter—met with President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward on board the steamer River Queen near Fortress Monroe. The commissioners were hoping to negotiate for a cessation of hostilities and ultimately southern independence, which was essentially a nonstarter for Lincoln. At no point during the war was he willing to recognize the Confederacy as a legitimate nation, let alone entertain the idea of a permanent division of the Union into two separate countries, as Confederate President Jefferson Davis had called for when he approved the peace mission. From the beginning of the war, Lincoln had argued that preserving the Union was his primary concern; four years later, he was not about to give up on that goal. To that end, restoring the Union—one and indivisible—was Lincoln’s ultimate objective.[1]

By the winter of 1865, the situation in the Confederacy was becoming desperate. Civilians and soldiers alike were having difficulty procuring needed supplies; meanwhile, prices for goods were skyrocketing while Confederate currency values were plummeting. Desertions were on the rise as desperate families called on soldiers to come home immediately, and there simply were not enough men to refill the ranks. It was increasingly becoming evident that the fall of the Confederacy was only a matter of time. In a report to Secretary Breckinridge, for example, Lee warned that “it must be apparent to every one” that the condition of the military was “full of peril and requires prompt action.” The fear, however, in the North, was that the Confederate army might disband and fight on, engaging in guerilla warfare. The war would then drag on indefinitely, imperiling any attempts to restore the Union.[2]

The arrival of the commissioners at Hampton Roads, who referred to themselves as “informal agents,” inspired great hope among both Union and Confederate soldiers. “When they came within our lines,” General George Meade wrote his wife, “our men cheered loudly, and the soldiers on both sides cried out lustily, ‘Peace! Peace!’” To this end, while negotiations were underway, Stephens suggested that a military convention could help to facilitate peace since it “could be made to embrace, not only a suspension of actual hostilities… but also other matters” as well. Campbell recounted that “the objections entertained by Mr. Lincoln to treating with the Government of the Confederacy, or with any separate State, might be avoided” if they were to pursue this course, bringing together “the commanding generals of the armies of the two belligerents” in a face-to-face meeting rather than “the usual mode of negotiating through commissioners or other diplomatic agents.” Lincoln, however, rejected the idea, and “repeated his determination to do nothing which would suspend military operations, unless it was first agreed that the National Authority was to be re-established throughout the country.” The negotiators had reached an impasse; the war would continue.[3]

To be continued…

[1] For more information on the Hampton Roads peace conference, see James B. Conroy, Our One Common Country: Abraham Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference of 1865 (Guilford, CT, 2014). See also Richard Striner, “Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Conference,” 1865: America Makes War and Peace in Lincoln’s Final Year, ed., Harold Holzer and Sara Vaughn Gabbard (Carbondale, 2015), 40-51; William C. Harris, “The Hampton Roads Peace Conference: A Final Test of Lincoln’s Presidential Leadership,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, vol. 21 (Winter 2000): 30-61; Charles W. Sanders, Jr., “Jefferson Davis and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference: ‘To Secure Peace to the Two Countries,” Journal of Southern History, vol. 63, no. 4 (November 1997): 803-826.

[2] Robert E. Lee to John C. Breckinridge, March 9, 1865, Clifford Dowdey and Louis H. Manarin, eds., The Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee. (New York, 1961), 911.

[3] George Meade to Mrs. George G. (Margaretta Sergeant) Meade, February 1, 1865, The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, vol. II (New York, 1913), 260; Alexander H. Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States: Its Causes, Character, Conduct and Results, vol. II (Philadelphia, 1870), 607; John A. Campbell, Reminiscences and Documents Relating to the Civil War During the Year 1865 (Baltimore, 1887), 51-52; Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, 609.

Gee, if only they’d thought of this before they went to war. A teaching moment? If history is any example, apparently not. And here we are perhaps on the brink of another conflagration.

Great article, Dr. Schulte. Good to have you aboard ECW!