Mexican-American War 170th: Battle of Molino del Rey

Winfield Scott’s armistice had failed. His dual victories at Contreras and Churubusco on August 19-20 brought the American army within a hand’s reach of Mexico City, but then Scott stopped. By August 24, Scott and Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna agreed on a ceasefire that kept the armies at bay while negotiators began talks of peace.

Nicholas Trist took up the baton, again opening a dialogue with Santa Anna and other Mexican diplomats. The diplomat kept his talks up for almost a week, but as the days went on, nothing came of the negotiations. Following one day of discussions the Americans reported back to Scott that Santa Anna still “would require. . . that the Nueces [River] should be the boundary” between the two countries. That argument went back to the very beginning of the conflict, and Santa Anna refused to budge on the point. Ethan A. Hitchcock, serving on Scott’s staff, bemoaned in his diary, “No peace can be had.”[1]

Further negotiations began to break down as Santa Anna broke promises of the armistice. Low on food, American wagons were supposed to be allowed into Mexico City to gather provisions from Mexican merchants, but instead the first wagon train into the city had to defend itself from mobs, and Santa Anna refused to allow the sale of goods to additional American parties. And yet, for all his broken promises, the American high command knew they had to deal with Santa Anna; in the midst of Mexico’s volatile political situation, with frequent coups d’états, if Santa Anna was dethroned, the Americans could not know who else would come to power, or if they would be amenable to ending the war. Better the devil you know, the Americans figured, than the one you don’t.

But as the talks continued to go nowhere Trist became despondent, and the American army became restless. A correspondent who had followed Scott’s campaign, George W. Kendell, wrote that the armistice “has produced universal dissatisfaction in the army—the entire army.” Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant added, “Is it ended, or will hostilities be resumed? We are prepared for either event.”[2]

Scott’s forces would have to be prepared, because on September 6 he cancelled the armistice, giving the Mexicans a 48-hour notice, telling them the war would resume on September 8. The last straw came when Scott found out that, during a time when there was supposed to be a ceasefire, Santa Anna was using the truce to strengthen his defenses, outfit more soldiers, and prepare defenses. Furthermore, rumors came to Scott’s ears that Santa Anna was using an old mill as a cannon foundry, melting down Mexico’s church bells into artillery tubes. That mill, called Molino del Rey (King’s Mill), became Scott’s target with the resumption of fighting on September 8 as he “resolved at once to drive [the Mexicans] early the next morning, to seize the powder, and to destroy the foundery.”[3]

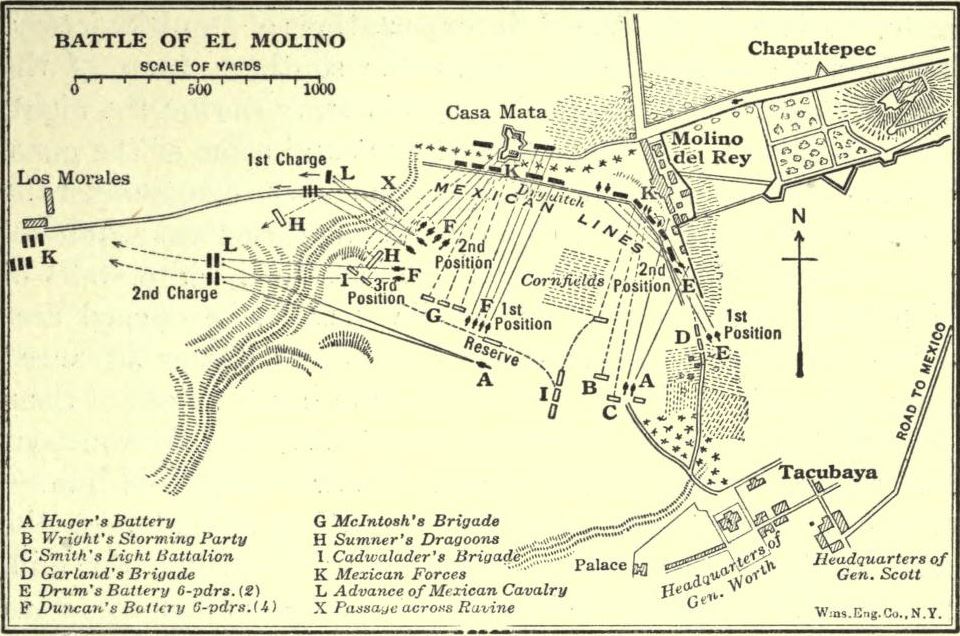

Scott turned to Maj. Gen. William Worth to lead his division against the mill. Within 1,000 yards of the mill was the castle Chapultepec, a fortress that protected the approaches to Mexico City. Worth’s orders were to take Molino del Rey, but not get sucked into a vortex against Chapultepec, because at that time Scott thought “we might altogether neglect the castle,” if he could find a way around it.[4]

Worth’s men woke early on September 8, and, in the words of Capt. Robert Anderson, left their camps “about half-past two A.M.” The Americans advanced in the darkness to the outskirts of the mill, and waited for sunrise to launch their attack. Worth’s two brigades would be supplemented by other brigades that Scott forwarded from Gideon Pillow’s and David Twiggs’s divisions.[5]

Bringing artillery up, the Americans opened fire when it was “quite dark,” bombarding the mill’s structures but not doing much damage, leaving historian K. Jack Bauer to refer to the opening salvo as “skimpy.” [6]Once the American artillery stopped firing, Worth’s men charged the mill’s walls. Molino del Rey consisted of a “a range of buildings. . . five hundred yards long. . . constructed of massive stone, and within has various subdivisions or yards,” remembered an American officer.[7] Next to the mill complex a fort called Casa Mata protected the causeway leading to Molino del Rey. Huddled inside the strong fortifications of the mill and Casa Mata, the complex’s Mexican defenders waited for Worth’s men to get closer. As the Americans neared the mill’s front entrance, the Mexicans finally opened fire with a blistering volley of musketry, “literally cutting our troops to pieces,” wrote D.H. Hill.[8] Worth’s leading men reeled back from the intensity of the blast, taking cover wherever they could. Mexican counter-attacks drove the Americans further away from the mill.

The heavy Mexican fire continued to take its toll. Advancing against the mill and engaging the Mexican defenders, the 4th U.S. Infantry lost 11 of its 14 officers. Further down the line, the 6th U.S. Infantry also took heavy casualties, leaving the young lieutenant Winfield S. Hancock in command of a company. In the 5th U.S. Infantry, Capt. Ephraim Kirby Smith went down with a mortal wound, dying three days later; his younger brother Edmund would go on to become a Confederate general. Trying to get help for their infantry, American gunners attempted to bring cannon closer to blast down the mill’s doors. Captain Robert Anderson in the 3rd U.S. Artillery sprinted out and was struck in the shoulder by a spent ball. Recovering, he kept advancing until within an entryway of the mill, when a second bullet “grazed my right leg,” and he soon retreated to the rear in a daze.[9]

As Worth deployed more men, and as Scott hurried reinforcements from Pillow’s and Twiggs’s divisions, the Americans began to make headway. They got into the mill, and locked bayonets with the Mexican defenders, gradually driving them out and closer to Chapultepec. Mexican reinforcements started to come out of the fortress east of Molino del Rey, but were driven back by riflemen, some under the command of Joseph Johnston.[10] The American artillery managed to convince other Mexican commanders that an attack out of Chapultepec was not worth the cost it would bring.[11]

The fighting for the mill lasted about two hours before the surviving Mexican forces retreated towards Chapultepec. Casa Mata soon also fell and then explode in grand fashion as fires starting during the battle got to the small fort’s powder magazine. It had cost Scott’s men heavily: 116 Americans were killed and another 665 wounded. They had captured Molino del Rey, but in searching the mill’s buildings, found that it had been a wasted effort.

Scott had planned the entire operation to secure what he had been told was a cannon foundry, but in searching, Americans only found “some cannon molds, but no cannon and no cannon production.” To many battered and bloodied American soldiers, the whole battle had been for nothing, with D.H. Hill writing that General Worth had been “deceived” by the rumors of a cannon foundry.[12] Ethan A. Hitchcock wrote in his diary, “a few more such victories and this army would be destroyed.”[13]

While Molino del Rey left a sour taste in many an American mouth, Winfield Scott looked for what came next. There would be no more armistices, no more truces, or ceasefires. His army was within five miles of Mexico City, and Scott aimed to finish what he had started back on the beaches of Vera Cruz. The grand climax of the Mexico City Campaign was at hand.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Fifty Years in Camp and Field: Diary of Major General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, U.S.A. Edited by W.A. Croffut. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), 289.

[2] George W. Kendell, “Relative to the Armistice,” Niles’ National Register, September 18, 1847; The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 01: 1837-1861, Edited by John Y. Simon, Southern Illinois University Press, 144.

[3] Winfield Scott, Memoirs of Lieut.-General Scott (New York: Sheldon & Company Publishers, 1864), 505

[4] Ibid., 506.

[5] Robert Anderson, An Artillery Officer in the Mexican War: 1846-7 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1911), 311.

[6] George H. Gordon, “Battles of Molino Del Rey and Chapultepec” in Civil War and Mexican Wars, 1861, 1846, (Boston: Papers of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Volume 13, 1913), 608; K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974), 309.

[7] Gordon, 605.

[8] Daniel Harvey Hill, A Fighter from Way Back: The Mexican War Diary of Lt. Daniel Harvey Hill, 4th Artillery, USA, ed. Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and Timothy D. Johnson (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2002), 122.

[9] Anderson, 313.

[10] Scott, 506-507.

[11] Bauer, 311.

[12] Timothy D. Johnson, A Gallant Little Army: The Mexico City Campaign (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 208.

[13] Hitchcock, 298.

American generals are often categorized as either Ikes or Macs.

Taylor, Grant and Eisenhower are in the former for being down to earth populists that are more likely to become president.

Scott, McClellan and MacArthur are in the later for being elitist snobs that would be more appreciated in Britain.

Curious to know your opinion about this cultural generalization. Especially with regards to whether being called ‘Rough and Ready’ is preferable to being called ‘Fuss and Feathers.’

– Will Reardon

Hi Will, that’s a really great question.

I’ve written a few times during my Mexican War series that I believe Winfield Scott was probably the greatest American soldier of the 19th century. That’s good and bad for him- good for the fame it wins him, but bad because of the larger societal bias against a standing American army. In that regard it is definitely helpful to have the allure of Rough and Ready Zachary Taylor– the easygoing, down to earth general who was sometimes mistaken by a private by newcomers because of his ways and habits of not always wearing a general’s coat. Such a notion would be absurd to Winfield Scott.

Scott lost the 1852 election to Franklin Pierce, which is significant to our studies because Pierce was a subordinate to Scott during the Mexican War. But Scott had devoted his career to being a soldier, whereas Pierce had only served as a volunteer until the war was over, which again, fit the mold of the public opinion of what an army should be: raised by citizens, who fought the war and then disbanded and went back to being citizens.