Struck by a Fired Ramrod, Part 2: Mysterious Death and Elaborate Funeral

This is part two of a three-part series. Part one can be found here.

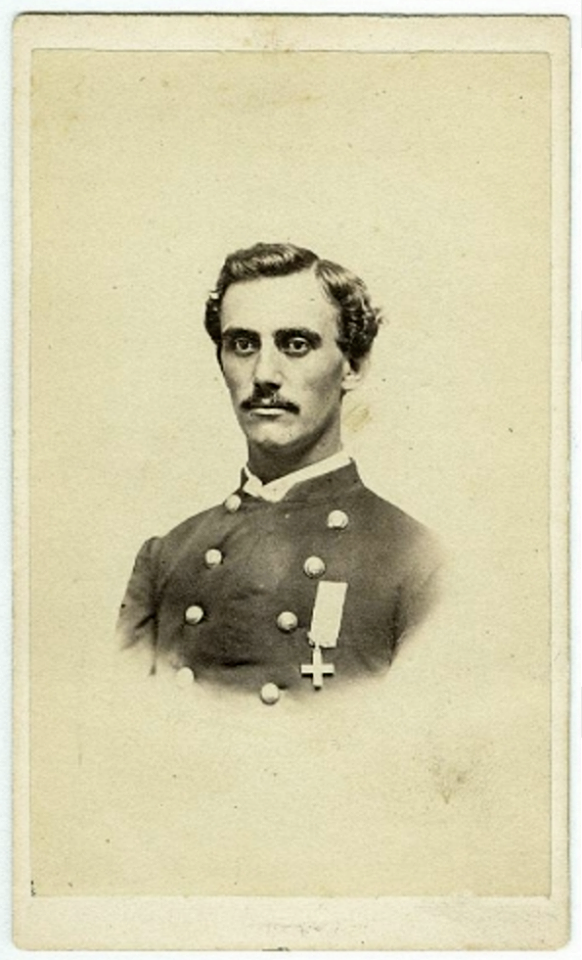

Major William Ellis returned to the Army of the Potomac near Petersburg in mid-June. He knowingly cut short his recovery from a gruesome wound received from a Rebel who fired a ramrod at the 49th New York Infantry’s second-in-command at the Bloody Angle on May 12, 1864. Upon arrival to Petersburg he was detailed as inspector general on David Russell’s staff. In early July his new division, as well as the VI Corps’ second division, sailed for the national capital. There they beat back the Confederate invasion at Fort Stevens, during which battle Lt. Col. George W. Johnson, commanding the 49th, was mortally wounded.

For a short time the VI Corps chased Early through Maryland before settling into place near the Monocacy battlefield. There they enjoyed their break from combat, trenches, and southern soil. “All are well in the regiment,” wrote Surgeon George T. Stevens. “We have a lovely situation here among the mountains, with the purist of air and of water, and if we can only stay here, we shall recruit [recover, recuperate] wonderfully. I am feeling a great deal better already, & expect to be as strong & well as ever in a day or two.”[1]

Adjutant Theodore Frelinghuysen Vaill recalled that the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery “encamped on the 3d of August on the north bank of the Monocacy, about four miles south of Frederick City. It was the pleasantest camping ground we had ever seen. The clear, sparkling river ran along the lower edge of it, and the surrounding woods abounded in saplings, poles and brush, for which soldiers can always find so many uses. Regular camp drills were instituted, company and battalion drills ordered, and things began to assume the appearance of a stay.”[2]

Major Ellis retired to his tent on the night of August 3rd, telling Stevens, the surgeon recalled, that his “pain was slightly more acute than usual” though he was “in his accustomed health.” The next morning Ellis waved his servant out of the tent for a moment and when the man returned he was shocked to find the major dead.[3]

Ellis’s unexpected passing was immediately misdiagnosed by most. “They supposed it must be heart disease,” wrote Capt. Mason Tyler. Rumors quickly spread through the Union camps. Sergeant Cyrille Fountain chronicled in his diary, “This morning Major Elles of the 49th N.Y. Vols dropt down dead from his char. The Drs. called it hart desease.” The first Buffalo newspaper to report the death meanwhile assumed “it is supposed that he was killed in an effort to drive the rebels out of Maryland.”[4]

Upon hearing the news Stevens and Dr. James Hall proceeded immediately to Russell’s headquarters where the general insisted on an immediate autopsy. In the presence of twenty of his professional colleagues, Stevens examined the body and found that lingering effects of the Spotsylvania wound had killed Ellis, concluding, “A sharp splinter of bone from one of the ribs was found with its acute point piercing vital organs.”[5]

Stevens further described his findings in his letter to his wife, “I made the examination and found that the ramrod had split a splinter of bone from one of the ribs, and that splinter, as sharp as a needle, had been piercing & irritating the internal organs ever since he was wounded. Abscesses had formed & broken in the spleen & the diaphragm had been haggled through, and finally the splinter had pierced the lung & had killed him instantly.” The surgeon preserved parts of the rib and diaphragm for medical study and noted Ellis’s physical toughness, “It is wonderful that during the month he had been on duty he had made no complaint of pain, although his countenance showed constant suffering.”[6]

Like the misinformed rumors of heart disease had earlier, the full coroner’s report now evidently spread through the ranks with remarkable speed and detail. Corporal John F.L. Hartwell, 121st New York, wrote a detailed summary the next day to his wife. “He was shot with a ramrod which shattered a rib, a piece of the bone could not be extracted & it remained loose on the inside. Yesterday morning this bone in contact with his liver or heart & caused almost immediate death, his body was sent immediately north.”[7]

While the medical professionals examined the corpse, Russell set his own staff to work in preparing an elaborate funeral procession. The entire 1st Division turned out as the fallen officer’s remains were carried to a train bound for New York. “It was the most impressive and grand pageant that I ever witnessed,” recalled Stevens. “I have often seen military displays on a far larger scale, but nothing to compare with its solemn sublimity.”[8]

Ellis’s body was wrapped in a silken flag and laid in state next to Russell’s headquarters in a large tent draped with the Stars and Stripes. The 49th New York marched past, unarmed, as mourners and formed next to the tent in two ranks facing each other. Chaplain Winthrop Henry Phelps, 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery, offered a brief sermon, deemed “very appropriate and impressive” by Stevens.[9]

All of Russell’s division meanwhile formed in two parallel lines of battle, eighty paces part and facing each other, with, according to various sources, either a heavy artillery regiment or four companies of the 121st New York detailed as an escort. When Phelps concluded his sermon, Ellis’s remains were “inclosed in a rude coffin, wrapped in the flag under which he had so often fought,” and placed in an ambulance draped with a flag and the major’s hat, coat, and sword. With a mournful dirge providing the solemn musical accompaniment, the ambulance passed in front of its escort who stood at present arms. The escort then reversed their arms and marched slowly in front of the ambulance, which was followed in turn by Ellis’s horse, saddled and bridled, but riderless. The band followed, still playing their dirge.[10]

Slowly the large procession passed through the sunbrowned ranks of the division, twin lines stretching a third of a mile, where all stood at present arms with uncovered heads. Each regiment lowered their colors in honor as the ambulance passed. The 49th New York fell into line behind the ambulance, followed by Russell, his division staff, and those of the various brigades, all bearing their own flags. “A large concourse of officers, personal friends of him whose remains were thus honored,” accompanied the procession, as did many from the 2nd Division to which the 49th belonged. After passing down the length of the line the column sped up its pace and marched three miles to the train station at Buckeyestown. After a short service the coffin was loaded on the cars bound for Baltimore, then Buffalo.[11]

In his letter that day, Stevens supposed “that friends at home would hardly think that firearms, military parade, bands of music, & muffled drums were best calculated to produce solemnity on a funeral occasion, but I can not conceive a more deeply solemn show than that which we have witnessed this morning. Indeed, it seems to me that for any grand display in which an impression is to be produced, whether for the brilliant gayeties of a Fourth of July, or the mournful rites of a funeral, nothing can compare with a military parade.”[12]

A newspaper correspondent meanwhile observed, “The funeral service was one of the most imposing ever witnessed in the Army of the Potomac… Major Ellis was one of the most popular men in the corps. He was beloved by both officers and men, to whom he had endeared himself by his unassuming demeanour and great bravery. To his immediate associates his loss is irrepairable, by whom, together with his numberless friends in the Sixth corps, his death will long be regretted.”[13]

Captain Elisha Hunt Rhodes, whose writings are popularly consulted by modern historians, simply noted, “Major Ellis, a Division staff officer, died yesterday from the effects of wounds received at Spottsylvania. The entire Division was under arms and saluted the remains as they were bourne past our lines.”[14]

Many of the soldiers also participated in special religious services that day as part of a proclamation by President Lincoln calling for a Day of National Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer. “Attended in an open field where the sun was hot enough to melt almost anything down,” wrote Corporal John Hartwell. He expressed resentment toward the special treatment for the officer. “A great parade was made over him, more than would have been shown a whole brigade of private soldiers if all died at once.”[15]

Others deemed such displays appropriate, given the major’s reputation. “Such men deserve the honor which our heroic people are ever willing to aware to merit and patriotism,” stated the Buffalo Advocate. “Thus our brave men go forth, gallant in spirit, fired with the best and loftiest inspirations to fight and die for their native land.”[16]

With the benefit of hindsight after the war, Adjt. Vaill realized the elaborate display represented more than just the loss of Ellis. The military parade occurred during a time of respite “after so many officers men had been buried without funeral, coffin, shroud, or audible word of prayer.”[17]

Perhaps, indeed, the funeral was the first real opportunity to take time to reflect on the massive amount of blood shed within the VI Corps over the last three months—at the intersection of the Brock Road and Orange Plank Road as well as during Gordon’s flank attack at the Wilderness; during Upton’s assault and at the Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania; the June 1st attack at Cold Harbor, Vaill’s Connecticut regiment’s first trial by fire; their brief stay in the Petersburg trenches and the wholesale capture of several Vermont regiments abandoned without support at the Weldon Railroad; the desperate struggle to delay the Confederate invasion at Frederick City; the unnerving test protecting the national capital under the eyes of the president.

Along the tranquil banks of the Monocacy River the VI Corps at last exhaled. The coffin that passed through their ranks on August 4th did not just carry Ellis’s body but that of thousands of brothers-in-arms whose lives had been lost without time enough to properly mourn.

Even the body of the beloved Uncle John Sedgwick was unable to receive as proper of a send-off after the major general’s death at the hands of a Confederate sharpshooter on May 9th. Just twenty-four hours later, one-third of the corps was tasked under Upton to carry out one of their most dangerous assignments of the war.

Sergeant Alexander H. McKelvy detailed the 49th New York’s casualties during their first eight days of the Overland campaign, “During this week of fighting at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, the regiment lost 231 in killed and wounded out of the 384 officers and men who crossed the Rapidan on May 5th. Of his number, 89 were killed or mortally wounded. Ten officers were killed and four wounded.” William F. Fox wrote in his Regimental Losses in the Civil War, “At Spotsylvania the [49th] regiment behaved with especial gallantry, its percentage of loss in that battle being a remarkable one.”[18]

Within days of Ellis’s death, Phil Sheridan would arrive to guide the VI Corps and the newly organized Army of the Shenandoah into its namesake region in an incredibly successful campaign. The terms of service for the 49th expired on September 17th, but four consolidated companies of reenlisted New Yorkers composed a battalion that continued through the end of the war. They joined Sheridan for his victories in the valley that nevertheless further deplete the leadership in Wright’s command. Emory Upton would be wounded and David Russell killed on September 19 at Third Winchester. A large battle one month later at Cedar Creek would claim the life of the 49th’s first commander, Daniel Bidwell, now leading the brigade. The corps rejoined the Army of the Potomac at Petersburg in December and played an important role in the final campaign. One week before Confederate surrender at Appomattox, Lt. Col. Erastus D. Holt, in charge of 49th, was also mortally wounded, though, shot by a Confederate picket while the corps formed overnight for their decisive charge on April 2nd. “The Forty-ninth suffered a severe and unusual loss in the number of its field officers,” noted Fox.[19]

The 49th New York’s adjutant, 1st Lt. John P. Einsfeld, meanwhile in August 1864, accompanied Ellis’s body to Buffalo. Upon arrival, eight members of the Veteran Reserve Corps escorted the remains from the Erie Railway station to Catharine Ellis’s home. Funeral services were held on Thursday, August 11, at the Church of the Ascension. The Buffalo Daily Courier eulogized the fallen:

In the death of Major Ellis, the country has lost one of the noblest of its defenders. All who knew him concur in eulogy of the chivalry, the lofty patriotism, the noble manliness which marked his character. He was indeed a good and true knight, sans peur et sans reproche [without fear and without reproach]; as tender and faithful in his discharge of duty as a son and brother as in his military capacity he was brave and soldierly. At one of the battles of the Wilderness he was shot through the arm with the ramrod of some rebel soldier’s gun, the strange missile at the same time inflicting a severe blow on his side near the heart. He came home on a furlough, but, anxious to be with his regiment, returned to the field before he had fairly recovered. In the absence from the regiment of both Col. Bidwell and Lieut. Col. Johnson, the command of the 49th devolved upon him, and it is believed that over exertion in front of Washington gave a fatal character to the stroke received near his heart. “For such choice souls earth has no price, no mart.”[20]

Company D of the 74th New York Infantry escorted the major’s body to Forest Lawn Cemetery where it was finally laid to rest. “A braver, purer heart has not been laid beneath the Lawn’s green sod.”[21]

This is part two of a three-part series. Part one can be read here. Part three will be published tomorrow.

[1] Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[2] Theodore F. Vaill, History of the Second Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery. Originally the Nineteenth Connecticut Vols. (Winsted, CT: Winsted Printing Company, 1868), 89-90.

[3] Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps, 385.

[4] Mason W. Tyler to parents, August 4, 1864, Tyler, Recollections of the Civil War, 262. Cyrille Fountain, Diary, August 4, 1864, Donald Chipman, ed. “An Essex County Soldier in the Civil War: The Diary of Cyrille Fountain.” New York History (July, 1985), 303. “Death of Major Ellis,” Buffalo Daily Courier, August 6, 1864.

[5] Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps, 386.

[6] Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[7] John F.L. Hartwell to “My Dear Wife,” August 5, 1864, Ann Hartwell Britton and Thomas J. Reed, eds. To My Beloved Wife and Boy at Home: The Letters and Diaries of Orderly Sergeant John F.L. Hartwell (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997), 266.

[8] Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[9] Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[10] Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps, 387.

[11] Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps, 386-387.

[12] Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[13] “The Late Major Ellis,” unidentified newpaper article, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.

[14] Robert Hunt Rhodes, ed. All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes (New York: Vintage Civil War Library, 1992), 169.

[15] John F.L. Hartwell to “My Dear Wife,” August 5, 1864, Britton and Reed, To My Beloved Wife and Boy at Home, 266.

[16] “Honor to the Brave Dead,” Buffalo Advocate, August 11, 1864.

[17] Vaill, History of the Second Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery, 90.

[18] McKelvy, “Forty-ninth New York Volunteers,” 390. William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1865-1865 (Albany, NY: Albany Publishing Company, 1889), 197.

[19] Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 197.

[20] “The Late Major Ellis,” Buffalo Daily Courier, August 9, 1864.

[21] “Funeral of Major Ellis,” Buffalo Daily Courier, August 13, 1864.

1 Response to Struck by a Fired Ramrod, Part 2: Mysterious Death and Elaborate Funeral