A Commemoration to Remember Dranesville

I’ve been to my fair share of battle commemorations. I’ve listened to “Taps” every half hour while working at a National Cemetery’s Memorial Day service. I’ve laid carnations at Fredericksburg’s famous stone wall. But just a little while ago, I went to one of the most unique, touching, and well-done observances of a battle’s anniversary.

It was for the battle of Dranesville, fought Dec. 20, 1861. The Union victory there left about 50 dead, and another 260 wounded. It was a small battle, only a brigade’s worth of troops on both sides, but the dead and wounded left their mark on the landscape. In 1861 there was a strip of land owned by John Rowzee where the 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery unlimbered. By 1912, that strip of land had become home to the Dranesville Church of the Brethren. A Christian denomination with a core tenet of pacifism, the Brethren hold a commemoration every year in their sanctuary so that the dead and suffering of Dranesville are never forgotten. That is a risk, too, without the program—the entirety of the battlefield is all but gone under asphalt and split highways. Because of my recent research into the battle, I had had the event on my calendar for almost a year, and made my way to their program.

I’m not an overly religious person, and I don’t make a habit of going to church on Sunday. But I arrived in Dranesville and was swept up by the serenity of the moment. Up near the altar were 50 candles, each flickering in memory of a life ended outside. Where, in 1861, the “balls flew so thick that the pines fell like rain,” now the congregation sat in quiet reflection. At the end of a quick sermon about peace and readings about the beginning of the war, a few hymns were sung. The finale to these was “Amazing Grace”, and the memories of these soldiers came flooding into the sanctuary. With the end of the song, the lights to the sanctuary were turned off, descending the congregation into a near a total darkness—except for the 50 candles ahead of us. Those candles were our guiding light. And then they started to go out as names were read.

“Sixth South Carolina Infantry, Killed in Action.”

“Obadiah Harden.” Elected as captain of Company E, Harden fell wounded in front of his men on December 20. His wound festered, turned to tetanus, and he died New Year’s Day, 1862. He was immediately followed by,

“Thomas Harden.” Obadiah’s younger brother died as the Carolinians pushed towards the Leesburg Pike, running into the 6th and 9th Pennsylvania Reserves. Both Harden brothers were brought back to Chester County, South Carolina.

It got darker.

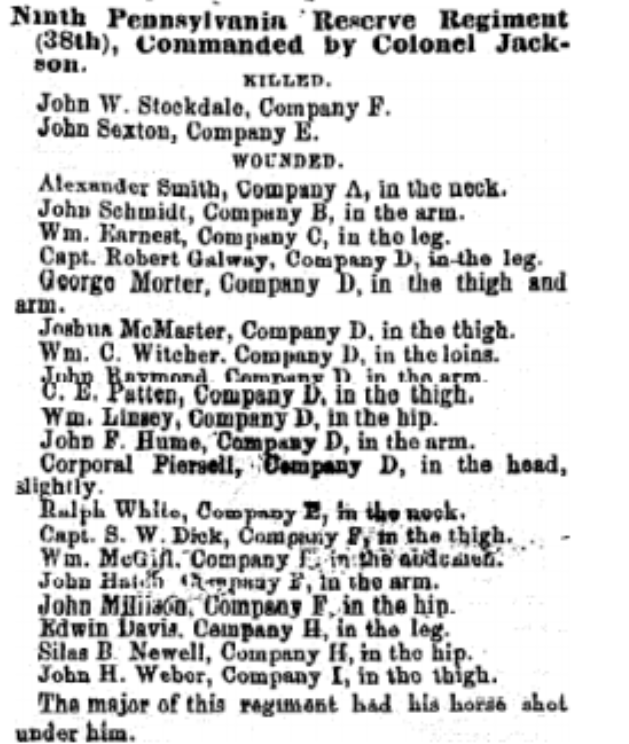

“9th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry.”

“Alexander B. Smith.” The 22-year old Smith had worked in coal before the war, and was among the first Federals hit at Dranesville. Moments before his skirmishing company deployed Smith stood alongside a fellow soldier and traded salt pork for corned beef. They shared a quick smoke, and then rushed headlong into the thick pines in front of them. As the skirmishers fell back from the point of contact, Smith fell, shot in the neck. He was brought back to camp the following day and died of his wounds on January 14.

“11th Virginia Infantry, Killed in Action.”

“John Henry.” Here was an example of a new generation at war. These were not experienced veterans engaged in pitched battle, but rather, new soldiers seeing serious combat for the first time. In loading his musket, something went wrong, and Henry ended up shooting himself through the bottom of the chin. The bullet passed through his brain and the young Lynchburg resident was likely dead by the time his body hit the ground.

The candles kept going out, and it got darker. Until the end, with just one small flame left. At the speaker’s podium the presenter held the candle, giving just enough to read from the page. But as the last name rang out over the pews the speaker leaned down and blew out the flame. We were left in the total darkness, and it was over. In lieu of a discussion about what either side should have done tactically, the names alone carried the weight of the commemoration.

In a way, it all worked better that way. Because to people like Elizabeth Galbraith, it didn’t matter what flank rested where. In her early 30s, Elizabeth was the mother of two young children when her husband Samuel, fighting with the famed Bucktails, died at Dranesville. A little less than two years later, Elizabeth filed for a government pension, and not even knowing how to sign her own name, drew an X for the registrant. The government gave $12 a month for herself and her two children.

These are the stories of Dranesville, and with the help of the Brethren, they’ll be remembered.

I’m reminded of the line that a small skirmish isn’t small to those who were killed in it. Thanks for paying tribute.

Thanks Chris, absolutely right.

Ryan – what a beautiful ceremony and a beautifully written piece to commemorate it. Great effort. Thank you.

Jack

Hey Jack, thank you very much.

A beautiful and respected way to all ways remember . Not at all like the two confederate monuments to add to the growing list of being tore down in spite of majority feelings .Send away to an unidentified location .SHAME on you memphis .spelled with out a capitol on purpose

My Great Grand Father was a member of that Regt. That was his first Battle

Thank you for remembering these men

Has anyone seen Dranesville spelled “Drainsville”? I have an old map of the battle with the 2d spelling.

Hi William.

Yes, that was a common mis-spelling of the town. I’ve also seen Drainesville, and even occasionally Draynesville. The town was named for Washington Drane in the early 19th century.

Thanks, Best wishes for Holidays. Stay safe.