Battlefield Markers and Monuments: “To the Workingmen of Manchester”

There was a moment when America’s Civil War resonated across the Atlantic, creating a significant, but momentary impact on the British working class…and creating a monument.

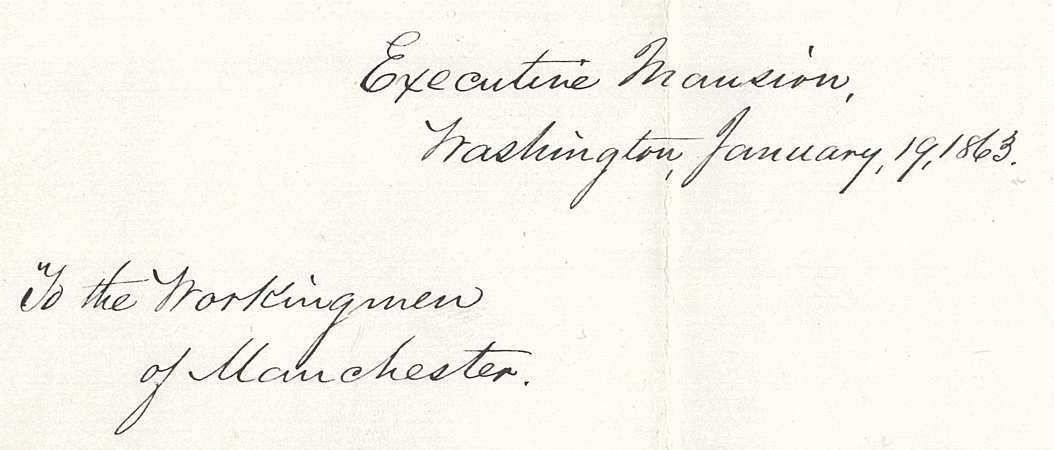

“I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working-men of Manchester, and in all Europe, are called to endure in this crisis,” penned President Abraham Lincoln on January 19, 1863 in a letter addressed to the struggling masses of that northern stronghold of British industry.

Lincoln was responding to an address given at a meeting for the Workingmen of Manchester, held at the Free Trade Hall in December 1862, which offered support to the Union’s struggle in the ongoing Civil War.

Furthermore, the address urged the emancipation of all African American enslaved people, regardless of the distress it would cause in both the U.S., and in those industrial centres across Europe which relied heavily on southern cotton.

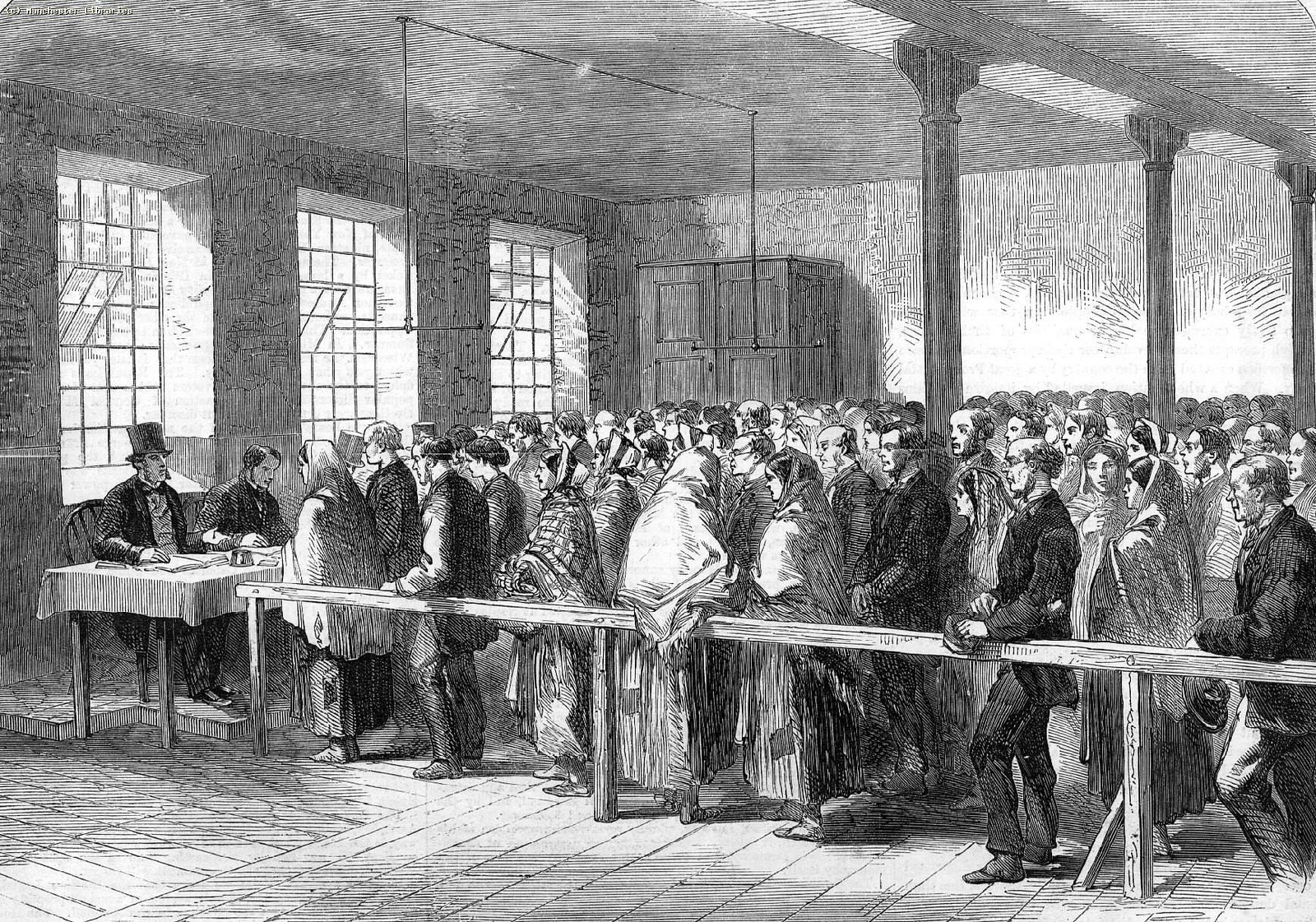

In an exhibition of self-sacrifice, the working-classes of Manchester put universal freedom ahead of their own economic self-interest during the detrimental Lancashire Cotton Famine.

They understood the Civil War not as some territorial or economic dispute confined to the United States, but as a universal struggle for human rights played out on an American stage.

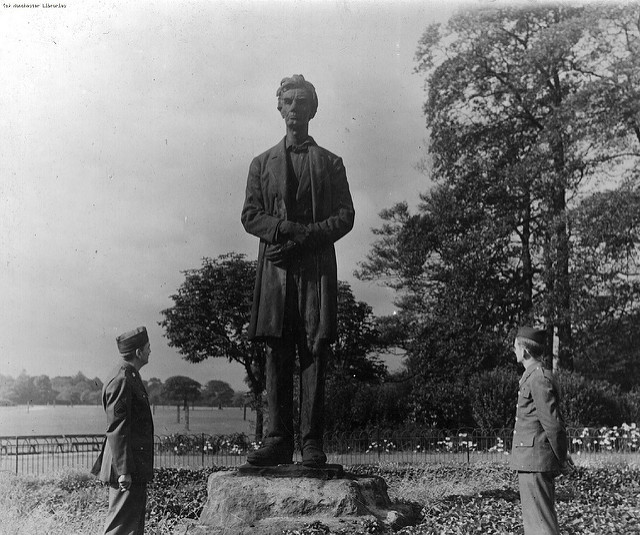

Manchester’s Lincoln is a unique immortalisation of the American president, and not because it doesn’t reside in the United States. Three statues of Lincoln exist in the United Kingdom: in London’s Parliament Square he stands statesmanlike and pensive, whilst in Edinburgh’s Old Calton Cemetery he towers over an unshackled slave.

Manchester’s Lincoln, however, sculpted by the American George Grey Barnard, was considered by some observers as “gloriously ugly,” “touchingly pathetic,” and “awkward… ill-proportioned and disfigured.”

Others recognised a humble figure, and noted the memorialisation to be representative of “the ethos of progressive democracy,” and the “embodiment of a great but as yet in many ways uncultivated democracy.” I find myself in the latter camp.

The debate over this representation of Lincoln is part of of the reason it is present in Manchester today. Originally intended to stand in London, it was deemed inappropriate for the capital, not statesmanlike enough, and was left without a home.

Manchester claimed the statue in 1918, owing to its connections with Lincoln during the Civil War. Though not all those working in the British cotton industry were sympathetic to the Union’s cause, it was an attempt to express the liberal values of Manchester. When Manchester obtained the statue, this poorly-received representation’s meaning was transformed.

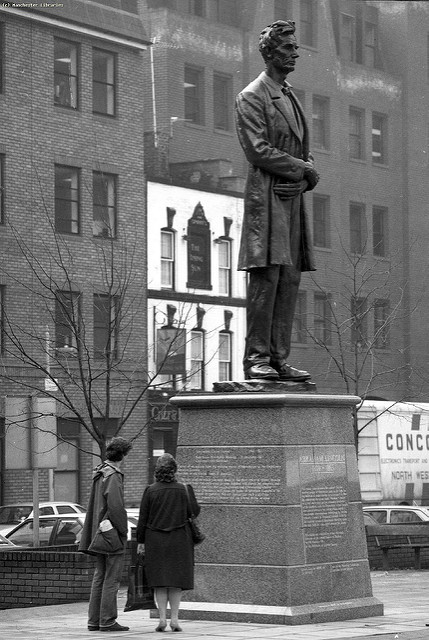

However, the Manchester Lincoln statue’s reputation remains as unpretentious as its aesthetics, and few are aware of this monument to emancipation, working-class solidarity, and Anglo-American ties.

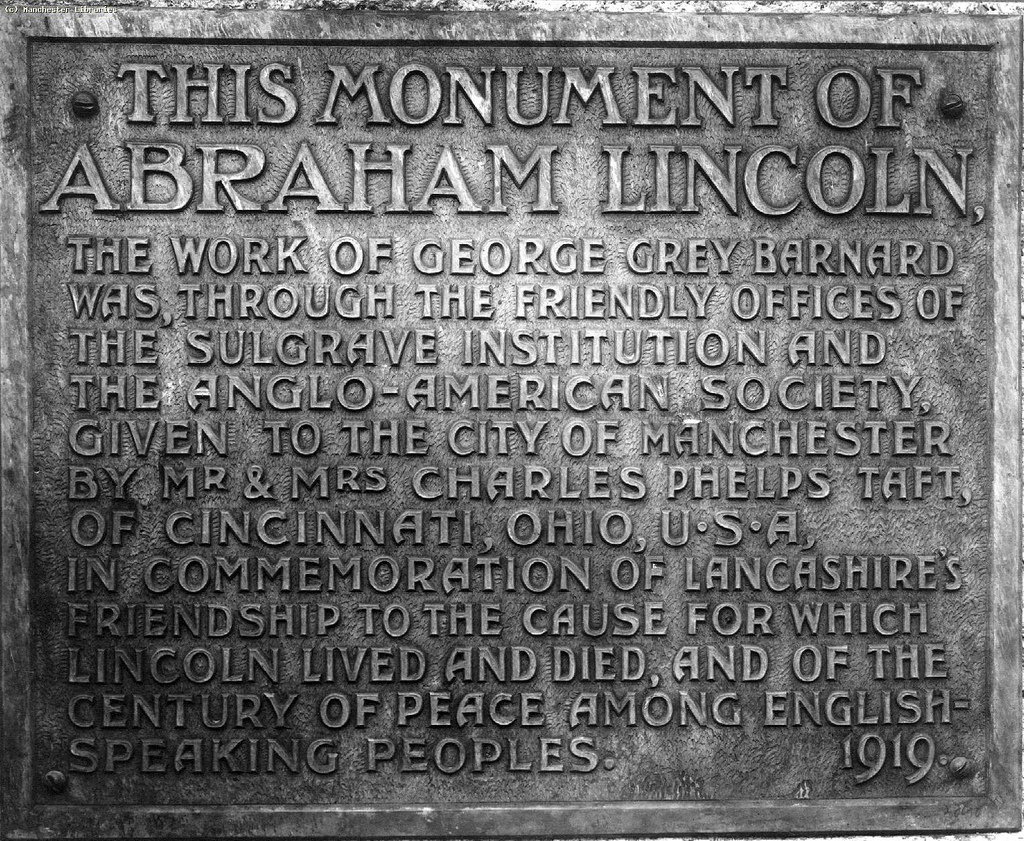

In 2007, when the United Kingdom marked the 200th anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, it was deemed “shameful” that the statue had been allowed to suffer the ravages of pollution and the weather. It was almost impossible to read the plaque that detailed the special relationship between Lincoln and Mancunians. Restoration work was carried out.

Manchester’s Abraham Lincoln Statue might seem as remote as can be from a Civil War battlefield marker. Over 3,000 miles distant from the seat of the war, it stands on a busy street in a British industrial city.

But the statue’s history reveals a conflict fought over its meaning, and whether it was even fit to represent the American president abroad. When Mancunians claimed the statue in 1918, they imbued it with an oft-neglected story of the Civil War: a story of a smaller battle, one that was physically distant but nevertheless ideologically bound to the great conflict waged in the warring United States.

Statues such as Manchester’s Abraham Lincoln, regardless of their flaws, are powerful reminders of the great reverberations that the United States’ internal conflict sent around the world. And it wasn’t only in the parliaments and monarchical courts of Europe that the war was recognised as a great contest between liberalism and reaction, but in its streets, and in the homes and assemblies of its most ordinary individuals.