A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 2

While many were disheartened by the failure of the February conference, the Confederates were not willing to give up their hope of establishing an independent nation, although that hope was becoming dimmer with each passing day. So before they left Hampton Roads, the commissioners tried to leave a door open for future negotiations, asking Lincoln to reconsider the possibility of a military convention. Campbell recalled that Lincoln agreed to reevaluate the plan, but admitted that he had already “maturely considered” this idea, “and had determined that it could not be done.” Still, holding on to a slim reed of hope, Campbell acknowledged that the March conference “was supposed to be in consequence” of this earlier suggestion.[1]

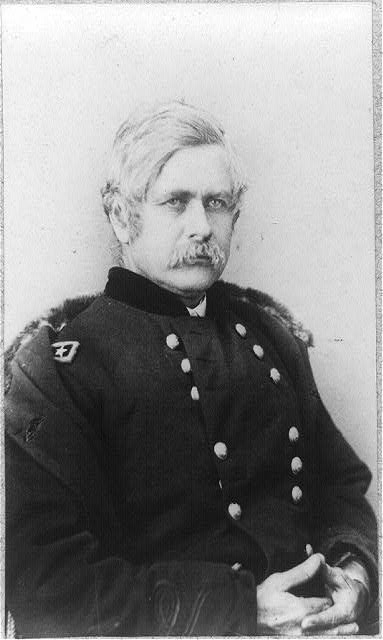

General Ord had a plan, however—with a twist. If the politicians could not end the war, perhaps the officers—and their wives—could. Despite the fact that Lincoln had already rejected this idea (albeit without the wives), Ord had a slightly different approach. He hoped the officers could initiate a military convention without political interference. The Hampton Roads commissioners had suggested as much to General Meade before their conference, admitting how “they thought it a pity this matter could not be left to the generals on each side, and taken out of the hands of politicians.” Meade agreed. “I had no doubt a settlement would be more speedily attained this way,” he said.

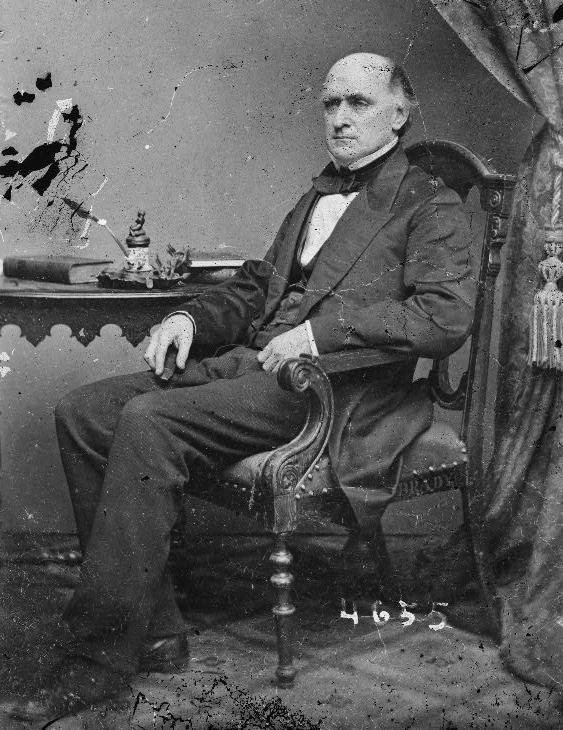

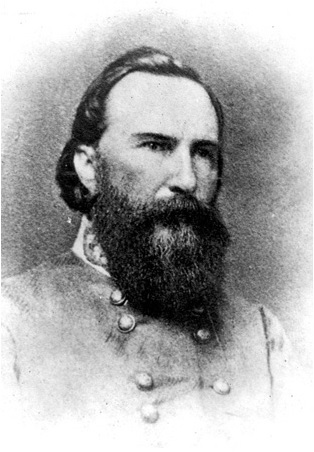

The commissioners also spoke with Ord as they were leaving Hampton Roads, and as Bernarr Cresap points out, it would be “reasonable to assume” that the subject may have come up again. For it was only a few weeks later when Ord, who had recently assumed command of the Army of the James, reached out to an old friend on the Confederate side, Lt. General James Longstreet, General Lee’s second in command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Ord and Longstreet could trace their friendship, like so many officers on both sides, to their West Point days. But rather than directly introducing his idea to facilitate peace, Ord instead sent Longstreet a letter requesting an interview to discuss how to end the friendly exchanges of tobacco and coffee, among other things, that were occurring between the soldiers across the lines. Using the pretext of ending fraternization among the soldiers was ironic since Ord was about to propose a plan that encouraged fraternization among the leading officers. In any event, Longstreet suspected that Ord had something else in mind since he could have easily stopped the exchanges without his help. He agreed to the meeting.[2]

In his memoirs, Longstreet described this encounter:

General Ord, commanding the Army of the James, sent me a note on the 20th of February to say that the bartering between our troops on the picket lines was irregular; that he would be pleased to meet me and arrange to put a stop to such intimate intercourse. As a soldier he knew his orders would stop the business; it was evident, therefore, that there was other matter he would introduce when the meeting could be had. I wrote in reply, appointing a time and place between our lines.

We met the next day, and presently he asked for a side interview. When he spoke of the purpose of the meeting, I mentioned a simple manner of correcting the matter, which he accepted without objection or amendment. Then he spoke of affairs military and political.[3]

After quickly resolving the bartering problem, the two men moved on to the real purpose for their meeting. Ord proposed that since the politicians could not—or would not—successfully negotiate for peace, perhaps they should bring Grant and Lee together, and maybe they could become the arbitrators of peace. But that was just the beginning, for while this idea had been talked about on both sides for awhile, Ord added his own unique personal touch, proposing a separate meeting for women, specifically, Grant’s wife, Julia, and Longstreet’s wife, Louise. Thus, while the men were negotiating an end to the hostilities, the women could act as cultural symbols of reunion, thus beginning the process of reconciliation. Longstreet described Ord’s idea:

Referring to the recent conference of the Confederates with President Lincoln at Hampton Roads, he said that the politicians of the North were afraid to touch the question of peace, and there was no way to open the subject except through officers of the armies. On his side they thought the war had gone on long enough; that we should come together as former comrades and friends and talk a little. He suggested that the work as belligerents should be suspended; that General Grant and General Lee should meet and have a talk; that my wife, who was an old acquaintance and friend of Mrs. Grant in their girlhood days, should go into the Union lines and visit Mrs. Grant with as many Confederate officers as might choose to be with her. Then Mrs. Grant would return the call under escort of Union officers and visit Richmond; that while General Lee and General Grant were arranging for better feeling between the armies, they could be aided by intercourse between the ladies and officers until terms honorable to both sides could be found.[4]

Ord’s plan was remarkable for the inclusion of women. In the antebellum era, middle class Americans, particularly in the North, had constructed separate spheres for men and women that mirrored the separation of home and work as the economy was undergoing significant transformations because of rising industrialization. Thus, men’s roles were increasingly defined by “public” activities, while women were relegated to a “private,” domestic realm. The proposed dual interviews fell clearly inside this ideological framework, yet at the same time challenged it, by providing women with a semblance of power in their public role as mediums of peace within this nonthreatening domestic environment.

Focusing specifically on officers’ wives, and paralleling the generals’ discussions, the inclusion of women in the negotiations on a corresponding track would have highlighted the broader impact of the conflict. Women fought the war on the homefront. They had to contend with sacrifice and loss, shortages and sickness. Some even had to protect their families and property when their farms became battlefields, or the armies sought to requisition supplies. Others nursed wounded soldiers when their homes became hospitals. Granted, as the wives of the leading officers, Julia Dent Grant and Louise Longstreet were in a much more privileged position than the average soldier’s wife. But they, too, were no strangers to sacrifice and loss, and the subsequent pain and anxiety that followed. Louise Longstreet, for example, not only lost family members in the war, but also suffered the tragic loss of three of her four children within a week when a scarlet fever epidemic ravaged Richmond in January 1862. She almost lost her husband as well when he was severely wounded at the Wilderness in May 1864. Julia Grant also experienced the pain of losing loved ones in the war.

Now in this proposed women’s meeting, old friends Julia Grant and Louise Longstreet would come together as friendly symbols of peace and reunion while their husbands discussed ways to end the war. Lt. Colonel Horace Porter, who served on Grant’s staff, noted how “it was taken for granted that the natural chivalry of the soldiers would assure such cordial and enthusiastic greetings to these ladies that it would arouse a general sentiment of good will, which would everywhere lead to demonstrations in favor of peace between the two sections of the country.” Believing erroneously that Longstreet was the author of the plan, Porter declared this to be “an interesting but rather fanciful program,” one that was “so visionary that it seems strange that it could ever have been seriously discussed by any one.”[5]

To be continued…

[1] Campbell, Reminiscences and Documents Relating to the Civil War During the Year 1865, 51-52.

[2] George Meade to Mrs. George G. Meade, February 1, 1865, The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, vol. II, 259; Bernarr Cresap, Appomattox Commander: The Story of General E.O.C. Ord (San Diego, 1981), 162-163.

[3] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox (1895; New York, 1992), 583-584. Based on contemporary records, the date of the first meeting was most likely February 25, not the 21st, as Longstreet recalled. See Donald Bridgman Sanger and Thomas Robson Hay, James Longstreet: I. Soldier, II. Politician, Officeholder, and Writer (Baton Rouge, 1952), 288.

[4] Ibid., 584.

[5] Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (1897; Lincoln, 2000), 391-392.

1 Response to A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 2