Voices of the Maryland Campaign: Introduction

In my years of researching and writing about the Maryland Campaign, something about the campaign has always proved an enigma. As anyone interested in the Civil War knows, there are a lot of sources to sift through–just look at any of the compiled bibliography books that are out there. But it seems that every single time I find a new regimental history, set of letters, or whatever of someone or some unit that should be in the Maryland Campaign, they either seem to have missed the campaign due to sickness or, for some unexplained reason, their diaries or letters go blank during the campaign, not resuming again until later on. (One can better imagine than I describe the number of times I have nearly pulled my hair out over this unfortunate circumstance.)

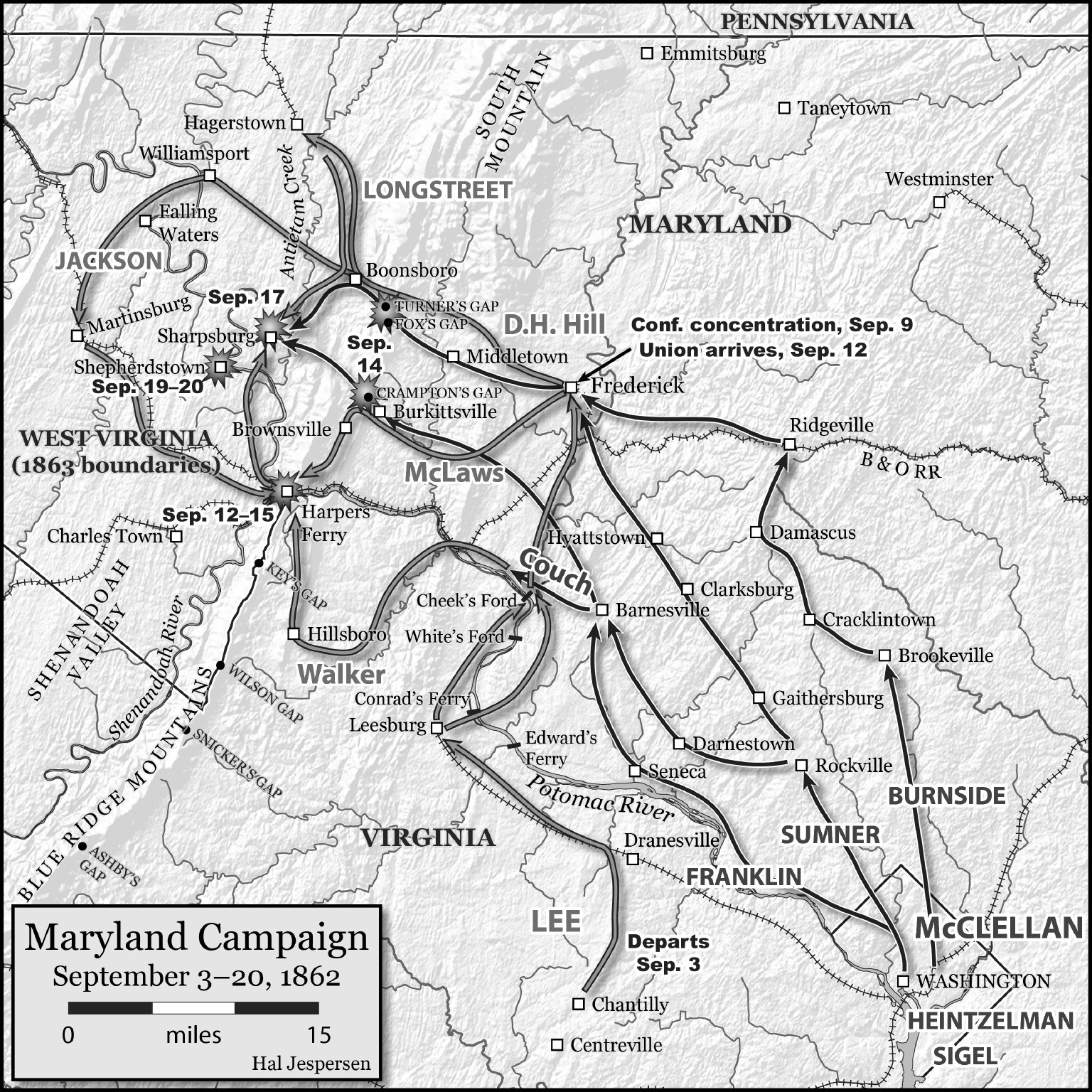

The more I have studied this campaign, however, the reasons for the relative lack of sources has become apparent to me. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862 was fought on the tail end of the war’s first Overland Campaign, with near constant marching and fighting in the war’s Eastern Theater from the end of June to the middle of September. Both armies were worn thin in this campaign. Soldiers pushed to the limits of their endurance melted away on the hot and dusty marches that weaved through the Maryland countryside, leaving the strength of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia depleted. Not to mention the sickness soldiers contracted while serving in swamps of the York-James Peninsula held many on the sidelines for the tromp into the Old Line State.

This ties in nicely with the “blackout” of many diaries and letters during the campaign. Straggling was not the only issue both armies had to deal with, but supplying their men proved difficult, too. I am not talking about just food, clothing, and ammunition, but paper as well. Take Col. Walter Phelps, for example, a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac’s First Corps. On September 18, he penned a letter to his wife on Confederate stationery, noting at the top, “no other paper to write on.”

All of this is to say that despite the disparity in sources, there are still plenty out there (just not as many as I would like). With the fate of both the United States and the Confederate States hanging in the balance in September 1862, the witnesses to the campaign recorded their thoughts, feelings, and whereabouts as best as they could. They knew, from the highest ranking generals to the lowliest private soldier, that the stakes ran high in Maryland. Success for the Confederacy likely meant its independence while defeat for the United States probably signaled its demise. “If we fail now the North has no hope, no safety that I can see,” confided Gen. Alpheus Williams to his daughter.

To commemorate this year’s anniversary of the campaign, 155 years ago, I will be sharing from the letters, diaries, and recollections of the participants each day, from September 2-20. Keep your eyes open on the blog, and join me in remembering the individual participants in one of the nation’s most crucial military campaigns.

I have always found the timidity of McClellan’s ” generalship ” astounding! The piecemeal commitment of his corps in dribs and drabs throughout the battle, his relative isolation from the field, the withholding of strong reserves….as the gallant Phil Kearny implied of McClellan, before his untimely death,( and I paraphrase) ” There is either rank cowardice here, or treason “

McClellan was a great general of administration, organization, and morale. The Army of the Potomac loved him. He was very cautious and that had much to do with his political philosophy on how to fight a civil war. He wanted to treat the rebels gently, to help encourage reunion. He also didn’t want to throw away his mens’ own lives. He didn’t have the killer instinct that Grant, Sherman, and others had, but ultimately he is responsible for killing and mutilating thousands of Confederates, which ultimately helped win the war.

When he committed 9th Corps at 0800 he’d committed every division on the field except Morell’s incoming division to an attack. There is some evidence that McClellan ordered 9th Corps committed earlier (before 0700) but Burnside claimed this order was a warning order. If Sumner hadn’t gotten lost and been found sitting on the steps of Hooker’s old HQ, 2nd Corps would probably have gone in at dawn as McClellan ordered.

6th Corps were committed as soon as they arrived, and eventually even 2 brigades of Morell’s division were committed to the right, but then recalled due to the developing circumstances. The sum total of brigades in McClellan’s reserve is one; Barnes’ brigade of Morell’s division.

The paper issue causes lost data elsewhere. At Glendale and Malvern Hill the signal operators relaying between McClellan and his commanders reported running out of paper and thus not recording what was sent. Hence most (but not all) of the messages are lost to posterity.