“A Tremendous Little Man” – Newton Schleich in the Civil War

(MOLLUS)

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Jon-Erik Gilot

Generally speaking, political generals during the Civil War were a mixed bag. Some would thrive in the military hierarchy while others could make life hard on their superiors as well as the men serving under them. In a war fought largely by amateur soldiers, politically appointed generals were amateurs themselves, which often lead to disastrous results for armies North and South. In this article I’d like to introduce you to Newton W. Schleich, ranking as arguably one of the worst political generals produced by the state of Ohio during the Civil War.

Schleich was born in Lancaster, Fairfield County, Ohio in 1827. As a young man, he studied law under William Medill, a strong Ohio Democrat who would hold positions in several presidential administrations and rise to Governor in 1853. Schleich was admitted to the Ohio Bar in 1850 and made a name for himself as a capable barrister. In the mid-1850’s, he also served as editor of the Ohio Eagle newspaper, a controversial Democratic paper owned by Charles and John Brough, who would govern Ohio during the final years of the Civil War.

Newton Schleich was a well-known face around Lancaster. In addition to his law and newspaper business, he served as an officer of the Fairfield County Agricultural Society, was active in the local railroad, and in 1853, was named captain of the City Guards, a local militia company. In 1857, “Colonel’ Schleich” (as he was advertised on voter returns) was elected to represent the twelfth district in the Ohio Senate and was reelected to a second term in 1859. He campaigned for Stephen Douglas in the 1860 presidential election, but pledged his support to the Union during the secession crisis, urging for “the Democracy to join hands with the Republicans in efforts to restore peace and maintain the Union.”[i] On the eve of the 1880 Republican Convention, Senator James A. Garfield would recollect his earlier days in the Ohio Senate, recalling that it was Senator Schleich, who “with all the look of anxiety and agony in his face,”[ii] delivered word to the senate chamber of the firing on Fort Sumter.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Schleich had made a name for himself as drillmaster of the Ohio militia’s legislative squad, which drilled on the statehouse steps in Columbus. Given this experience and political stature, Schleich had positioned himself to receive a military appointment at the outbreak of the war. He continued in his legislative duties until April 1861, when he offered his services to Governor William Dennison, who appointed Schleich as a Brigadier General in the Ohio Militia.

At Schleich’s urging, on May 1, 1861, Ohio’s Adjutant General Henry Carrington established Camp Anderson at the Fairfield County Fairgrounds in Lancaster, which would serve as the training camp for the newly-formed 17th Ohio Infantry. Carrington tasked Schleich with securing contracts for the subsistence of the troops stationed in Lancaster. Schleich was immediately accused of showing favoritism in the granting of contracts for rations and supplies by accepting higher bids from friends and colleagues. With interest in the railroad which would convey the troops and in the fairgrounds where they were quartered and with the power to grant favorable contracts to friends, Schleich had mastered pork barrel politics.

The following month Schleich moved to western Virginia to take charge of a brigade under Major General George B. McClellan, commanding general of the Department of the Ohio. McClellan didn’t think much of Schleich, admitting in a letter home to his wife that Schleich “knows nothing.”[iii] The men serving under him thought even less of their brigadier general. Lieutenant Colonel John Beatty of the 3rd Ohio pulled no punches when describing Schleich in his memoirs:

He is a three-months’ brigadier, and a rampant demagogue. Schleich said that slaves who accompanied their masters to the field, when captured, should be sent to Cuba and sold to pay the expenses of the war. Schleich was a State Senator when the war began. He is what might be called a tremendous little man, swears terribly, and imagines that he thereby shows his snap. Snap, in his opinion, is indispensable to a military man. If snap is the only thing a soldier needs, and profanity is snap, Schleich is a second Napoleon. This General Snap will go home, at the expiration of his three-months’ term, unregretted by officers and men.[iv]

Schleich’s abbreviated brigade contained only two regiments under his active command – the 3rd and 4th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. From their camp at Buckhannon, in Upshur County, Schleich authorized a July 5 expedition of fifty men from the 3rd Ohio to reconnoiter the Staunton & Parkersburg Turnpike. The Ohioans advanced as far as Middle Fork Bridge, where a brief but highly-publicized skirmish occurred less than ten miles from the Confederate main body entrenched at Rich Mountain. General McClellan was furious that Schleich authorized an expedition without his knowledge, thereby alerting the Confederates to McClellan’s movement and forcing him to advance on Rich Mountain before he was ready. After the war, R.C. Galbraith, chaplain of Schleich’s brigade and a serious Schleich apologist, published an article in The Ohio Soldier newspaper, stating his belief that Schleich’s misstep in the Middle Fork reconnaissance directly resulted in McClellan’s later rise to prominence. Galbraith would write that Schleich’s authorization of the mission “…precipitated the battle of Rich Mountain, made a ‘Young Napoleon’ out of McClellan, and gave him command of the Army of the Potomac,” though admitting that McClellan had delivered a “sharp reproof” for Schleich’s “carelessness.”[v]

McClellan had had enough of Newton Schleich and, by July 24, ordered Brigadier General Joseph J. Reynolds to replace Schleich in the Cheat Mountain District. A general without a command, Schleich was ordered back to Columbus where he resigned his commission on July 30, 1861.

By August 1861, Schleich was already hard at work seeking a full brigadier general appointment from Washington, D.C. When that appointment did not come through, he accepted a commission as colonel of the newly-minted 61st Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Back in Lancaster, Schleich established Camp Medill during the winter and spring of 1862. When the regiment was slow to organize, Governor Dennison looked to transfer several companies to another field-worthy regiment. Having spent more than $400.00 of his own money in raising the regiment, Schleich begged for the men to stay, and Dennison relented. The regiment was officially organized by the end of April 1862 and ordered to Western Virginia the following month.

Schleich was no more popular among the men of the 61st than he had been with his previous command. Robert Patterson, a Sergeant in Company F, wrote home in August 1862 that “if I had known before I came into the service that I was going to be under his [Schleich’s] command I should have given this regt a very wide berth.” [vi] While nepotism was commonplace among Civil War regiments and staffs, Patterson argued that Schleich took it too far, appointing relatives and friends to posts throughout the regiment ahead of more experienced officers with earlier commission dates. Patterson further argued that “it is very unpleasant to be commanded by a lot of men who know nothing and will learn nothing but whose sole merit is that they are Col Schleich’s brother-in-law or cousin.”

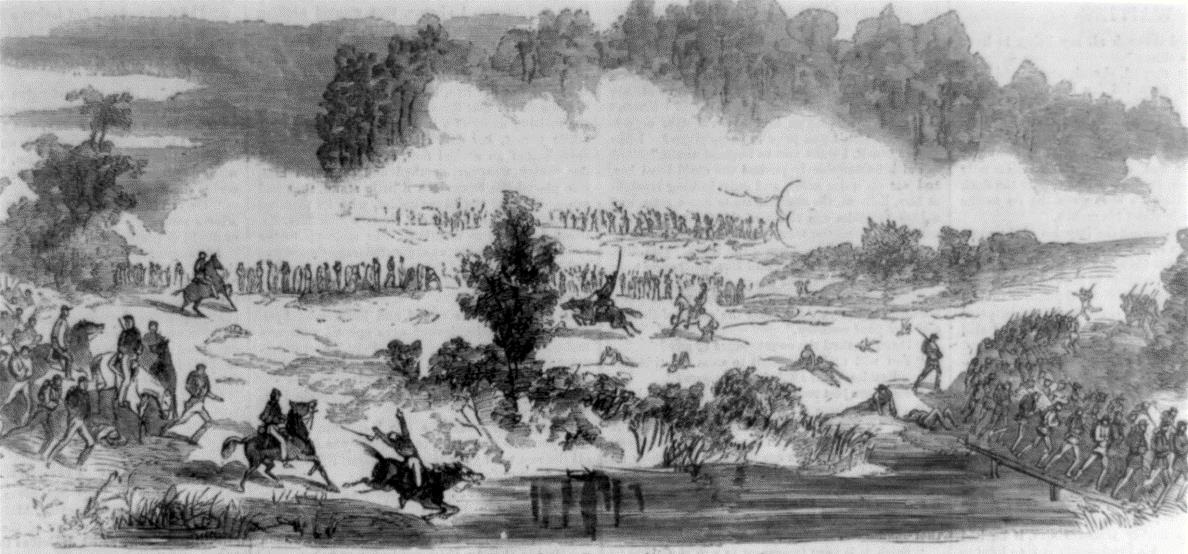

The 61st Ohio was attached to the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, 1st Corps of the Army of Virginia, arriving at Cedar Mountain, near Culpepper, Virginia, on the evening of August 9, 1862, after the vicious battle had come to a close. The regiment’s baptism of fire came less than two weeks later on August 22, 1862, at Freeman’s Ford on the Rappahannock River. Here, Brigadier General Henry Bohlen directed his undersized brigade across the river where they ran into three full Confederate brigades belonging to General James Longstreet. Outmanned with their backs to the river and with General Bohlen killed, the 61st fired two volleys before falling back across the river. “Our men ran down the hill and plunged into the river at whatever point they happened first to make – some swimming, others running the best way they could, and others trudging through the mud, the enemy’s balls falling in the river and on the opposite bank…like hail in a violent storm” recalled Private Joseph Lowe of Company C.[vii]

Over the following two days, the 61st engaged at Sulphur Springs and Waterloo Bridge before withdrawing to Warrenton, Virginia. During each engagement, Colonel Newton Schleich was notably absent from the regiment. In his official report of the engagements, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen J. McGroarty acknowledged that, while Schleich had accompanied the regiment across Freeman’s Ford, he soon afterwards could not to be found. McGroarty took command of the regiment for the remainder of the fight as well as the subsequent Rappahannock engagements while Schleich was still missing. Schleich did not surface until the evening of August 24, when he turned away a squad of men sent by Lieutenant McGroarty to bring up fresh beef that had been stored in several ambulances. Schleich chastised the Lieutenant in charge of the squad that “he should not take a God d-d bite of it unless the regiment marched back to get it.” [viii] McGroarty specifically name dSchleich and seven other commissioned officers of the 61st Ohio as “unaccountably absent.”

Rumors swirled – cowardice, drunkenness, negligence, desertion. General Alexander Schimmelfennig, who took command of the 1st Brigade following Bohlen’s death, cleaned house among commissioned officers in each regiment of the brigade following the fight at Freeman’s Ford. While others were relieved of command or sent to undesirable posts, Schleich saw a looming threat of court martial. With his old nemesis George McClellan back in command of the army, Schleich realized his days were numbered. On September 20, 1862, Newton Schleich tendered his resignation, which was approved by General McClellan just three days later. More than a dozen other commissioned officers in the 61st Ohio – many of them Schleich’s personal appointments – also resigned. Lieutenant Colonel Stephen McGroarty became the commander and led the regiment for the duration of the war.

(Chroniclingamerica.gov)

Schleich returned to Lancaster and quietly resumed his law practice. He advertised himself as a friend of the soldier, paying “especial attention to collections, bounty pension and back pay claims of soldiers and their friends.”[ix] Woefully aware of his dubious wartime record, Schleich was sometimes required to defend himself. At a September 1865 Democratic convention in Lancaster, he got into a physical confrontation with a man who had questioned Schleich’s military aspirations and patriotism. An account of the convention noted that “…as Schleich never did much fighting, no bones were broken.” [x] He carried the title of ‘General’ until his death on September 22, 1879, his obituary conveniently noting that Schleich commanded the 61st Ohio “until failing health required his resignation.” [xi]

Newton Schleich is buried at Forest Rose Cemetery in Lancaster, Ohio.

(Findagrave.com)

[i] The Weekly Lancaster Gazette (Lancaster, Ohio), 17 Jan. 1861. Chronicling America

[ii] The Wellington Enterprise (Wellington, Ohio), 29 Jan. 1880. Chronicling America

[iii] Sears, Stephen W. The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan. (New York: Da Capo Press). 1992. Pgs. 43 – 44

[iv] Beatty, John. The Citizen Soldier – The Memoirs of a Civil War Volunteer” (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press). 1998. Pg. 35

[v] The Ohio Soldier (Chillicothe, Ohio) 27 Aug. 1887

[vi] MS-236, Patterson Family Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio

[vii] The Circleville Democrat (Circleville, Ohio), 19 Sept. 1862

[viii] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Series 1 – Volume 12 (Part II). Pgs. 308 – 310

[ix] Lancaster Gazette (Lancaster, Ohio), 07 May 1863. Chronicling America

[x] The Lancaster Gazette (Lancaster, Ohio), 07 Sept 1865. Chronicling America

[xi] Lancaster Ohio Eagle (Lancaster, Ohio), 25 Sept 1879

I’ve encountered various references to deplorable political generals and their attendant poor and negligent battlefield leadership, nepotism and pork barrel ethics. It was interesting and informative to read an in-depth account of one of these characters. I appreciate all the primary research you apparently did in writing this.

As a former resident of Lancaster, OH, I find it really interesting that the town arguably produced one of the “worst” generals in Schleich and one of the “best” generals in Sherman. What are the odds?